Background: Violence towards healthcare workers represents a critical threat to safe and effective care delivery. United States Bureau of Labor statistics demonstrate disproportionately higher rates of violence towards healthcare staff than workers in other industries, with healthcare accounting for 73 percent of all nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses due to violence in 2018 (1). The bedside care team shoulders a disproportionate share of abusive inpatient behaviors (4-5), which can include verbal abuse, bullying, sexual harassment, and physical assault (2,6-7). Staff who experiencing this abuse suffer significant physical and psychological consequences, including injuries, post-traumatic stress, depression, burnout, increased absenteeism, and higher rates of job turnover (7).

Purpose: Our institution’s policy to respond to disruptive or unsafe behavior historically has included: guidelines for treating underlying medical conditions (such as uncontrolled pain, withdrawal, delirium, etc), addressing psychiatric overlay, assessing capacity/hold status, behavioral codes, trauma-informed care, and reiterating behavioral expectations. However, unsafe behavior may persist, compromising the hospital working and healing environment. Our team quickly learned that interventions to mitigate purely maladaptive coping behaviors were sometimes less successful when no repercussions existed, which in turn greatly imperiled staff safety and wellness. We developed a systematic multidisciplinary approach to addressing unsafe inpatient behavior, unifying prior siloed policies–and ultimately ending in administrative discharge from the hospital if patient medical stability is allows and a pattern of unsafe behavior continues, despite attempts to re-engage the patient in a safe care plan.

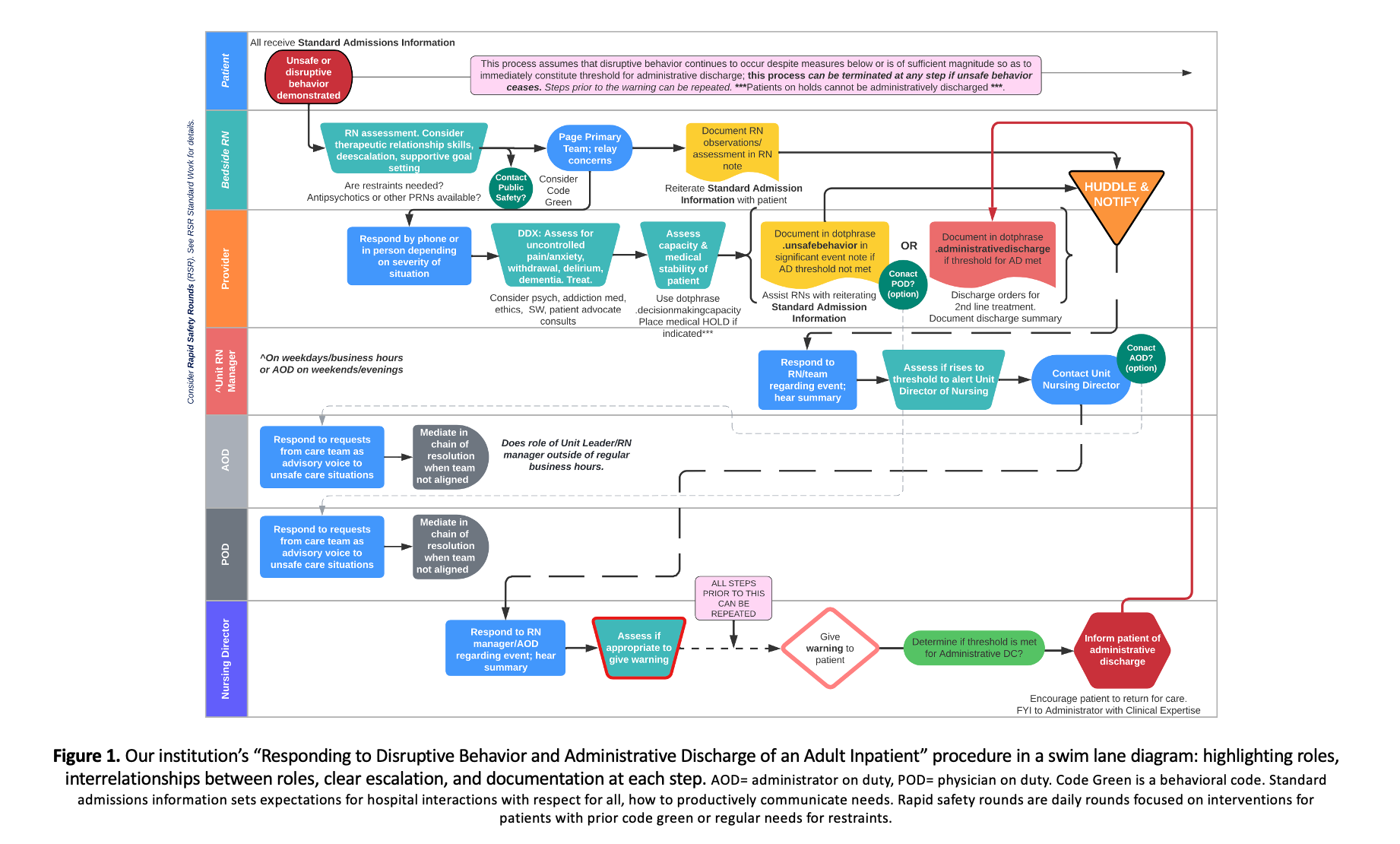

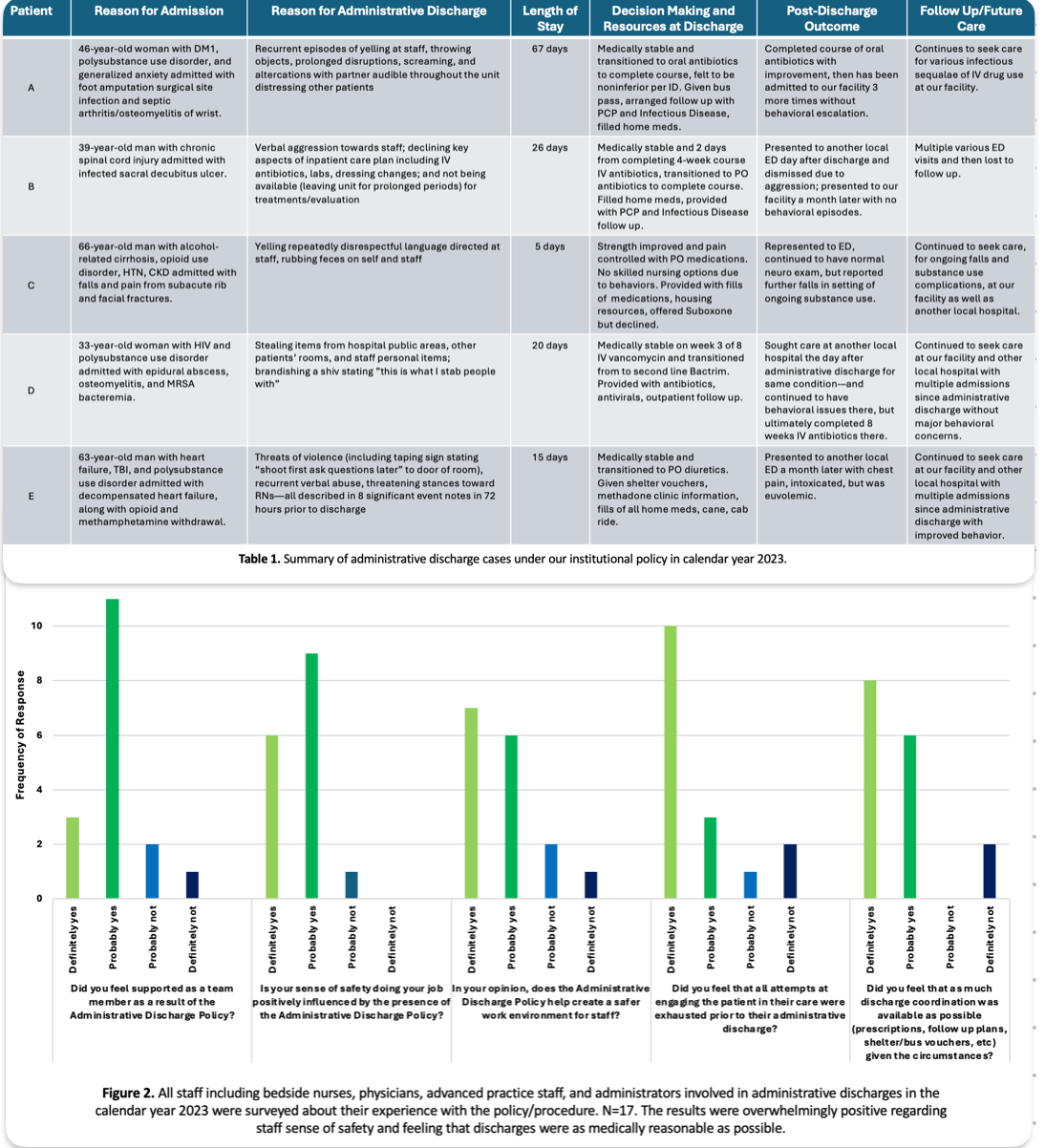

Description: We developed a systematic framework to triage ongoing patterns of disruptive behavior is detailed in figure 1. Our workflow prioritized closed-loop communication, clearly defined multidisciplinary roles and responsibilities, robust documentation, as well as an escalation through administration/nursing leadership for final decision making when unsafe behavior persists. Each of the administrative discharges from our facility during the 2023 calendar year are summarized in table 1 (n=5). Overwhelmingly, these patients returned for care at our facility with future improved engagement, underscoring this policy’s success at boundary-setting while not deterring patients from seeking subsequent care.

Conclusions: • Workplace violence is prevalent in healthcare settings and can lead to negative consequences for both healthcare workers and consumers. • While healthcare teams do our best to mitigate the risk of violence, utilize de-escalation tools, and re-engage patients in their care, administrative discharge can be employed as a last resort for patients who continue to behave in disruptive ways. • Involving hospital administration in the escalation pathway for unsafe behavioral scenarios is an essential element to a successful administrative discharge policy. This permits bedside staff to maintain therapeutic relationships with patients.• This policy was well received by bedside teams; users reported substantially greater sense of safety in their work environment (figure 2). • While administrative discharge is never the ideal outcome of a hospitalization, it is possible to enact this safely and such that the patient feels comfortable returning for future care.