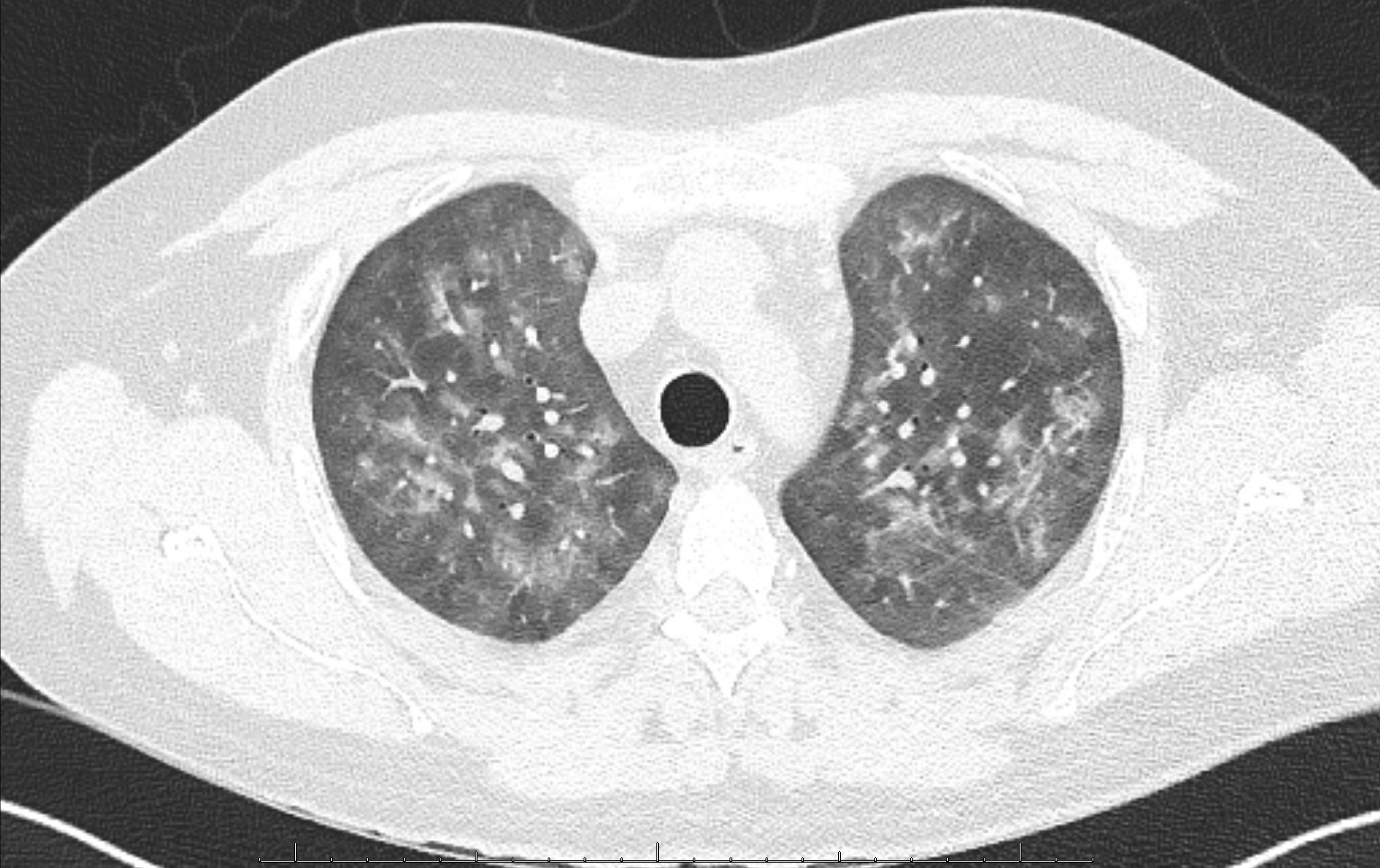

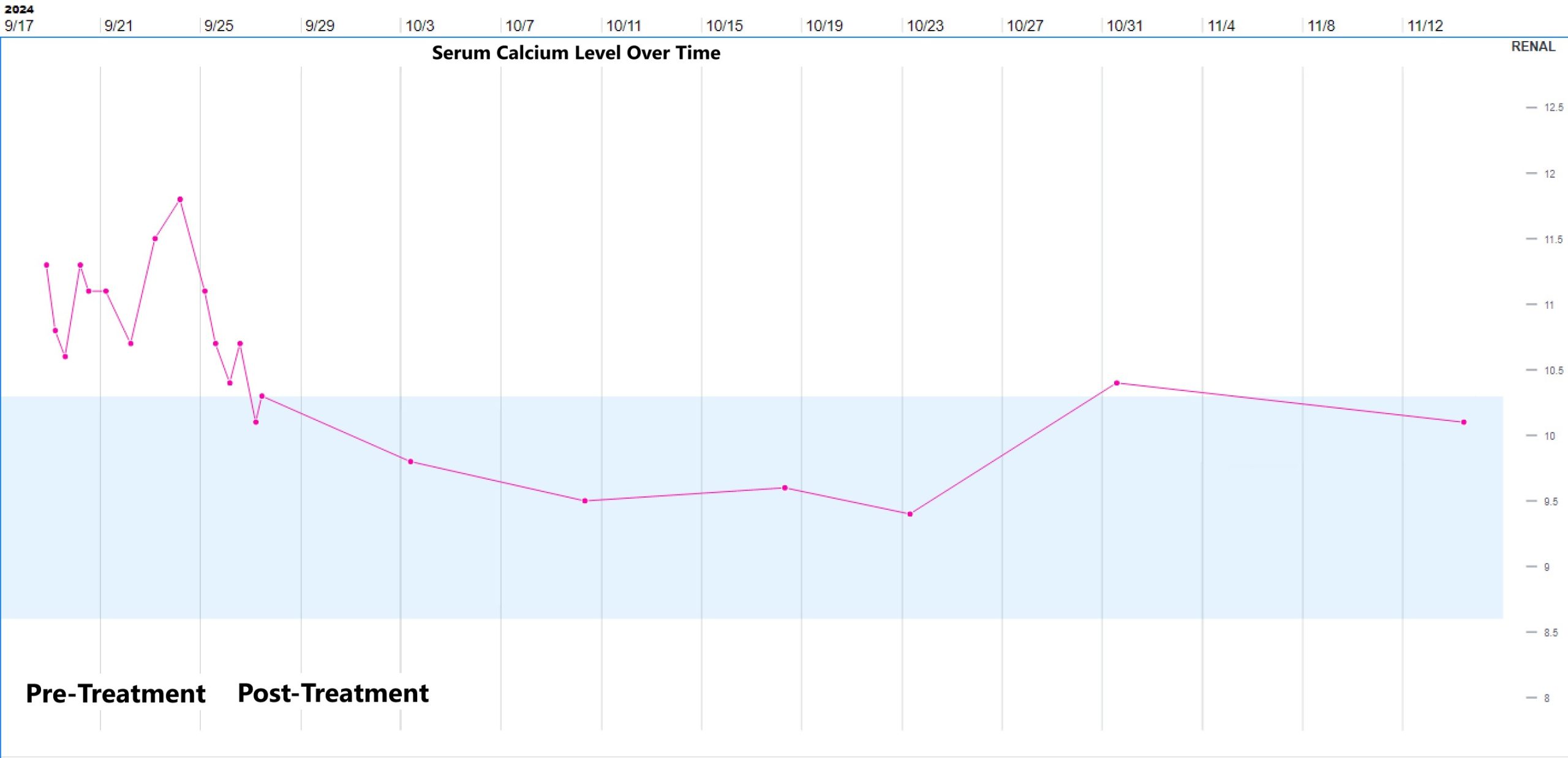

Case Presentation: A 33-year-old man with end-stage renal disease status post renal transplant was readmitted to the hospital with recurrent acute kidney injury (AKI).During his first admission, he reported a few weeks of nonproductive cough, dyspnea, congestion, chills, and recent nausea with vomiting. He was afebrile with normal vital signs and normal SpO2. Respiratory panel was positive for Rhinovirus. Labs showed serum creatinine of 2.6 mg/dL from a baseline of 1.6-1.9 mg/dL, as well as elevated serum calcium of 10.9 mg/dL with a normal serum albumin of 4.5 g/dL. He was treated with IV fluids, supportive measures for Rhinovirus, and his tacrolimus and prednisone were continued at usual doses while his mycophenolate dose was decreased by 50%. Over the two-day hospitalization, his symptoms improved, and his AKI resolved. His serum calcium also improved, to 10.4 mg/dL on the day of discharge. He was readmitted four days later with worsening symptoms, including nausea with vomiting, dyspnea, productive cough, and chills. He was noted to have intermittent temperatures to 99-100 degrees Fahrenheit associated with tachycardia, tachypnea, and an oxygen requirement of 2-3 liters. Chest radiograph showed bilateral interstitial opacities. Labs showed recurrent AKI, normal leukocyte count, and a mildly elevated procalcitonin level; the serum calcium was elevated at 11.3 mg/dL with a normal serum albumin of 4.2 g/dL. He was treated with IV fluids for AKI and hypercalcemia and antibiotics for possible pneumonia, but had persistent symptoms, AKI, and hypercalcemia. Serum PTH was low at 11 pg/mL (ref range 12-88), 25-hydroxyvitamin D (calcidiol) was normal at 35 ng/mL (ref range 13-62), and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol) was significantly elevated at 257 pg/mL (ref range 19-79). A Chest CT showed bilateral diffuse ground glass opacities with scattered peri-bronchial nodular consolidations (fig 1). Blood beta-D-glucan was positive, and PCR for pneumocystis jirovecii (PJP) was subsequently positive on induced sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples. Treatment dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was started, with resolution of fever, respiratory symptoms, hypoxemia, AKI, and hypercalcemia within 4 days (fig 2), at which point he was discharged. The calcitriol level checked 4 weeks after PJP treatment was normal.

Discussion: PJP associated hypercalcemia is uncommon and incompletely understood, but it has been described in multiple case reports (1,2) and may be related to granulomatous inflammation producing calcitriol. Granulomatous lesions, usually described as nodules on imaging, occur in about 5% of PJP cases (3). Hypercalcemia is associated with many granulomatous diseases and best described in sarcoidosis where 1-a-hydroxylase in macrophages converts calcidiol into calcitriol independent of PTH (4-6). A recent study in PJP found elevated calcitriol in serum and BAL samples prior to treatment with decreases post-treatment, supporting a link between PJP and calcitriol (7).

Conclusions: Immunocompromised patients present challenges with multiple diagnostic considerations. In our patient’s case, we suspect he had early PJP with superimposed Rhinovirus at initial presentation, which evolved to worsening PJP prompting his readmission. In light of the evidence for PJP mediated hypercalcemia and the significantly reduced mortality with early diagnosis and treatment (8), PJP should be considered in appropriate patients presenting with respiratory symptoms and non-PTH mediated hypercalcemia.