Case Presentation:

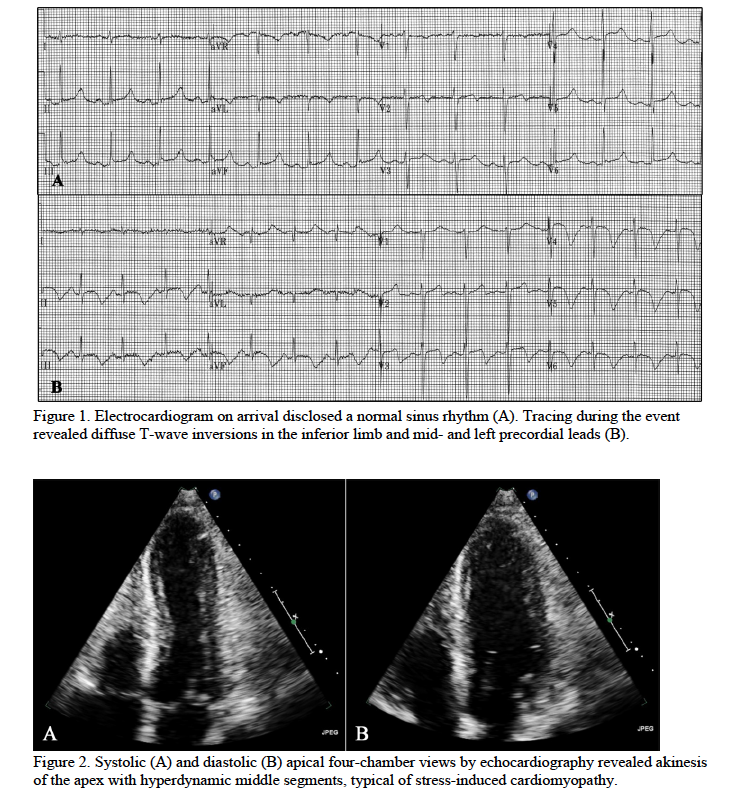

A 53-year-old man presented with a new-onset seizure. The patient recently quit drinking because his wife would no longer give him money to pay for alcohol. He was treated for acute alcohol withdrawal with benzodiazepines and exhibited a waxing-and-waning mental status during the initial three days of treatment. On hospital course day four, the patient developed hypotension and tachycardia. Electrocardiography disclosed deep coving T waves in the inferior limb and mid- and left chest leads (Figure 1). Global akinesis of the left ventricular apex was identified by echocardiogram (Figure 2). Stress-induced cardiomyopathy was suspected. Cautious doses of dexmedetomidine, an alpha-2-agonist, were used to reduce central sympathetic outflow.

Discussion:

Acute alcohol withdrawal is commonly encountered by hospitalists. Autonomic instability is a hallmark of the withdrawal syndrome, and is particularly marked in delirium tremens. Unopposed catecholamine activation and decreased central inhibition can persist for 48-96 hours and can have deleterious effects on the heart. These effects include coronary vasospasm, basal myocardial hypercontractility with subsequent wall stress of the apex, and changes at the molecular level of beta-adrenergic cardiac receptors. It is essential for the hospitalist to recognize severe autonomic instability, such as that which occurs with acute alcohol withdrawal, as a set-up for stress-induced cardiomyopathy.

Due to its similarity with the acute coronary syndrome, hospitalists should be aware of the distinctive clinical features of stress-induced cardiomyopathy. First, the patient’s history likely will indicate an environmental stressor such as acute alcohol withdrawal, severe emotional disturbance, or admission to the intensive care unit. Electrocardiography typically reveals diffuse ST segment elevation or depression and T wave inversion not confined to a particular lead distribution. A key finding by echocardiography is apical wall motion abnormalities that extend over multiple vascular territories. Chest pain, dyspnea, and symptoms such as abdominal pain, myalgia, palpitations, and syncope prevail but are less specific. The syndrome may present in the form of heart failure with acute pulmonary edema or cardiogenic shock, and cardiac troponins may be elevated.

In the management of stress-induced cardiomyopathy, it is important to treat the underlying trigger and to recognize the condition, to avoid treatment with deleterious medications. Agents used in the treatment of ischemic heart disease such as nitrates, statins, and clopidogrel do not provide benefit to patients with stress-induced cardiomyopathy and could give rise to adverse effects. Left ventricular outflow obstruction can be treated with beta blockers, alpha-adrenergic agents, and volume expansion. Calcium channel blockers can be used to decrease the outflow gradient. There is no evidence to support the use of chronic pharmacologic treatment; however ongoing studies are investigating the effects of estradiol, ranolazine, and beta-blockers for long-term treatment. Normalization of apical wall function and resolution of electrocardiographic changes usually takes place within three weeks to a year.

Conclusions:

Alcohol withdrawal is a potential trigger of stress-induced cardiomyopathy. Understanding the pathophysiology of this syndrome including key findings on echocardiogram allows the hospitalist to make an apt diagnosis and administer the appropriate treatment.