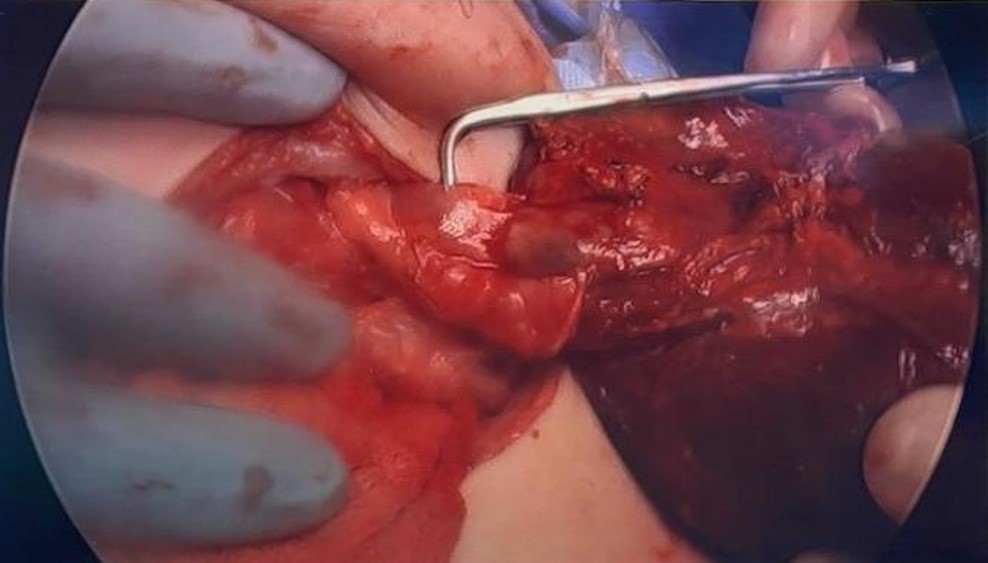

Case Presentation: A 3-year-old previously healthy female presented as a transfer from an outlying facility with a 1.5-week history of no stool output and progressively worsening abdominal pain. Trials of polyethylene glycol at home were unsuccessful. She subsequently developed a distended, firm, acute abdomen on the day of admission. There was no associated fever, vomiting, or preceding illness.CT imaging demonstrated uniform gaseous bowel distension concerning for an ileus and fecal impaction, as well as a non-visualized spleen suggestive of congenital asplenia (Figure 1). Labs revealed an extreme thrombocytosis of 1500 × 103/µL, leukocytosis of 24 × 103/µL, and anemia of Hgb 8.7 g/dL. The patient was initially placed on bowel rest with nasogastric (NG) decompression and empiric antibiotic coverage with piperacillin-tazobactam. Pediatric Surgery further reviewed the imaging and raised concern for a potential splenic infarct. While her spleen was not initially visualized on the CT scan, it was later found in an atypical location within the mid-abdomen with evidence of torsed vasculature. Follow-up doppler ultrasound demonstrated a lack of blood flow suggestive of splenic torsion and infarction.The patient was taken to the operating room for splenectomy. She was found to have a thickened, fibrotic pedicle with no ligamentous attachments to the spleen, indicating wandering spleen as the nidus of torsion (Figure 2). Following splenectomy, she showed clinical improvement and was discharged home a few days later on amoxicillin prophylaxis.

Discussion: Wandering spleen is a rare condition, uncommonly seen in toddlers between the ages of one and three [1]. The incidence rate is only 0.2% [2]. It is characterized by the congenital absence or underdevelopment of suspensory ligaments to the spleen [2]. This allows it to migrate to the lower abdomen or pelvis where it may be mistaken for an unidentified abdominal mass. Acute torsion around the vascular pedicle may also occur, with symptoms ranging from an asymptomatic or painful abdominal mass to an acute abdomen. If left untreated, acute torsion may lead to splenic infarction and gangrene. Detorsion and splenopexy are the mainstays of treatment, though splenectomy may be necessary if signs of hypersplenism, thrombosis, or infarction are present [3].

Conclusions: This case highlights the importance of considering wandering spleen in the differential diagnosis for pediatric patients presenting with acute abdomen and thrombocytosis. Early recognition and surgical intervention are crucial for optimizing patient outcomes and preventing severe complications. Further research and awareness efforts are therefore warranted to improve recognition and management of this condition in pediatric patients.