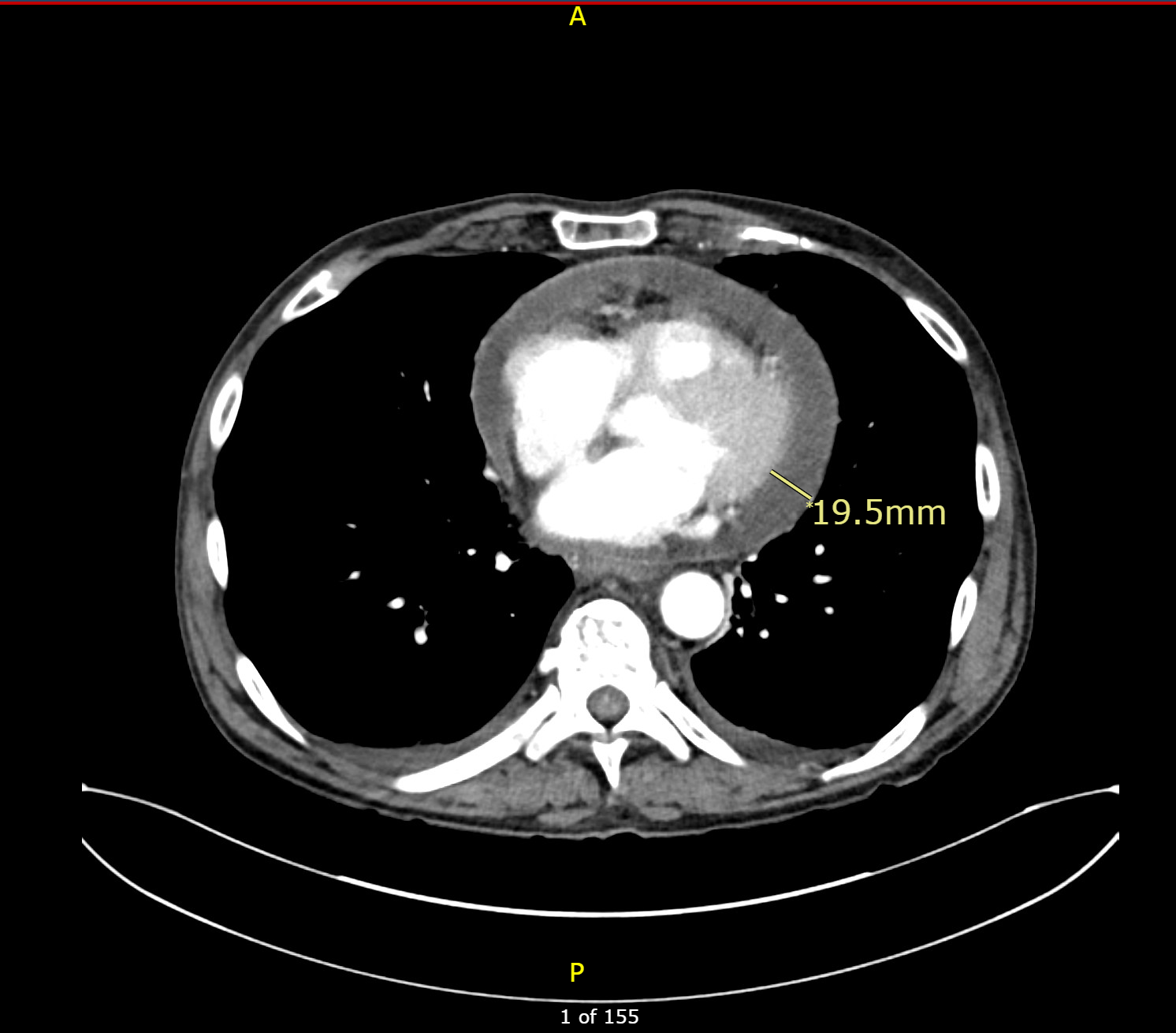

Case Presentation: A 66-year-old male with history of intravenous (IV) drug abuse presented with acute onset substernal chest pain and shortness of breath for one day. Initial EKG showed diffuse ST-elevations. Urine toxicology screen was positive for cocaine, cannabinoids, and fentanyl. CXR showed a hilar mass, which on CT showed a right upper lobe nodule presumptively representing a metastatic primary with bulky metastatic mediastinal and hilar adenopathy. A urine culture revealed Klebsiella pneumoniae and was started on trimethoprim-sulfomethoxazole. Bronchoscopic biopsy was done, and intraoperative cytology suggested small cell lung cancer which was later proven on tissue exam. A lung biopsy also revealed Actinomyces. However, repeat CT chest done for staging showed increasing pericardial effusion. Echocardiography showed increased pericardial effusion with impending cardiac tamponade but had no evidence of endocarditis. The patient had a pericardial window; 300 ml of pericardial fluid was removed. The pericardial fluid culture was positive for Serratia marcescens, which was subsequently managed with piperacillin-tazobactam. Pericardial biopsy did not reveal any malignancy. He underwent chemotherapy with etoposide and carboplatin first cycle for three days and was later discharged on ceftriaxone for six weeks and trimethoprim-sulfomethoxazole for 2 weeks.

Discussion: Serratia marcescens causes a wide range of infections, including urinary, respiratory, biliary tract as well as catheter-related infections. However, pericarditis is extremely rare. Bacterial infections are an infrequent cause of pericarditis, with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus being the most common pathogens. Our literature review revealed only one reported case of pericarditis caused by Serratia marcescens. Serratia bacteremia is most commonly observed in patients with a history of intravenous drug abuse. Pericarditis can lead to several complications such as tamponade, recurrences and constriction. In the developed world, acute pericarditis is most commonly idiopathic or viral in origin, and such cases are rarely associated with large effusions. The causes of such large pericardial effusions are commonly idiopathic, neoplastic, tubercular or related to myxedema but other infectious etiologies are less commonly considered in such cases. The rapid accumulation of pericardial effusion necessitates a thorough infectious workup, particularly when commonly observed causes such as blunt trauma, ascending aortic dissection, and cardiac rupture following procedures are absent. Blood and pericardial fluid bacterial and fungal cultures should always be performed to guide appropriate treatment. Malignant pericardial effusion always has a high risk of cardiac tamponade. However, infectious etiologies should also be considered, particularly in patients with relevant risk factors. These may lead to rapidly growing effusion and mortality in untreated patients goes up to 85%. Prompt treatment is critical to improving outcomes.

Conclusions: This case illustrates the possibility of Serratia pericarditis as a cause of rapidly growing pericardial effusion. Risk factors such as IV drug abuse, should raise suspicion towards the diagnosis of infectious etiology. Early diagnosis and treatment is crucial to prevent complications such as cardiac tamponade.