Background: Accurate attribution of quality metrics to individual hospitalists is crucial for quality improvement and value-based care initiatives. However, the collaborative nature of inpatient care with frequent patient handoffs makes fair attribution challenging. The current understanding of variation in hospitalist quality metrics comes primarily from studies using attribution methods based on who oversaw the majority or plurality of inpatient care.1–3 Meanwhile, many healthcare systems base physician compensation on quality metrics attributed solely to the discharging provider. This study assesses five attribution methods of hospitalist care to directly compare their effects on which patient encounters are included or excluded and resulting hospitalist attributed quality metrics.

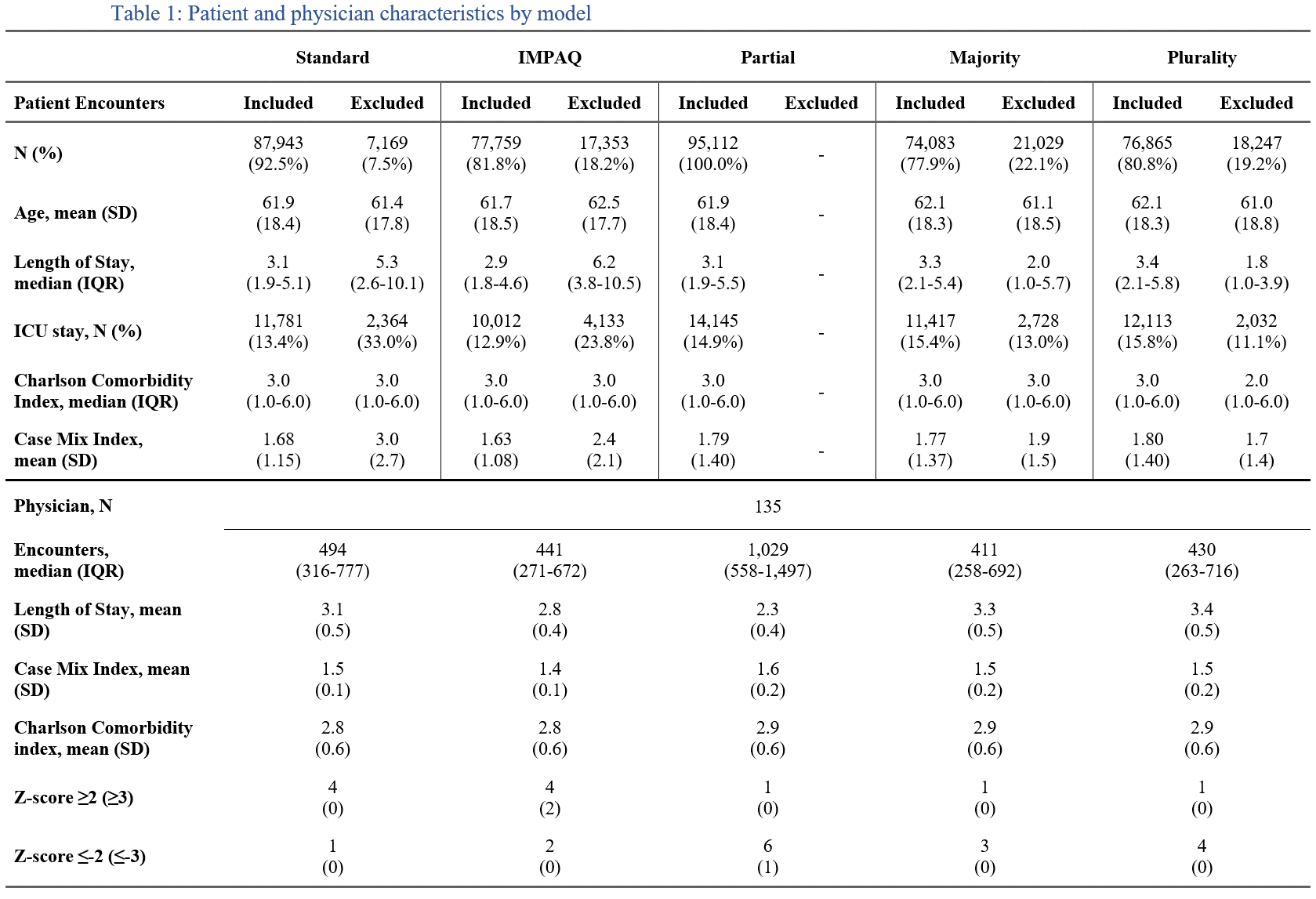

Methods: This retrospective cohort study analyzed all hospital encounters with care from attending hospitalists across five hospitals within Intermountain Health from Jan 2020-Sep 2024. We compared five methods for attributing length of stay (LOS) to individual hospitalists: Standard (discharging physician), Intermountain Method of Provider Attributed Quality (IMPAQ: discharging physician only if they oversee ≥30% of encounter), Partial (proportional day-weighted)4, Majority (physician responsible for ≥50% of stay)1, and Plurality (physician with largest proportion of stay)2,3. Majority/Plurality methods exclude encounters where hospitalists tie for majority or plurality of care. Partial, Majority, and Plurality methods did not exclude encounters discharged from other services if they otherwise met inclusion criteria. Only hospitalist discharged encounters are assessed in a sensitivity analysis. Primary outcomes included correlation in physician quartile rankings between models and identification of outlier performance by z-scores. Secondary outcomes included characteristics of included/excluded encounters and pairwise agreement between methods on included encounters.

Results: A total of 95,112 encounters and 135 physicians met inclusion criteria. Encounters qualifying for individual provider attribution varied from 100% (Partial) to 77.9% (Majority). The IMPAQ method excluded encounters with the longest median LOS (6.2 days), excluding prolonged stays with less individual provider influence. Majority/Plurality methods primarily excluded short LOS encounters (median 2.0 & 1.8 days) due to physician ties, while retaining most prolonged encounters for individual provider attribution. Correlation of physician quartile rankings between methods varied from strong (r=0.93, Majority vs. Plurality) to weak (r=0.27, Partial vs. Standard). The Partial attribution method showed a strong negative correlation (r=-0.70, p< 0.001) between z-scores and percentage of admitting shifts, suggesting influence of attributed quality metrics based on hospitalist shift scheduling rather than variation in practice patterns. The IMPAQ method identified the most profound outliers (4 providers ≥2 SD, 2 providers ≥3 SD). Sensitivity analysis for only hospitalist-discharged encounters yielded similar results.

Conclusions: Attribution method choice substantially influences both the encounters included in quality metrics and identification of hospitalist practice variation. Methods focusing on meaningful physician involvement by excluding prolonged encounters with the least individual provider influence may better isolate variation in individual physician quality metrics.