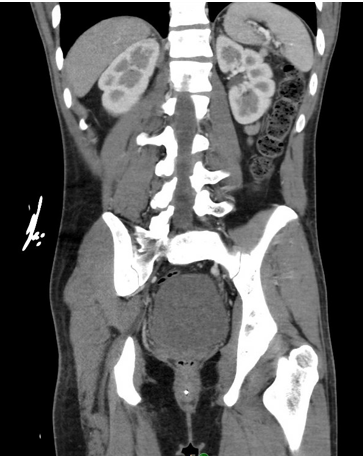

Case Presentation: A 23-year-old man without prior medical history was brought to the ED from his home for profound somnolence which had progressed over two days. EMTs at the scene noted that the patient was sluggishly responsive to painful stimuli. Initial vital signs were within normal limits, and a point-of-care glucose check was 28 mg/dL. He was given IV glucagon, and upon arrival to the ED, he had become slightly more interactive.Physical examination revealed a tired, but well-nourished young man with diffuse tan and hyperpigmentation of his buccal mucosa and palmar creases. Initial blood work showed microcytic anemia and thrombocytopenia (Hgb 7.5, platelets 126). A metabolic panel revealed normal hepatic enzymes, elevated creatinine, hyponatremia, and hyperkalemia (Cr 1.4, Na 121, K 5.7, CO₂ 18). A toxicology screen and respiratory pathogen panel were unremarkable. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed bilaterally atrophic adrenal glands, with no other intra-abdominal abnormalities. Based on these findings, the patient was suspected to have adrenal insufficiency and was treated with IV hydrocortisone and fluids.Overnight, the patient became suddenly bradycardic with a heart rate in the 20s and subsequent decline in responsiveness. He received inotropic support, which led to a quick improvement. Further serology indicated severe hypothyroidism, with a TSH level >50.00 and free T4 < 0.25. He was diagnosed with myxedema coma following adrenal crisis, with an underlying etiology of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2 (APS II). A thorough endocrinological evaluation revealed antibodies to 21-hydroxylase, thyroid peroxidase, and intrinsic factor.After several weeks of treatment with mineralocorticoids and thyroid hormone supplementation, the patient returned to normal life activities. Follow-up studies showed that his metabolic abnormalities and cytopenia had largely resolved.

Discussion: In this case, the patient’s presenting hypoglycemia was a critical clue that led to a timely diagnosis of endocrinopathy. The hypoglycemia was due to a combination of cortisol deficiency and delayed insulin clearance secondary to hypothyroidism. Hyponatremia and hyperkalemia were also key indications of adrenal insufficiency in this patient.Adrenal insufficiency is often the first endocrinopathy to manifest in APS II, with subsequent development of hypothyroidism, celiac disease, pernicious anemia, or autoimmune hypogonadism. APS II is a relatively rare condition, with an estimated prevalence of ~2 in 100,000 (1). Outside of a diagnosis of APS II, approximately 50% of patients with adrenal insufficiency will develop hypothyroidism (2), making this an important comorbidity to assess for in every patient with adrenal insufficiency. Treatment for polyglandular syndromes is largely identical to hormone therapy for each condition in isolation. In cases of concomitant adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism, it is crucial to administer steroids first to prevent adrenal crisis (3).

Conclusions: APS II is a rare syndrome that can mimic more common conditions such as sepsis or substance use, particularly in young patients. Early symptoms, such as skin tanning, fatigue, headaches, and reduced appetite, may be subtle and easy to overlook. However, failure to promptly identify and treat this condition can result in life-threatening consequences.