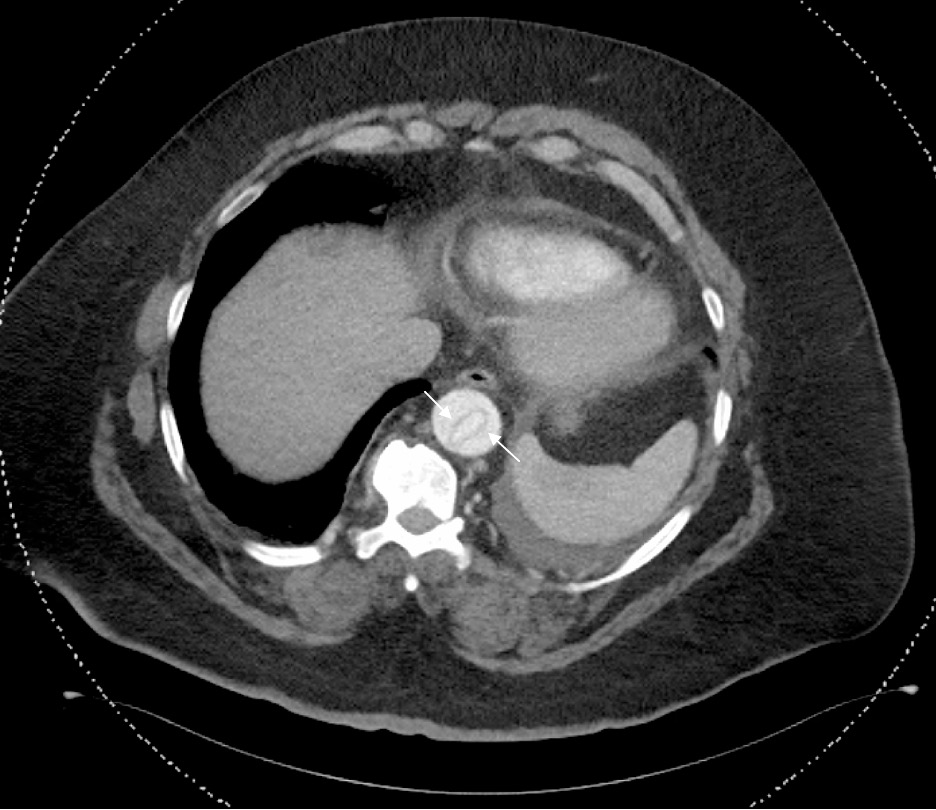

Case Presentation: A 61-year-old male with history of hypertension, asthma, and morbid obesity presented with left arm, chest, and face numbness, back pain, and shortness of breath at rest. He denied weakness with the numbness. His symptoms were akin to “being kicked by an elephant.” These symptoms had been worsening for one week prior to presentation. He visited an outside hospital one week prior and was diagnosed with pulmonary edema and discharged with furosemide. He denied trauma, injury, or surgery. He quit smoking and drinking alcohol three weeks prior.In the ER, the patient had sinus tachycardia to 110 bpm. His blood pressure was 160/100, and he was saturating 98% on room air. No differential extremity blood pressures were recorded. Neurological exam demonstrated 5/5 strength of the extremities. However, he had decreased sensation to light touch of the left upper extremity, chest, and face. Lungs were clear, although he was dyspneic. Stroke alert and MI workup were negative.CT head showed no hemorrhage or mass. Chest x-ray showed a tortuous aorta. Abdominal ultrasound ordered due to mildly elevated LFTs showed an incidental free intimal flap in the mid abdominal aorta. CT angiography showed a Stanford Type A aortic dissection from the aortic root to the left external iliac artery.Cardiothoracic surgery was urgently consulted following the ultrasound, and they recommended emergent transfer to an appropriately equipped hospital. CCU was also consulted but did not move the patient from the ER due to his tenuous status pending transfer. An esmolol drip was titrated to maximum dosage and was then switched to a nicardipine drip.Following transfer, aortic repair was performed that evening. The next morning, the patient was in severe shock resistant to multiple pressors and developed multi-organ failure requiring CRRT. ECMO was started, but shortly after initiation, the patient went into asystole. Resuscitation was unsuccessful.

Discussion: Aortic dissection is uncommon, with less than 10,000 cases annually in the US. The diagnosis can be overlooked when an atypical presentation raises clinical suspicion for other more likely diagnoses. Our finding of aortic dissection was incidental. Lumbar back pain is common and is often musculoskeletal rather than a dissection. Documentation at the outside hospital did not describe back pain as the overarching symptom.Neurological symptoms accompanying aortic dissection make diagnosing a dissection challenging. However, neurologic symptoms including weakness, tingling, and numbness may result from the dissection reducing blood flow to spinal and extremity arteries. Some studies describe neurologic symptoms in up to 40% of dissection patients.Once the diagnosis is suspected, CT angiography, MR angiography, or TEE establishes the diagnosis. Early surgical consultation is critical for an ascending aortic dissection, as surgical delays are associated with increased mortality. Prior to surgery, heart rate and blood pressure regulation reduce the risk of rupture. Esmolol or labetalol drips are preferred to maintain heart rate less than 60 bpm. In addition, a nitroprusside drip should be used to maintain systolic blood pressure between 100-120 mm Hg. Nitroprusside should only be used with a beta blocker to avoid reflex tachycardia.

Conclusions: Despite technological advances, an aortic dissection diagnosis can be challenging with an atypical presentation and neurological manifestations. It continues to be a humble reminder of the adage, “what one knows, one sees.”