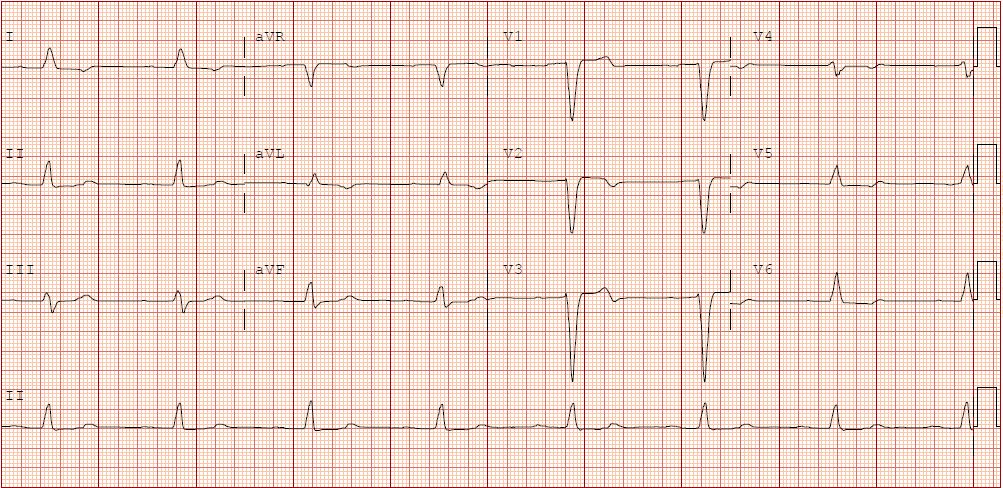

Case Presentation: A 91-year-old male with history of coronary artery disease & heart failure with reduced ejection fraction presented with unresponsiveness. The patient collapsed onto the floor when he came into the kitchen for dinner. His wife could not feel a pulse, so she called emergency medical services (EMS) and started CPR. When EMS arrived, the patient had a palpable pulse, but he was bradycardic to the 40s. He was given atropine with good response to the 60’s but dropped again upon arrival to the hospital. EKG showed first degree heart block & sinus bradycardia. He was obtunded and subsequently intubated for a GCS score of 6. An epinephrine drip was started with improvement of the heart rate. His blood pressure was 154/58 mm Hg, and heart rate was 94beats/min. He normally takes aspirin, atorvastatin, ezetimibe, furosemide, tramadol, etanercept, valsartan, spironolactone, and metoprolol at home. Labs showed potassium of 6.4mEq/L (normal 3.5-5.5mEq/L). BUN 26mg/dl and creatinine were 1.66mg/dl (baseline of 17mg/dl and 0.94mg/dl). Lactate was 3.2mEq/L. Cardiology was consulted who did not recommend inserting a pacemaker. Echocardiogram showed reduced ejection fraction of 45% & regional wall motion abnormalities. Given constellation of findings including hyperkalemia, bradycardia, renal failure and hypotension, the patient was thought to have BRASH syndrome. He was eventually discharged and advised to discontinue valsartan, spironolactone, and metoprolol, with primary care and cardiology follow-up. Subsequent 4-week event monitoring demonstrated no significant bradycardia, arrhythmias or pauses.

Discussion: BRASH syndrome consists of a vicious cycle involving Bradycardia, Renal failure, AV-nodal blocking medication, Shock, & Hyperkalemia(BRASH). It is typically due to the synergy between hyperkalemia & AV-nodal blocking medications, which leads to bradycardia. Because bradycardia reduces the cardiac output, this may impair renal perfusion and cause renal failure, which in turn exacerbates hyperkalemia. If this is left untreated, this cycle may progress to multiorgan failure with shock, bradycardia, & renal failure. Our patient’s presentation may have been triggered by the interaction between valsartan, spironolactone, and metoprolol. Understanding the pathophysiology of BRASH syndrome facilitates a coordinated management strategy that addresses all components of the syndrome. Hyperkalemia should be treated, even if it is mild. Patients should receive iv calcium to stabilize the myocardium, & insulin with dextrose to shift potassium intracellularly. The front-line therapy for bradycardia is intravenous calcium to counteract the effects of hyperkalemia. If this fails to resolve the bradycardia, physicians should have a low threshold to initiate an infusion of epinephrine. If these measures fail, transvenous pacing may be necessary. Fluid status must be assessed individually, based on clinical history & bedside examination. If present, hypovolemia should be treated promptly using a balanced crystalloid.

Conclusions: With increasing numbers of patients being treated for hypertension & heart failure, hospitalists must have a high clinical suspicion of BRASH syndrome in patients presenting with this constellation of findings. Recognizing the syndrome as a clinical entity will help address all aspects of the syndrome &simultaneously address several problems, while minimizing unnecessary interventions & reducing morbidity and mortality.