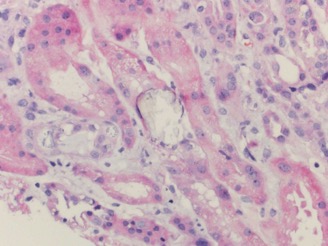

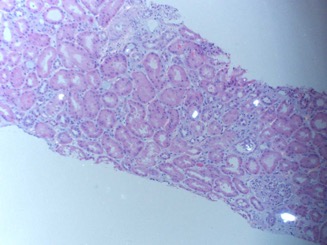

Case Presentation: A 52-year-old male presented with one week of abdominal pain, myalgia, and diarrhea. The patient was referred to our Emergency Department after outpatient testing revealed an increase in serum creatinine to 11 mg/dL from 0.7 mg/dL six months prior.The patient had medical history of hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and former alcohol use disorder. Home medications included amlodipine 5 mg and omeprazole 20 mg daily, as well as sporadic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use not exceeding two grams per day. The patient reported past alcohol use of one to two bottles of wine daily. He stopped consuming alcohol six months prior at the request of friends. In lieu of alcohol, the patient began brewing concentrated iced black tea and drinking over one liter of tea daily.Hospital laboratory data confirmed newly elevated serum creatinine of 11 mg/dL and were otherwise significant for sodium of 127 mmol/L, potassium of 5.5 mmol/L, bicarbonate of 14 mmol/L, and blood urea nitrogen of 93 mg/dL. Urinalysis demonstrated trace hematuria, five white blood cells per high-powered field, and no proteinuria. Renal ultrasound demonstrated increased echogenicity of the kidneys and no hydronephrosis.The patient was initiated on hemodialysis via a central line catheter on hospital day three given his persistently limited urine output and increasing serum creatinine and potassium. He underwent a renal biopsy which demonstrated acute tubular injury, interstitial edema, focal inflammatory cell infiltration, global glomerulosclerosis (Figure 1), and diffuse intratubular calcium oxalate crystal deposition (Figure 2). These findings are consistent with a diagnosis of calcium oxalate nephropathy.The patient’s electrolytes, serum creatinine, and urine output continued to improve following three sessions of hemodialysis. He was discharged off hemodialysis given his improved renal function. He was instructed to stop drinking black tea and to limit other sources of dietary oxalate. His serum creatinine two months after discharge was 1.2 mg/dL at outpatient nephrology follow-up.

Discussion: Calcium oxalate nephropathy results from oxalate crystal deposition in the renal tubules. Kidney biopsy provides a definitive diagnosis, revealing crystal accumulation in the tubules or interstitium. Prognosis is guarded in affected patients, with a majority requiring lifelong hemodialysis. Calcium oxalate nephropathy can be due to ethylene glycol toxicity, enteric hyperoxaluria secondary to malabsorptive conditions such as small bowel resection, genetic errors of metabolism, and overconsumption of oxalate-containing foods. Rhubarb, berries, spinach, beets, cocoa, and tea are foods high in oxalate content. Few case reports have described calcium oxalate nephropathy in the setting of black tea consumption; it represents an uncommon cause of a rare disease.

Conclusions: Making a diagnosis of calcium oxalate nephropathy requires careful history-taking and clinical reasoning. This patient presentation highlights the importance of obtaining a detailed dietary history in the initial evaluation of a patient with acute renal failure.