Background: Automated bidirectional text messaging has emerged as a compelling strategy to facilitate communication between patients and the health system after hospital discharge. Understanding the unique ways in which patients interact with these messaging programs can inform future efforts to tailor their design to individual patient styles and needs. The aim of this study was to characterize distinct patient interaction phenotypes with a post-discharge automated messaging program.

Methods: This was a secondary analysis of data from a trial which tested a 30-day automated text messaging intervention among primary care patients after hospital discharge. We analyzed text messages and patterns of engagement among patients who received the intervention and responded to messages. We first engineered features intended to describe patient interaction patterns along two axes: 1) Engagement style (rate of response to program check-in messages, frequency of inbound messages, average response time to program messages, request for help outside of a program check-in, frequency of specific categories of need) and 2) Program conformity (error rate among messages sent and average message character count). We then used an unsupervised machine learning approach (K-means clustering) to segment program participants into distinct interaction phenotypes. Finally, we looked at the association between these interaction phenotypes and 1) Patient demographic and clinical characteristics and 2) Hospital revisits. We used a chi-square test to test for differences in the rate of revisits across clusters.

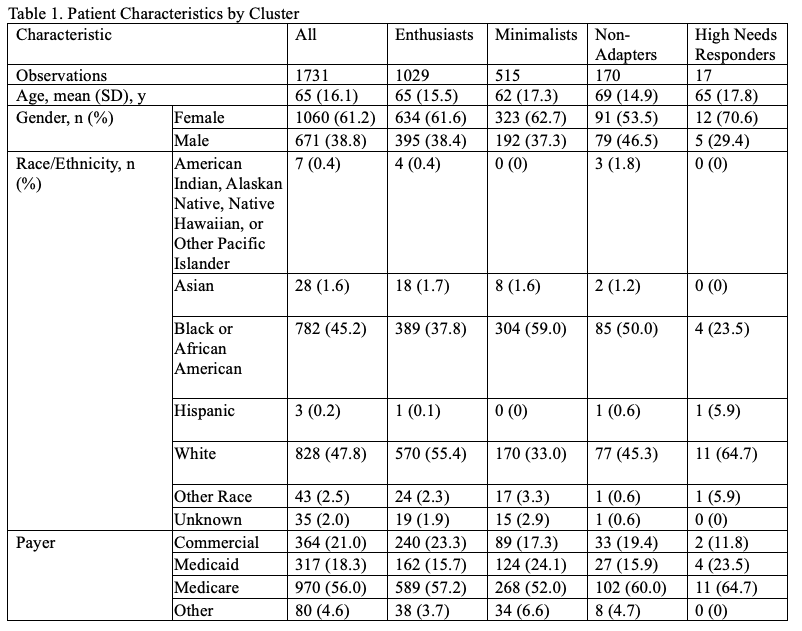

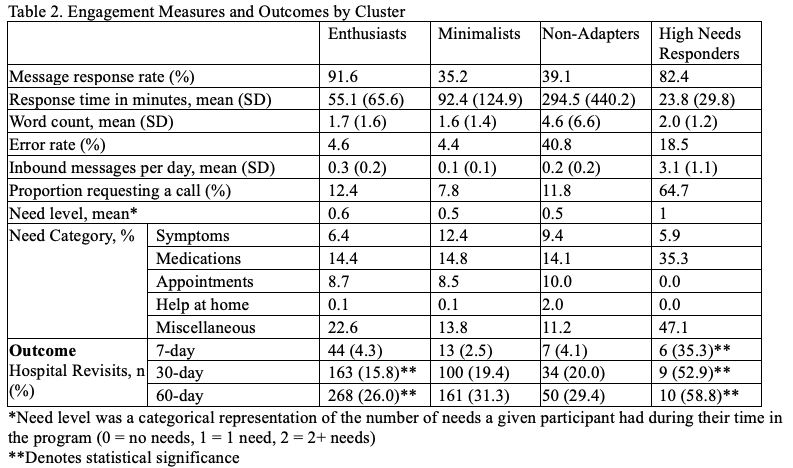

Results: A total of 1731 patients engaged with the messaging intervention and were included in the analysis, among which 1060 (61.2%) were female; the mean (SD) age was 65 (16.1); 782 (45.2%) and 828 (47.8) identified as Black and White, respectively; and 970 (56.0%) and 317 (18.3%) were insured by Medicare and Medicaid, respectively (Table 1). Using K-means clustering, we observed 4 distinct clusters representing patient interaction phenotypes: 1) A high engagement, high conformity group (n = 1029) (“Enthusiasts”); 2) A low engagement, high conformity group (n = 515) (“Minimalists”); 3) A low engagement, low conformity group (n = 170) (“Non-Adapters”); and 4) A high engagement with intense level of need group (n = 17) (“High Needs Responders”) (Table 2). Differences were observed in demographic characteristics – including gender, race, and insurance type – across groups (Table 1). The rate of 30-day hospital revisits was markedly higher for Cluster 4 (High Needs Responders) (52.9%), and was lowest overall for Cluster 1 (Enthusiasts) (15.8%) (Table 2).

Conclusions: We identified 4 distinct patient interaction phenotypes with a post-discharge text messaging program, and observed differences in both patient characteristics and outcomes across these groups. For hospitalist groups and health systems looking to leverage a text messaging approach to engage patients after discharge, this work offers two main takeaways: 1) Not all patients interact with text messaging equally, and some may require either additional guidance or a different medium altogether, and 2) The way in which patients interact with this type of program (in addition to the information they communicate through the program) may have added predictive signal toward adverse outcomes.