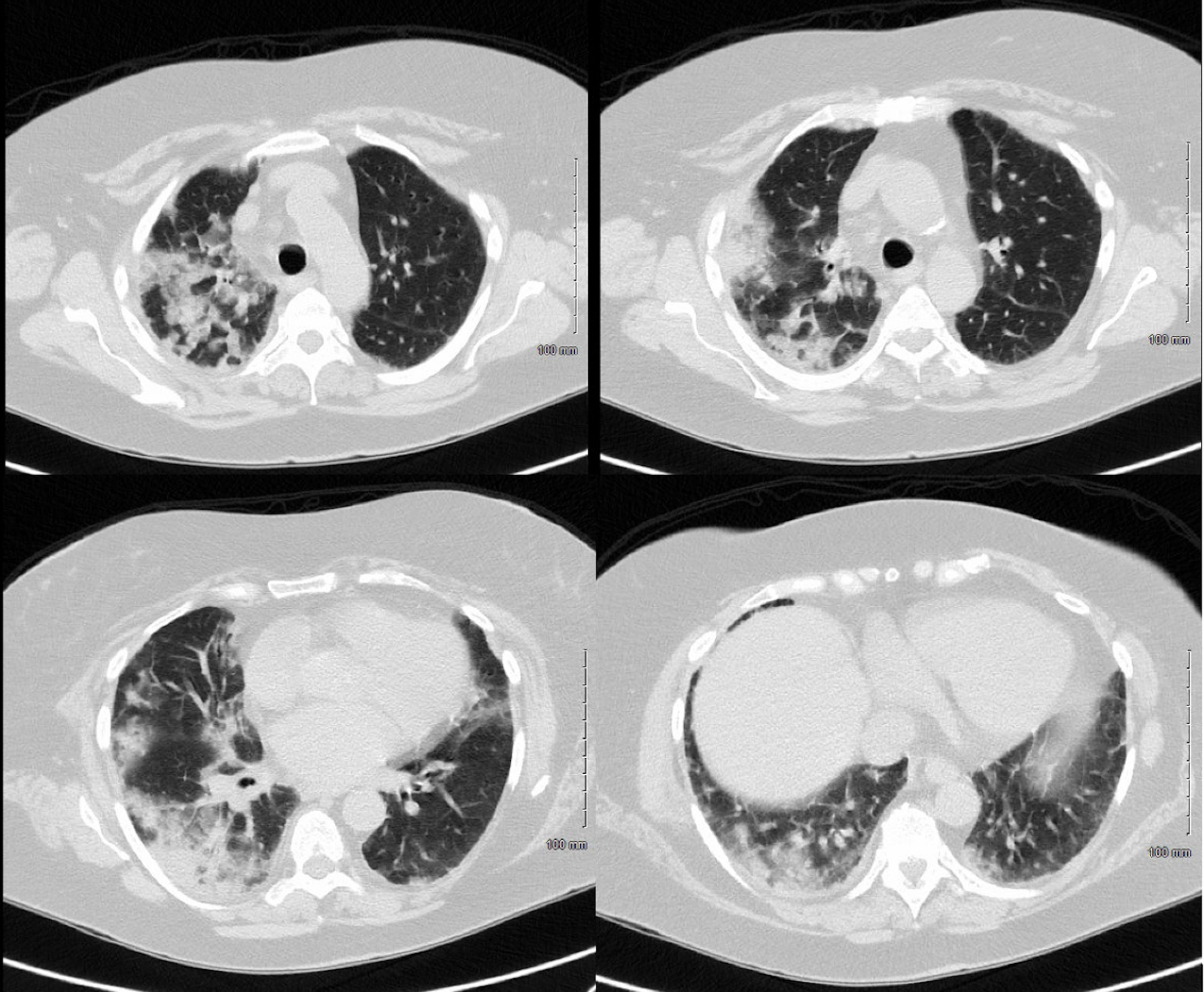

Case Presentation: Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP) is a rare condition and is often idiopathic, but among drug-induced causes, daptomycin-associated AEP is the most common.[1] The patient is a 75-year-old female with a past medical history of Sheehan syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism, and type two diabetes mellitus admitted to the hospital with a non-productive cough ongoing for one month, acutely worsening for three days, and a cutaneous abdominal ulceration. The ulceration began three weeks prior at an insulin injection site and was treated with six days of doxycycline, seven days of daptomycin, and then two days of ertapenem and daptomycin without improvement (Figure 1). On hospital admission, the patient was started on stress dose steroids with hydrocortisone 50 mg daily due to Sheehan syndrome. CT chest was interpreted as extensive ground glass opacities and consolidations, suspicious for multifocal pneumonia vs. an inflammatory process (Figure 2). Vancomycin and cefepime were initiated but discontinued two days later due to procalcitonin < 0.25 ng/mL for 48 hours and a positive parainfluenza virus 3 test on her respiratory panel. A biopsy of the abdominal ulcer was consistent with pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), and hydrocortisone was switched to prednisone 60 mg daily. The patient’s cough predated daptomycin use. Nonetheless, there was concern for eosinophilic pneumonia based on daptomycin exposure. Bronchoalveolar lavage showed fluid eosinophilia. Further infectious workup was negative for acid-fast bacilli, fungus, and bacteria. Following clinical improvement, she was discharged from the hospital with instructions for an oral steroid taper for AEP and PG.

Discussion: AEP is rare and remains uncommon following daptomycin use. We present this case to discuss the importance of ruling out eosinophilic pneumonia in hospitalized patients who have nonspecific respiratory symptoms and have received known inciting drugs, even in the presence of other possible causes for their symptoms, to prevent unnecessary morbidity from AEP. Our patient was unique in that her presentation was complicated by co-occurring PG. The pulmonary manifestations of pyoderma gangrenosum have been explored in the literature. In a recent review of 29 cases, these manifestations include neutrophil-predominant inflammation, cavitating and non-cavitating lesions, pleural effusions, fibrosis, granulomas, ulcerations, and necrotizing tracheitis, but not eosinophilic pneumonia.[2] We hypothesized that the patient presented in a pro-inflammatory state due to PG, making her pulmonary epithelium more vulnerable to daptomycin-induced injury and inflammation.[3] It is possible that our patient developed AEP in association with PG prior to the administration of daptomycin, as her cough predated daptomycin administration, which could represent a new syndrome.

Conclusions: This case of acute eosinophilic pneumonia presented in the setting of a cough that predated daptomycin use and an ongoing viral respiratory infection, which obfuscated the underlying diagnosis of AEP. We stress the importance of ruling out eosinophilic pneumonia at the earliest suspicion in hospital medicine, with a low threshold when known inciting medications have been used.