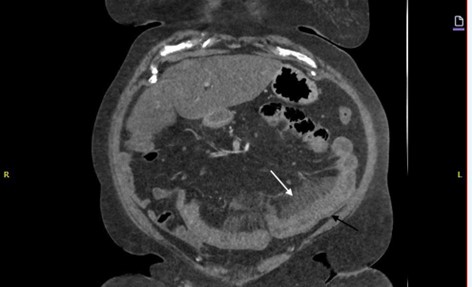

Case Presentation: A 60-year-old Caucasian female with a history of morbid obesity, type 2 diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea presented to the emergency department with chief complaint of a headache. Her blood pressure was elevated, and she was discharged on lisinopril 20 mg daily.Two days later, she returned with severe, diffuse abdominal pain, watery diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Her vitals were stable, and the physical exam showed mild abdominal tenderness without guarding or rigidity. A CT scan revealed small bowel thickening, mesenteric stranding, and reactive free fluid (Figure One). Initial lab work showed leukocytosis at 14.93 (normal- 4.5 to 11.0 × 109/L), elevated hemoglobin at 16.0 (normal- 11.6 to 15 grams per deciliter), and increased hematocrit of 48.5 (normal- 36 to 48%). Electrolytes and stool tests were normal, and EKG showed normal sinus rhythm. These findings support the diagnosis of intestinal angioedema, particularly when coupled with the patient’s symptoms (abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea) and recent initiation of lisinopril. The absence of significant inflammatory markers or other structural abnormalities helps rule out alternative causes, strengthening the case for drug-induced angioedema.

Discussion: ACE inhibitors are prescribed to millions of patients worldwide. About one in three U.S. patients treated for hypertension will receive lisinopril in their lifetime(1). Despite its low incidence, thousands of cases of drug-induced angioedema are expected given the widespread use of ACE inhibitors (2). However, lisinopril-induced intestinal angioedema is likely underreported, with only a few cases documented(3).Intestinal angioedema is often overlooked in practice due to its nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal pain and nausea, which mimic common gastrointestinal conditions, and the absence of hallmark facial or airway swelling. Patients with complex histories, like obesity or diabetes, further complicate diagnosis as their symptoms are frequently attributed to more prevalent conditions, delaying recognition of this rare ACE inhibitor side effect. Diagnostic pitfalls of intestinal angioedema include misattribution of nonspecific symptoms like abdominal pain to more common conditions and misinterpretation of imaging findings, such as bowel wall thickening, as inflammatory or ischemic changes. Additionally, the self-limiting nature of the condition after discontinuing ACE inhibitors often leads to missed or delayed diagnoses(4). In this case, the patient presented with gastrointestinal symptoms after starting lisinopril, and the diagnosis was confirmed by her medication history and CT findings. Lisinopril-induced angioedema should be considered when patients present with similar symptoms after initiating ACE-I therapy.

Conclusions: ACE-I-induced intestinal angioedema is a rare but important diagnosis that can present with nonspecific abdominal pain. Given the common use of ACE inhibitors, clinicians must be aware of this potential side effect and consider it when patients present with atypical gastrointestinal symptoms. This case underscores the need for thorough medication history and evaluation of drug-induced causes of abdominal pain, emphasizing the importance of clinician awareness to improve patient outcomes. Increased vigilance and systematic documentation of ACE-I-induced intestinal angioedema are essential to better understand its incidence and ensure timely diagnosis in clinical practice.