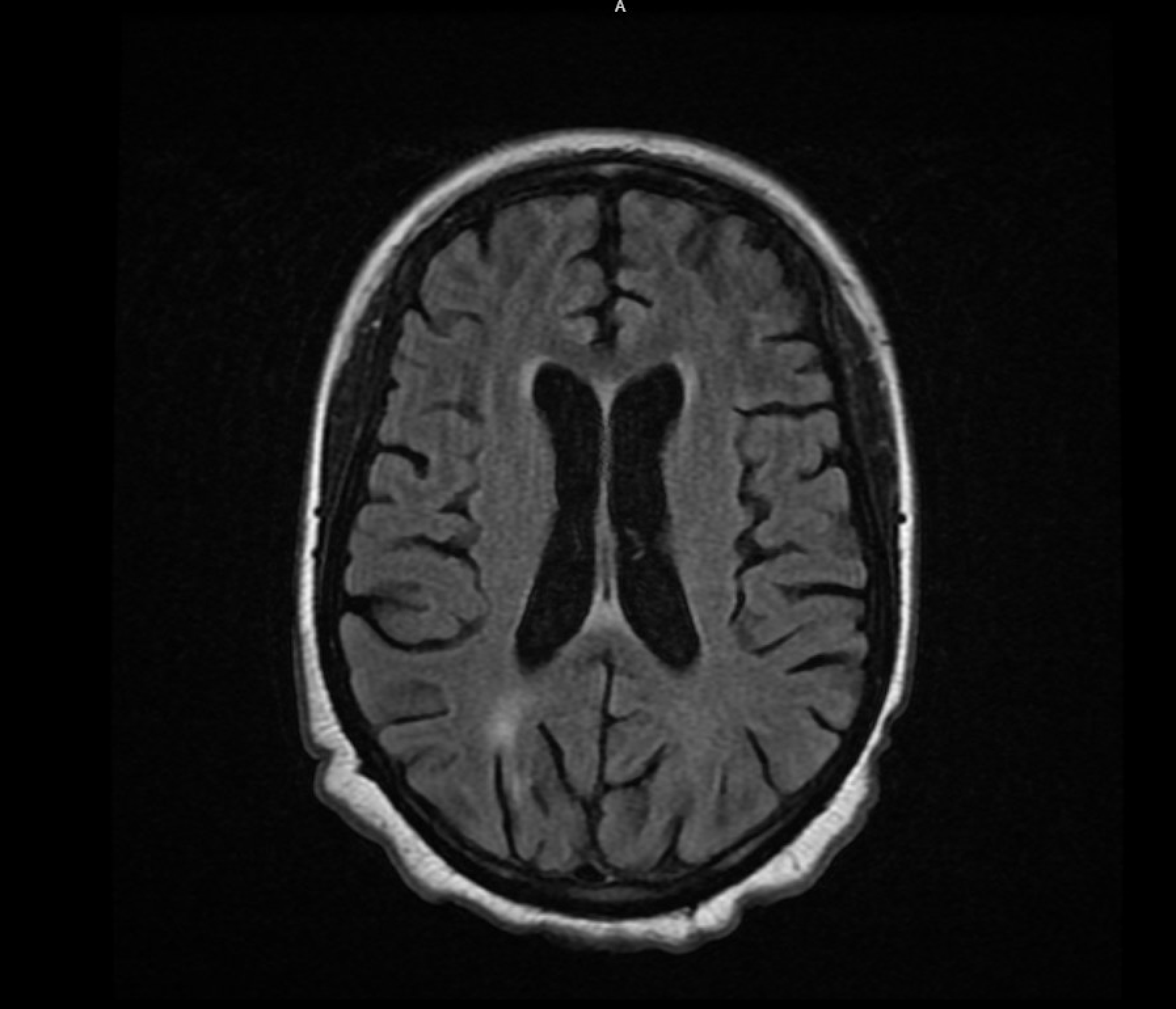

Case Presentation: A 27 year old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and history of a single seizure episode presented with acute altered mental status. The patient was initially disoriented and nonverbal, able to open eyes but unable to track, intermittently responding to commands, and later deteriorating, becoming obtunded and eventually comatose. Her NIH Stroke scale was 2 and no focal deficits were noted during the hospitalization. MRI findings revealed mild-to-moderate brain atrophy with patchy periventricular and subcortical hyperintensities, suggesting an inflammatory process. After ruling out meningoencephalitis with a lumbar puncture, she was diagnosed with Neuropsychiatric SLE (NPSLE), later complicated by multiple unprovoked seizure-like episodes. Three 24-hour video electroencephalograms (vEEGs) were negative for epileptic activity despite the presence of postictal states and tongue lacerations. Her treatment for lupus cerebritis led to improvements in mental status and neurological symptoms, although seizure-like activities persisted. Despite repeated negative EEGs, the patient was started on Levetiracetam 500 mg alongside 1mg Lorazepam as needed. Notably, the patient retained memory of one episode, and experienced two panic attacks suggesting concomitant psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) and anxiety. These PNES events occurred after administration of Levetiracetam, supporting the possibility of a dual diagnosis.

Discussion: Our patient experienced both PNES events with negative EEG and clinically apparent seizures. Her events continued even after her NPSLE responded to treatment. This prompted a multidisciplinary evaluation for her seizure-like episodes. Ultimately, the Neurology team decided her clinical symptoms of epileptogenic seizures that continued despite NPSLE treatment warranted AED therapy. Administration of levetiracetam stopped the patient’s clinical features of true seizures including tongue biting and postictal states, but PNES-suggesting events continued. We also acknowledged that the trauma and anxiety of her acute illness likely played a role in PNES events, and therefore was started on escitalopram.

Conclusions: 1.The dual diagnosis of PNES and epilepsy is a rare but crucial differential, especially in patients with altered mental status and unreliable or unattainable histories. 2. While EEGs play an important role in diagnosing and differentiating between PNES and epilepsy it is essential to acknowledge their limitations as a temporal snapshot.3. Initiating antiepileptic drugs in patients with PNES based on high clinical suspicion of a dual diagnosis can be rationalized, even without EEG-confirmed seizures.In addition to the conclusions above, hospitalists should recognize the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in managing complex conditions like NPSLE by coordinating care among neurology, psychiatry, and rheumatology. Initiating anti-epileptic drugs can be considered if a dual diagnosis of PNES and epilepsy is established with the support of consult teams. Also, prioritizing the psychological aspects of the illness is necessary, and strategies to reduce trauma and/or anxiety in the acute setting can be implemented. This case highlights the complexities of diagnosing and treating overlapping neurological and psychiatric conditions, emphasizing the need for hospitalists to integrate multidisciplinary collaboration, holistic care, and personalized strategies to enhance patient outcomes.