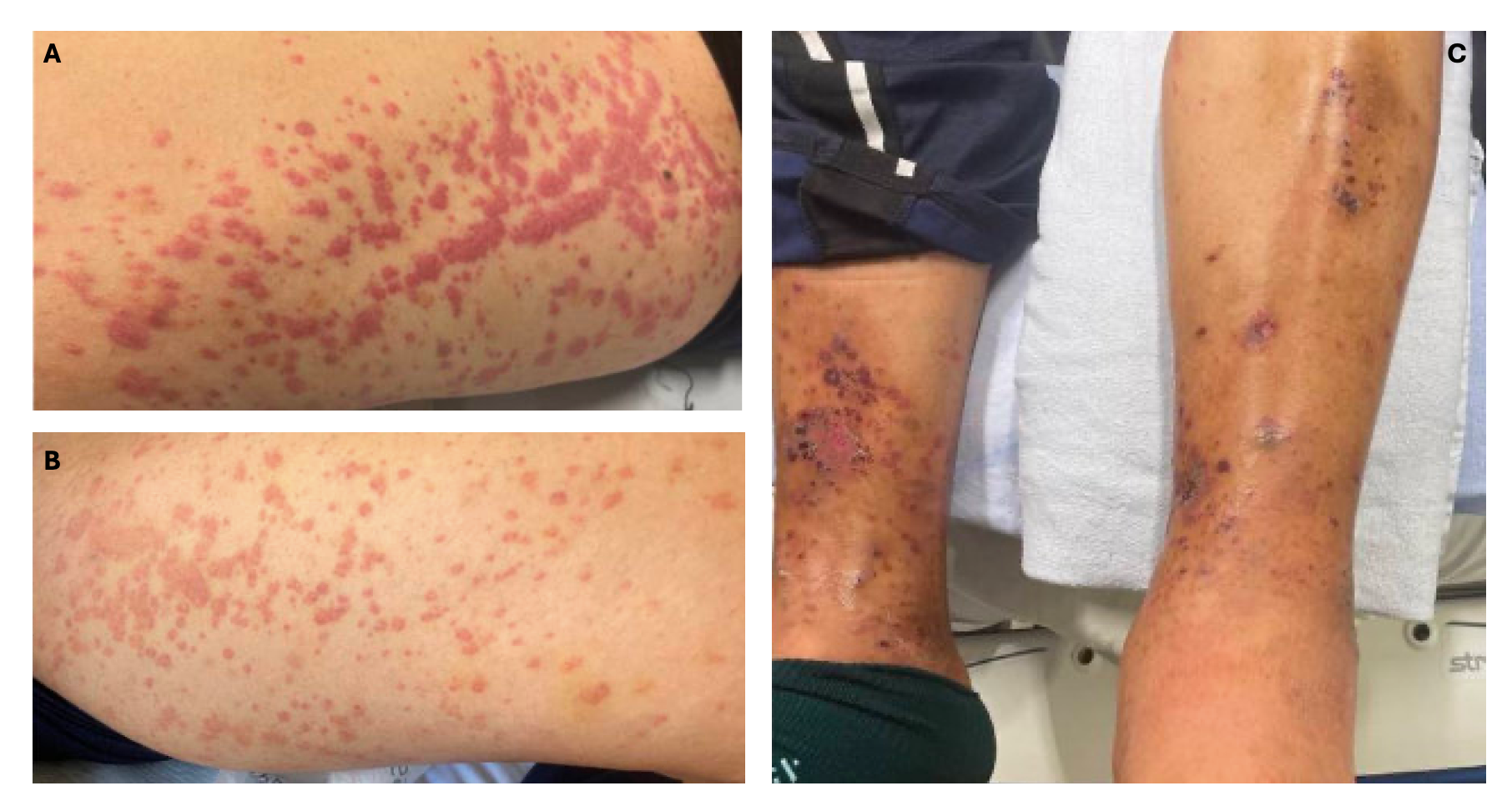

Case Presentation: Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) is a rare immune complex-mediated vasculitis of the dermal capillaries and venules, classically presenting with palpable purpura. Here, we report a case of LCV presenting with lower extremity rash and proteinuria.A 54-year-old man with a history of gout, eczema, and hyperlipidemia presented with two weeks of swelling and burning rash of the bilateral lower extremities (BLE). Associated symptoms included sore throat, nasal congestion, and epistaxis. He denied fevers, joint pain, or new medications, but did report “bubbly” urine.Vital signs were unremarkable. Physical exam was notable for BLE pitting edema, scattered purpuric papules, and coalescing bullae over the legs, buttocks, and forearms (Figure 1). Laboratory tests revealed a creatinine of 1.57 mg/dL from a normal baseline, urine protein to creatinine ratio of 0.73, and roughly 4g of proteinuria over 24 hours. C-reactive protein was elevated to 19 mg/L. Complete blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were within normal limits and an infectious workup was negative. A renal ultrasound was suggestive of medical renal disease.Although rheumatologic workup was negative for vasculitides, skin biopsy revealed small blood vessel injury with perivascular neutrophilic infiltration, suggestive of LCV (Figure 2). He was started on 60mg prednisone daily for 5 weeks with resolution of skin lesions. His proteinuria was deemed related to LCV and he was started on dapagliflozin and valsartan with outpatient plans for renal biopsy.

Discussion: Small vessel vasculitides, like LCV, are caused by neutrophilic infiltration of small vessels causing fibrinoid necrosis.1 LCV is rare and generally idiopathic but can be triggered by infections, medications, connective tissue disorders, and systemic vasculitides. An upper respiratory infection likely triggered this patient’s LCV. Streptococcal infections have frequently been linked with LCV.2 This patient had a classic presentation of LCV with pruritic purpura of the BLE; however, he had unique manifestations of AKI and proteinuria, which have been reported in 14% and 38% of cases, respectively.3 A thorough clinical exam is necessary as skin lesions above the waist are associated with renal involvement, as seen in this case.4 The gold standard for diagnosis of LCV is biopsy with direct immunofluorescence. Systemic symptoms prompt evaluation of secondary causes such as IgA nephropathy, ANCA-associated vasculitis or cryoglobulinemia.5 LCV can self-resolve in weeks to months in about 90% of cases, but high dose steroids are indicated if systemic involvement is present.3

Conclusions: This case underscores the diagnostic challenge of LCV presenting with systemic involvement, which can mimic more severe vasculitides such as ANCA-associated vasculitis. A methodical approach to the differential diagnosis of rash with systemic symptoms, guided by clinical and histopathologic findings, is essential. Assessment for systemic involvement should be pursued to assess need for more aggressive treatment.