Background: Among all hospitalized patients with diabetes mellitus, about 40-50% require insulin at discharge. Insulin is a high-risk medication, associated with many errors including missed dosing, inaccurate dosing, or prescription of the wrong type of insulin. Many of these errors can occur during transitions of care including discharge and in patients with poor diabetes knowledge. Education, structured discharge planning and an interdisciplinary approach, including support during the hospital stay and post discharge may help to reduce medication errors and readmissions. Anecdotally, we found the discharge practices of providers at our hospital with regard to patients with diabetes mellitus is heterogenous and frequently lacking specific discharge instructions related to diabetes. We conducted a survey to understand discharge practices for diabetic patients who require insulin at the time of discharge with an eventual goal to improve care.

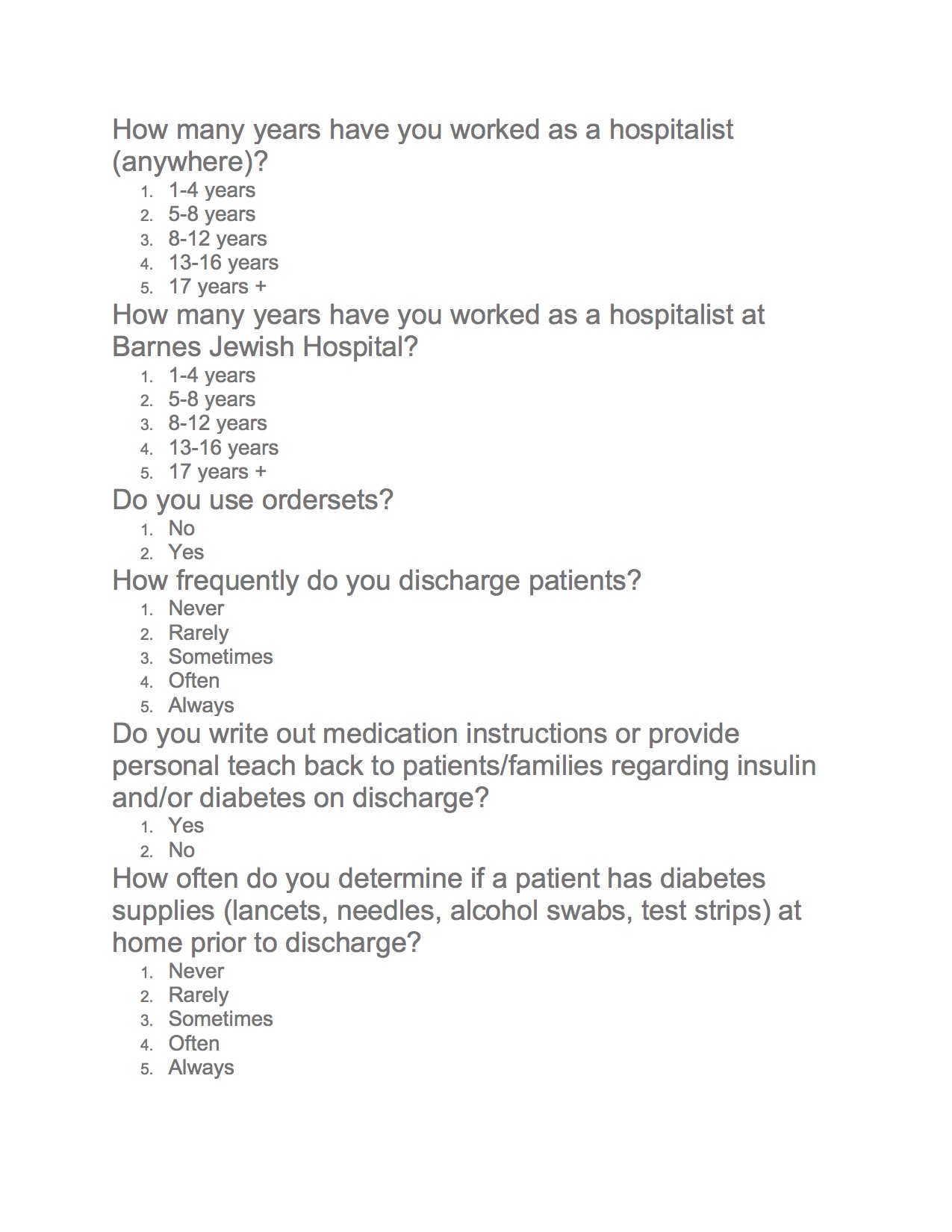

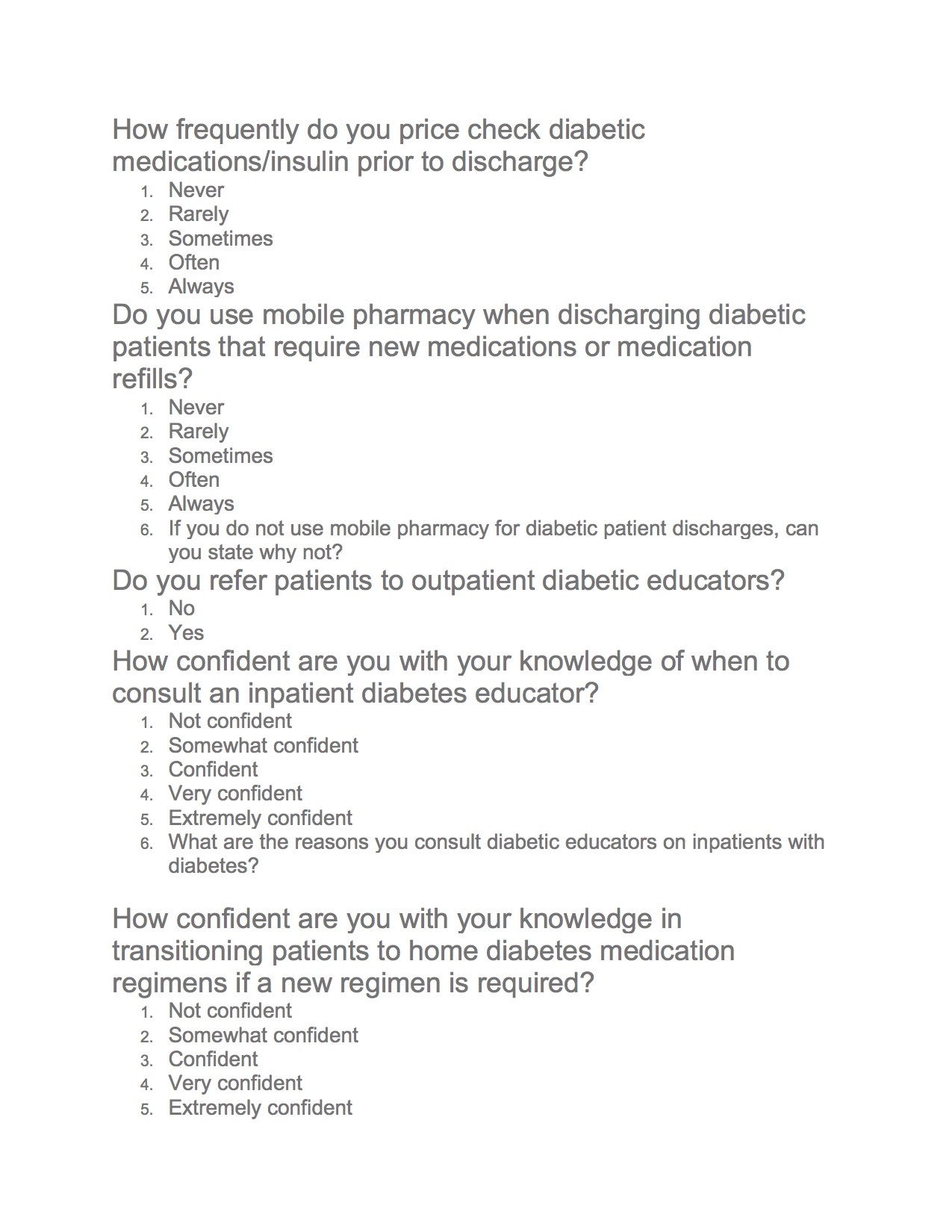

Methods: Internal data regarding patients discharged on insulin, length of stay and readmission rates in patients with diabetes was collected from our hospital patient safety and quality department. We devised a survey to assess discharge and inpatient diabetes-related practices among providers in the Division of Hospital Medicine. The survey was administered on Qualtrics via email and advertised during our division’s noon conference. The survey (attached) was designed to gauge participants’ use of diabetes-related order sets (and others), as well as assess our practices regarding diabetic educators, patient education, discharge instructions, and outpatient diabetes medication regimens.

Results: We had a 28% (43 of 156 faculty) survey response rate. 53% of respondents were in practice for 1-4 years in Hospital Medicine. Order set usage was rated on a Likert scale of “never” to “always”. 98% of responders used the adult inpatient insulin order set, 84% used the hyperglycemia urgency order set, and 77% used the diabetes discharge order set. 37% of responders noted that they did not provide teach back or give written instructions on discharge. 56% did not regularly check to make sure diabetic supplies were available at home prior to discharge. 72% did not refer to an outpatient diabetes educator. 21% were less than confident in transitioning patients to an outpatient medication regimen. The most common reasons to consult a diabetic educator were frequent admissions, poor understanding or new diagnosis of diabetes. Cost of insulin, lack of outpatient follow up and patient education were listed as some of the barriers faced while discharging diabetic patients.

Conclusions: Based on our data, promoting order set and “dot” phrase use, appropriate diabetes educator consults, and patient/provider education will help standardize our division’s diabetes care practices and are our initial targets for intervention. Subsequent steps will be to improve diabetic educator efficiency and examine the large-scale implications of our interventions on length-of-stay, readmission rates, and diabetes care metrics.