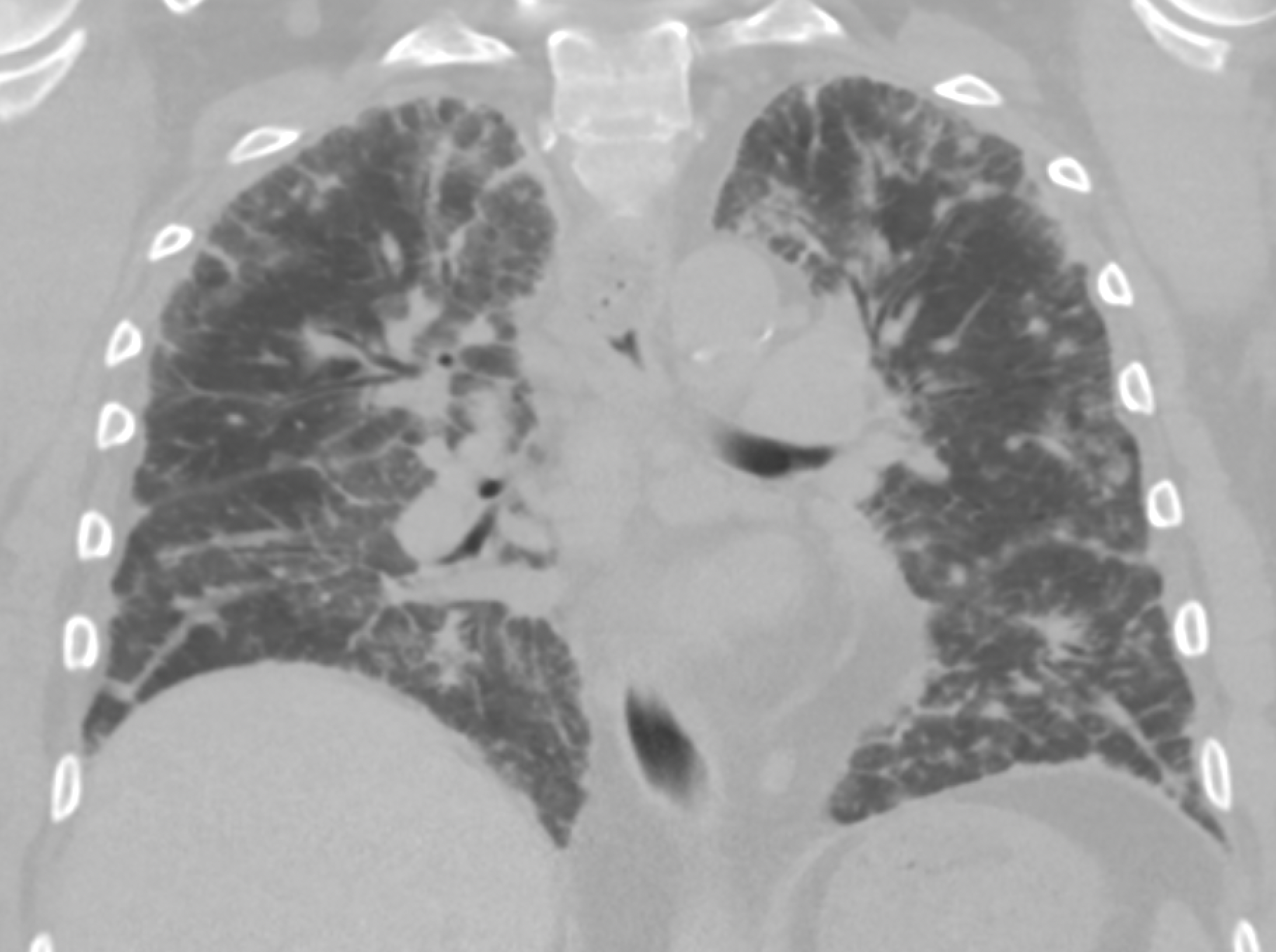

Case Presentation: A middle-aged man with a history of heart failure and atrial fibrillation presented to the hospital with subacutely worsening dyspnea. He had hypoxemia, crackles on pulmonary auscultation, and diffuse airspace opacities on chest radiograph. Admission was requested for presumed exacerbation of heart failure. Upon closer examination, he no edema or elevated jugular venous pressure. There were also no findings to support causes of isolated pulmonary edema such as severe hypertension, uncontrolled tachyarrhythmia, left-sided valvular disease, or myocardial ischemia. A CT of the thorax showed diffuse ground-glass opacities and consolidations throughout his lungs (Fig 1), and evaluation shifted towards causes of infectious or inflammatory pneumonitis. It was noted that he was taking amiodarone at a dose of 600mg daily, initiated during an admission for atrial fibrillation to a local hospital six months ago. Additional results included negative blood and sputum cultures, negative rheumatoid factor and ANA, negative hypersensitivity pneumonitis panel, but a positive C-ANCA at low-moderate titer. The differential diagnosis was narrowed to include amiodarone-induced pneumonitis (AIP), ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV), or atypical infection. Bronchioalveolar lavage was performed which showed lymphomonocytic cellularity with “foamy” macrophages. Microbiologic studies were negative. Amiodarone was discontinued and the patient was initiated on prednisone, which was subsequently tapered over two months. Dyspnea and hypoxemia resolved within several days. At 6-month follow-up, the patient’s symptoms and CT abnormalities had resolved (Fig 2).

Discussion: In addition to the opportunity to review features of AIP (represented typically above), this case demonstrates two important lessons in clinical reasoning. The first is avoidance of anchoring bias. Some features of a case can be powerful anchors in diagnostic reasoning, both adaptively (helping to prioritize likely and common narratives), and maladaptively (subverting consideration of alternate causes). To use appropriate framing while avoiding excess anchoring, it is important to be vigilant to elements of a case that do not fit with a seemingly likely diagnosis. The history of heart failure was a heavy anchor in this case, yet his absent signs of volume overload were a trigger to consider alternate diagnoses.The second is consideration of base rates of disease, not only in the general population, but in the context of a patient’s individual factors. In this case, the most likely diagnoses after initial evaluation were AIP and AAV. While the prevalence of these two diagnoses in the general population is comparable (both 1-10 per 100,000), our patient was part of a unique group of people who take amiodarone. In fact, searching the literature revealed that in those taking >400mg of amiodarone per day, pneumonitis occurs in 20%. Suddenly, the pre-test probability of the two conditions shifts: AAV remains a rare disease, while the pre-test probability of AIP is 20%: orders of magnitude higher. Now, even applying the positive test of the ANCA result – which does have a rate of false-positive results – the post-test probability remains much higher for AIP.

Conclusions: – Careful medication history is critical in the evaluation of hospitalized patients- Amiodarone-induced pneumonitis can present subacutely and resolve with early treatment- It can be helpful to consider base rate of disease not only in general, but also for unique subset of patients