Case Presentation: A 49-year-old male with a history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy(HOCM), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, peripheral vascular disease, deep vein thrombosis, type II diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease stage 3b, and early-onset cataracts presented with chest tightness and shortness of breath of one-day duration. Vitals included blood pressure 222/72mmhg and tachycardia (110/min). Physical exam notable for short stature, BMI 11.5, prominent facial wrinkles, thin white hair, bilateral cataracts, and hoarse voice. Labs showed troponin 263 ng/L, proBNP 3817 pg/mL, creatinine 2.3 mg/dL (baseline 1.2 mg/dL). EKG showed sinus tachycardia with left ventricular hypertrophy, ST segment depressions in inferolateral leads with 1mm ST elevation in aVR. Suspecting Non ST elevation myocardial infarction, he received aspirin loading dose and heparin infusion. Echocardiogram showed ejection fraction of 45%, no clear regional wall motion abnormality. Coronary angiography showed 70% and 80-90% occlusions in the right coronary and left circumflex arteries, respectively. A total of three drug-eluting stents were placed, and aspirin and ticagrelor were started before discharge. Subsequent outpatient cardiac MRI was negative for infiltrative cardiomyopathy. This patient’s history of HOCM and myocardial infarction at a relatively young age was concerning for underlying genetic predisposition to early-onset severe cardiovascular disease. Patient s family history revealed siblings with similar physical features, developmental and cognitive delay, and his daughter suffered a coronary event at 14 years old. A referral to a genetic workup was made that revealed Werner syndrome as a diagnosis. Records from the distant past showed a genetic workup negative for muscular dystrophy.

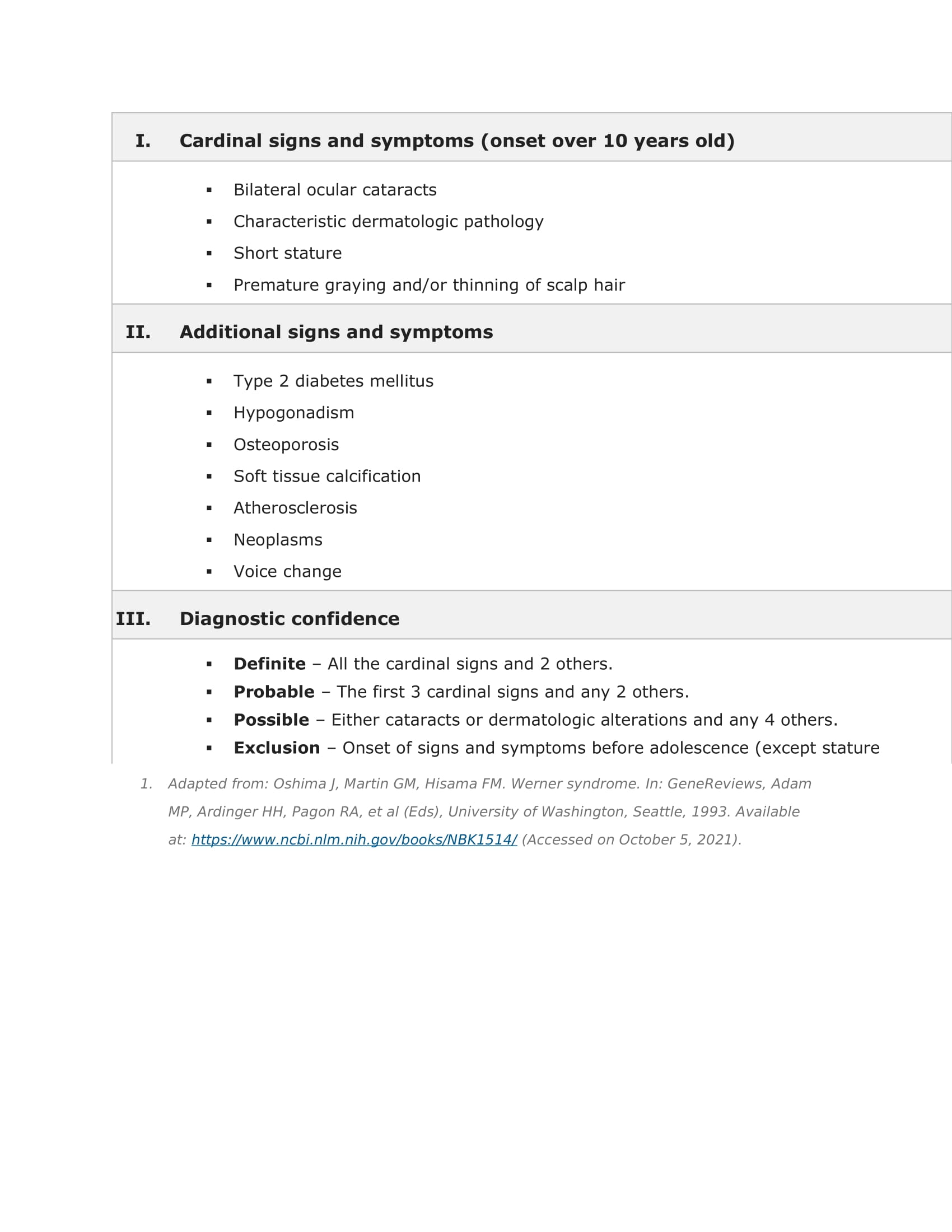

Discussion: Werner syndrome (WS) is an autosomal recessive progeroid disease characterized by premature or accelerated aging. While some features are present during childhood, WS often may not be recognized until the third or fourth decades of life. Premature graying and hair loss, vocal hoarseness, loss of subcutaneous tissue, muscular atrophy, skin changes, bilateral cataracts) are some of the significant findings(1,2). Later onset and longer lifespan distinguishes WS from Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), which presents in adolescence and often results in death during early teen years(3). The most common cause of death in both WS and HGPS is myocardial infarction, though death from malignancy is also more common in WS(2).Diagnosis of WS or HGPS is clinical but can be confirmed with genetic testing to identify WRN or LMNA mutations, respectively. These genes are suspected to participate in DNA damage responses and telomere metabolism, and mutations leading to vascular smooth muscle cell loss, and early cardiac tissue oxidative damage and fibrosis(4-7). These mutations may lead to fatty liver disease and renal dysfunction(8).

Conclusions: The combination of early-onset cardiovascular disease and prominent progeroid physical exam findings should raise clinical suspicion for genetic progeroid syndrome. Patients with suspected WS should undergo annual surveillance with ten-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk estimation, diabetes screening, osteoporosis monitoring, eye exams, and dermatologic exams(3). Patients and their families are also encouraged to complete comprehensive genetic counseling to discuss carrier testing and prenatal testing for at-risk relatives.