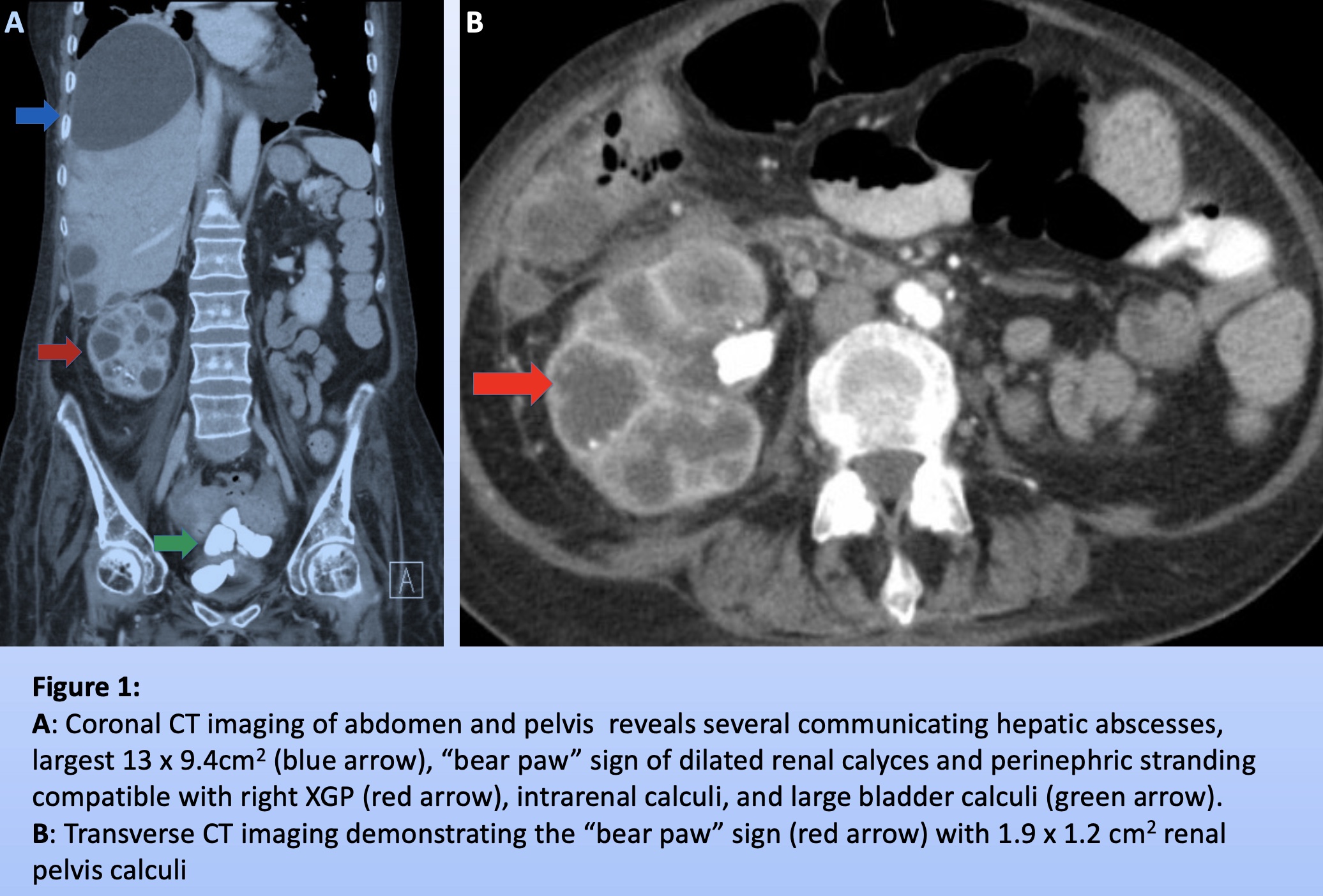

Case Presentation: A 58-year-old woman with multiple sclerosis, neurogenic bladder with indwelling catheter, and recurrent nephrolithiasis presented with worsening malaise and dizziness. Vitals signs were stable and physical exam was remarkable for baseline lower extremity weakness. Blood work identified leukocytosis (14.2 x 109/liter) and severe anemia (6.6 grams/deciliter). Urinalysis showed pyuria and calcium oxalate crystals.CT imaging (Fig. 1) revealed bladder calculi, largest 3x2cm2, and right renal calculi, largest 2x2cm2, with communicating hepatic abscesses, largest collection 13×9.4cm2. CT appearance of the right kidney showed the “bear paw” sign indicating fatty infiltration, consistent with xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis.Hepatic abscesses were drained, totaling 700cc. Post-drainage CT revealed near total resolution. Cultures grew S. anginous and B. fragilis. Following two-week treatment with levofloxacin and metronidazole, the patient was scheduled for nephrectomy and cystolithotomy with placement of suprapubic catheter.

Discussion: Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (XGP) is a rare complication of chronic obstructive nephrolithiasis. Granulomatous tissue with lipid-laden macrophages destroy the kidney, which can be mistaken for renal cancer. In one study, all XGP patients had renal calculi, 34% with staghorn calculi and 85% were female.Typical XGP symptoms include fever, malaise, anorexia, flank pain, and a renal mass. Workup reveals pyuria, anemia, elevated ESR, and liver function abnormalities, indicating biliary retention. XGP is usually unilateral and is associated with gram negative organisms, commonly E. coli; however, cultures may be sterile. Because this entity can be diffuse or focal, it is crucial to distinguish XGP from renal carcinoma, septic emboli, renal abscess, and malacoplakia.Recurrent nephrolithiasis induces a prolonged immune reaction. Three layers are observed: an inner layer of necrosis caused by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and lipid-laden macrophages, a middle layer of granulation tissue, and an outer layer of giant cells and cholesterol clefts. These inflammatory processes lead to fistula formation.Hepatic and intrathoracic extension have been rarely reported in the literature. In one case following total nephrectomy, a hepatic abscess was incidentally discovered. In cases with extrarenal extension, treatment consists of nephrectomy, fistula closure, and abscess drainage.

Conclusions: XGP is commonly caused by recurrent nephrolithiasis and indwelling urinary catheters. In patients presenting with hepatic abscesses and a history of chronic nephrolithiasis, it is critical to consider XGP with extrarenal abscess formation for appropriate treatment.