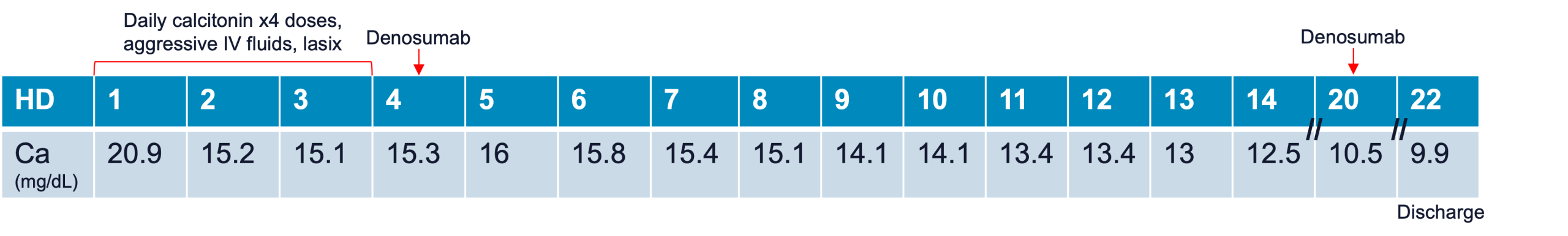

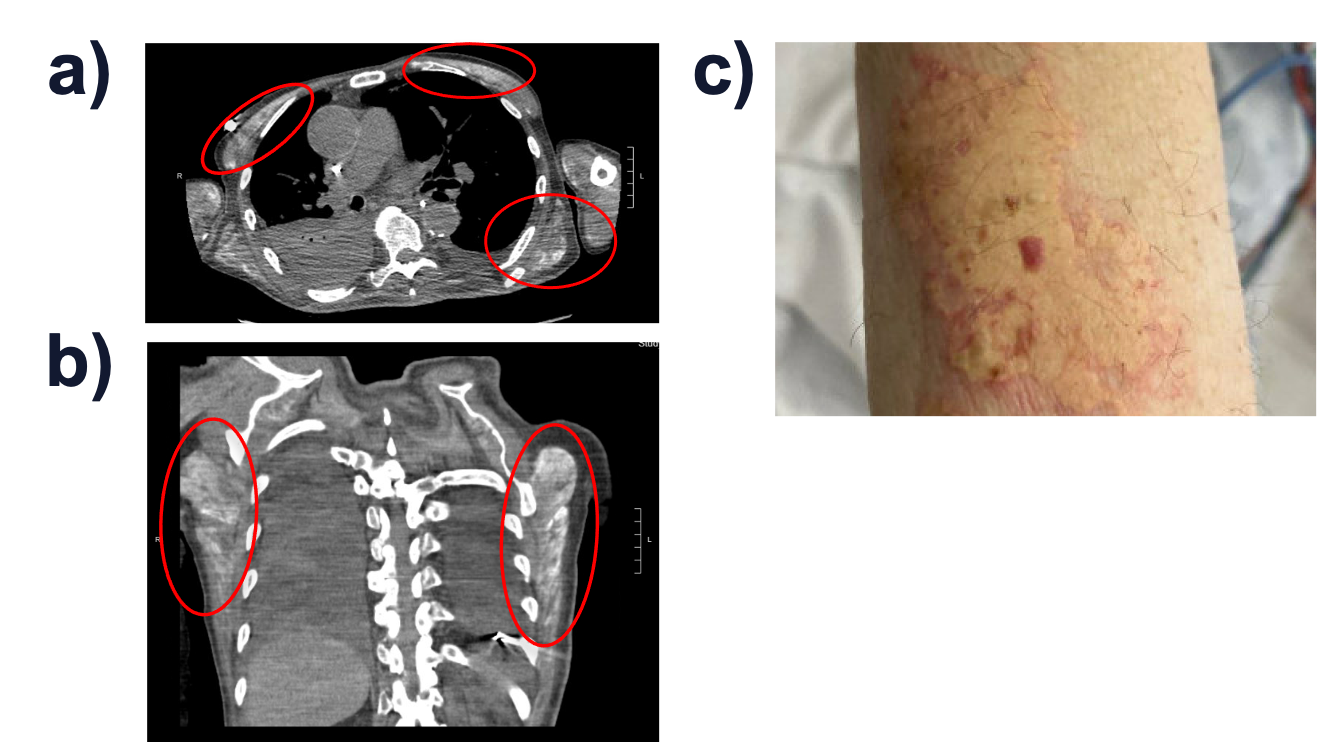

Case Presentation: A 76-year-old man with a history of epilepsy and prior stroke was admitted to the hospital medicine service for rhabdomyolysis complicated by renal failure requiring hemodialysis. His hospitalization was notable for persistent hypocalcemia requiring aggressive repletion despite hemodialysis, and he was discharged on calcium and vitamin D supplementation with normalization of renal function and calcium levels in the outpatient setting. Eight weeks after discharge, he was readmitted with altered mental status, weakness, and acute kidney injury (AKI). He was found to have a calcium of 19.4 mg/dL (corrected: 20.9 mg/dL) and an ionized calcium level above the detection threshold (> 1.8 mmol/L). A parathyroid hormone (PTH) level was suppressed; vitamin D, angiotensin converting enzyme, and PTH-related protein levels were normal. Calcium levels initially improved with fluids, furosemide, and calcitonin but plateaued at 14-15 mg/dL, after which denosumab was administered. The hypercalcemia was initially attributed to milk-alkali syndrome and deconditioning-associated immobility; however, markers of bone turnover (C-telopeptide, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, pro-collagen I peptide) were normal. A CT chest obtained to evaluate for subsequent hypoxia incidentally noted diffuse enhancement throughout the patient’s chest wall musculature, suggestive of calcium deposition or prior myositis. Review of his prior hospitalization was notable for development of calcinosis cutis of the right forearm two weeks into that admission. This raised suspicion that the current hypercalcemia was a consequence of delayed release from soft tissue calcium deposits formed during his prior rhabdomyolysis, further exacerbated by exogenous supplementation and deconditioning. After a second dose of denosumab, the patient’s calcium normalized. The patient’s renal function and mental status returned to baseline, and he was discharged on hospital day 22.

Discussion: Hospitalists commonly care for patients admitted for rhabdomyolysis and for hypercalcemia. Although rhabdomyolysis is often associated with hypocalcemia in the acute setting, there are rare reports of hypocalcemia followed by delayed hypercalcemia in patients with concomitant AKI [1-3]. While the exact mechanism remains unknown, hypocalcemia may develop during the oliguric phase due to the formation of soft tissue calcium deposits, as seen in our patient with calcinosis cutis and the incidental CT findings. This is then followed by hypercalcemia during the diuretic phase due to calcium release from these deposits. This explains the patient’s relative resistance to calcitonin and initial denosumab, since these agents primarily act to decrease calcium resorption from the kidney and bone. A pyrophosphate technetium scan can be used to identify soft tissue calcium deposits, if not already radiographically visualized.

Conclusions: Hospitalists frequently care for patients with rhabdomyolysis, which can result in AKI and metabolic abnormalities. Our case highlights the longitudinal manifestations of electrolyte derangements associated with rhabdomyolysis, which can arise weeks after resolution of acute insults. Hospitalists should be aware that hypercalcemia can rarely be the result of prior rhabdomyolysis with AKI; this may reduce unnecessary searching for other causes of hypercalcemia, such as extensive evaluations for malignancy.