Background: UNC’s hospitalist service admits on average 9 patients per week with alcohol use disorder (AUD). UNC does not have a standardized inpatient screening tool for assessing risk of Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome (AWS) nor standardized treatment protocol for AWS. In the 6 months prior to our study, 30% of inpatients at UNC with AUD in their problem list experienced severe withdrawal. Early identification and management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome is necessary to reduce length of stay, morbidity and mortality. While Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) is a useful scoring tool for patients already experiencing withdrawal, the PAWSS (Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale) tool is the first validated tool to identify patients at risk for complicated AWS 1. Benzodiazepines have long been the mainstay of treatment for alcohol withdrawal but are not safe nor appropriate for all patients. Phenobarbital presents an alternative to conventional benzodiazepines and is also used in the management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome2,3. In our quality improvement study, we hoped to combine both a new screening method for AWS and standardized treatment protocol to reduce morbidity and mortality from AWS.

Methods: Our quality improvement project was jointly conducted with internal medicine hospitalists, nursing, pharmacy and addiction medicine. We implemented the PAWSS tool within EPIC for admitting physicians to use to identify patients at moderate/severe risk for AWS (PAWSS 4). A phenobarbital standardized protocol, created as an EPIC orderset, was initiated for patients at high risk for AWS. An EPIC dotphrase was created to autogenerate reminders to calculate the PAWSS score and treat with phenobarbital therapy when appropriate using the standardized protocol. Educational sessions were conducted to teach hospital medicine providers how to use the PAWSS tool an phenobarbital order set. To monitor the implementation of the interventions, using Business Objects (BO) we pulled all patients admitted to Hospital medicine with a diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal on their problem lists from July 2023 to September 2024. We gathered data around the usage of PAWSS tool and utilization of the Phenobarbital order set. We also looked at hospital length of stay as well as escalation to a higher level of care.

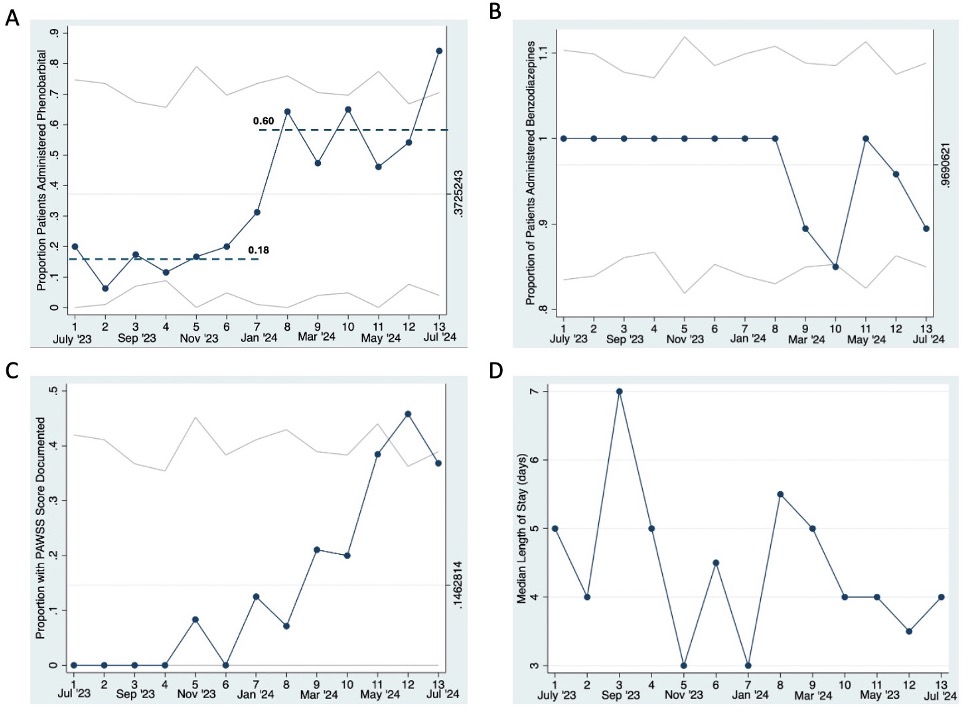

Results: The data shows post intervention phenobarbital administration increased three-fold (18% to 60% ) (1A). Data also revealed benzodiazepine use initially dropped but was not consistent over time (1B). There was also a positive uptake in providers using PAWSS (1C). Notably. there was reduction in the length of stay (1D). These metrics show that our intervention had significant impact on multiple metrics with strong clinical significance.

Conclusions: The introduction of the PAWSS tool calculator to identify patients at higher risk of withdrawal combined with a standardized phenobarbital protocol has the potential to reduce variability in care practices, leading to shorter length of stay and reduce escalation to higher level of care.The results of this study supported dissemination and implementation of standardized phenobarbital protocol and the PAWSS tool in the UNC ED as well as at UNC Chatham Hospital. Continual refinement of these protocols through iterative PDSA cycles will prove essential to gain further knowledge about best practices for management of alcohol withdrawal management.