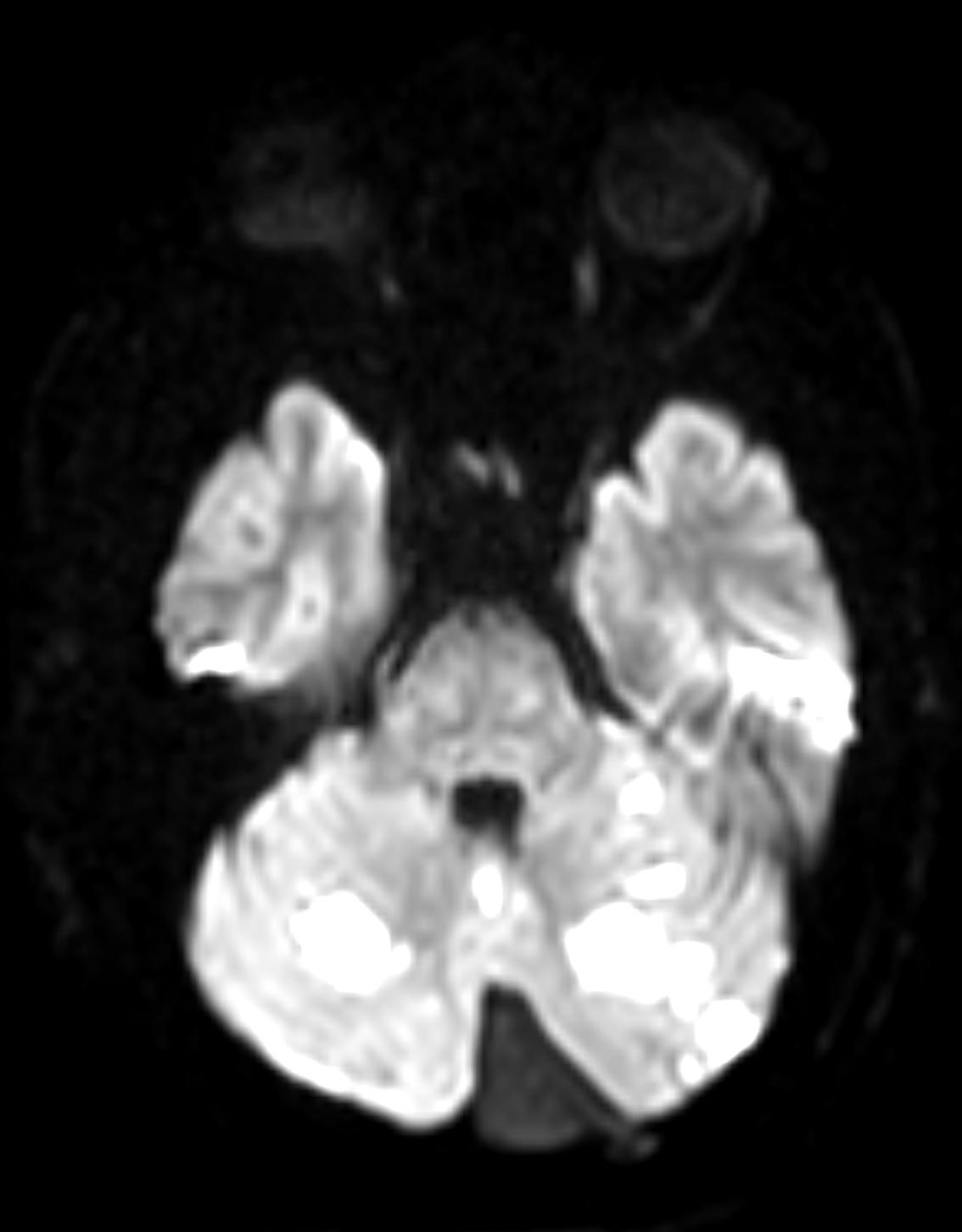

Case Presentation: Vertebral arterial dissections (VAD) while commonly associated with strokes in younger patients (below age of 45) can occur at any age. They are typically seen in patients with head or neck trauma having underlying vascular risk factors including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, tobacco use, and connective tissue disorders. Growing interest in physical fitness has resulted in rigorous workout routines which may pose a risk for strokes and awareness is necessary as signs and symptoms are often vague, leading to delay in diagnosis. We report a rare case of a healthy, 50-year-old male who presented with acute onset imbalance, vertigo, nausea, and non-bloody and non-biliary emesis while working out in the gym. He reported daily weightlifting as a part of his work out but started having nagging left neck pain for the past two days. The patient was given Aspirin prior to arrival to the ED. His NIH stroke scale during ED evaluation was 0, with no disabling deficits. As a result, he was not treated with intravenous thrombolysis. Initial computed tomography (CT) head and CT angiogram (CTA) head and neck were negative for acute intracranial abnormalities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain demonstrated acute to subacute posterior circulation infarctions of the cerebellum bilaterally, left thalamus, and medial left occipital lobe. Further review of the CTA with three-dimensional post processing confirmed mild irregularity of the left distal extracranial vertebral artery at the level of C1-C2 consistent with symptomatic vertebral artery dissection. Transthoracic echocardiogram did not reveal a patent foramen ovale, valvular pathology, or clots. Neurology evaluated the patient and recommended risk factor modification. The patient was started on aspirin for the dissection. Lipid panel showed LDL cholesterol of 75 md/dL, so he was started on Lipitor 40 mg daily. He remained normotensive prior to and throughout the hospitalization and was discharged home with outpatient follow-up.

Discussion: This case emphasizes the role that weight training plays in the development of VAD in a patient without other known risk factors. This patient’s VAD is suspected to be from neck hyperextension while lifting heavy weights on a bench. Compression of the vessel against the C2 cervical foramina, and at C5-6, where the artery enters the transverse foramina are common sites for mechanical trauma with neck hyperextension and head rotation. The subintimal tears of vertebral artery cause hematoma and a false lumen causing vessel obstruction, thrombosis, and later embolism resulting in stroke. In addition, despite his hospital course, this patient has returned to moderate level of exercise with no residual neurological deficits.

Conclusions: Such cases are important for physicians to identify, as there has been a notable increasing incidence of VAD in patients regardless of risk factors and age due to an increasing focus on physical health. It is also important to note that the signs and symptoms related to VAD are often delayed and pre-date the presentation of ischemic stroke symptoms, in most cases up to fourteen days which can make diagnosis difficult and sometimes missed.