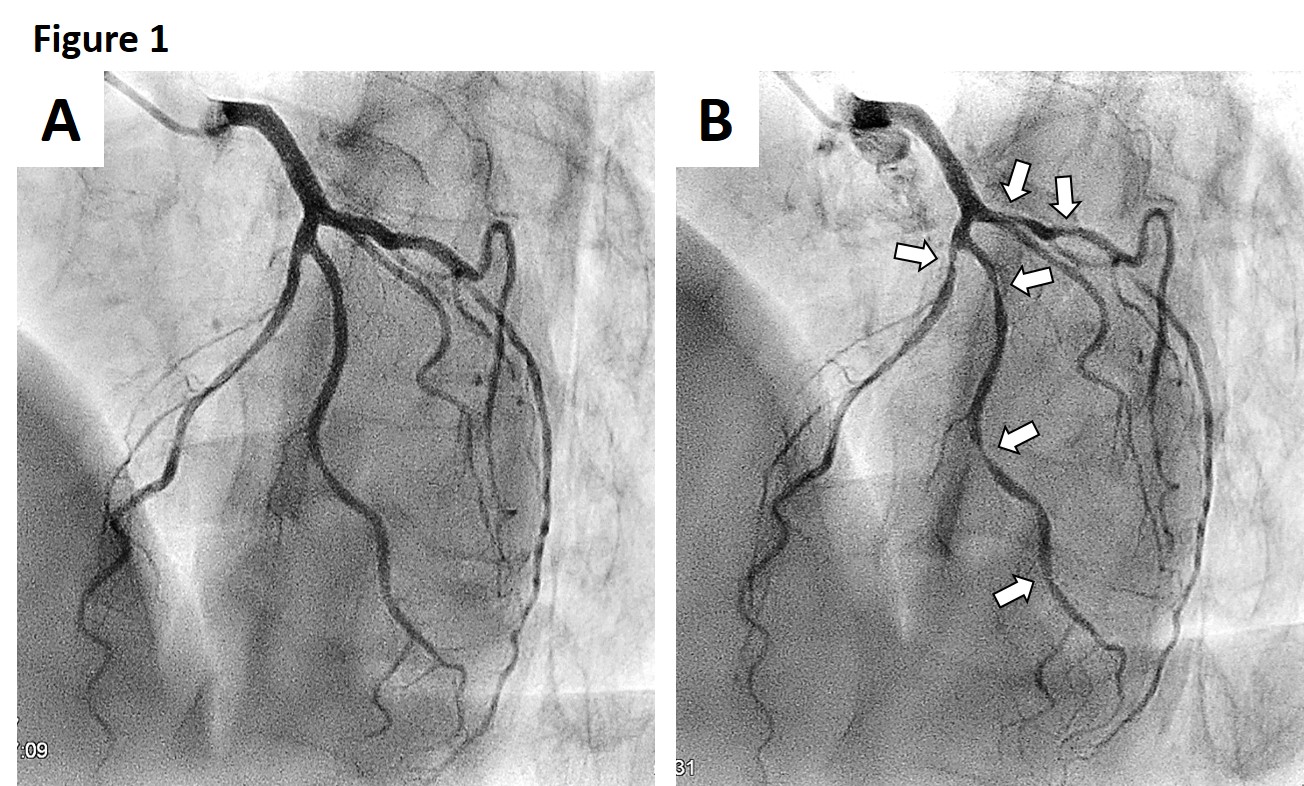

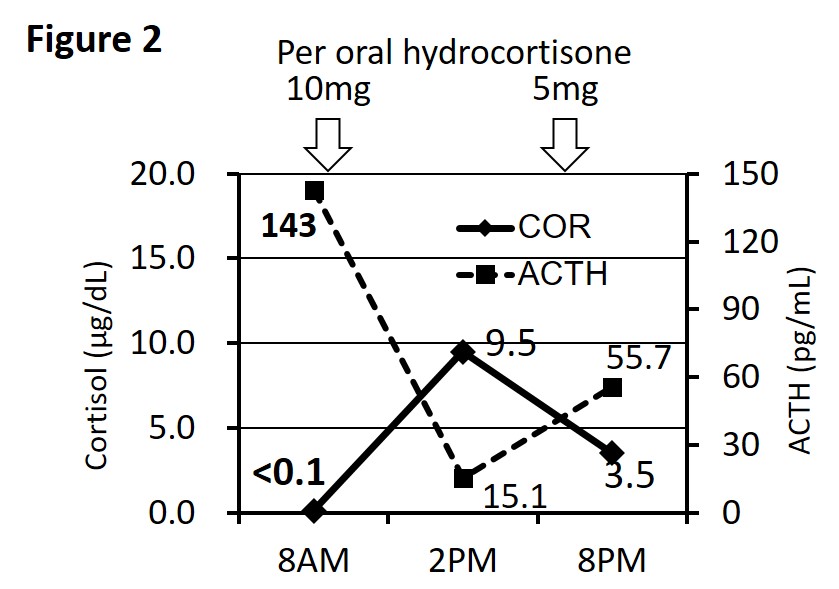

Case Presentation: A 60-year-old man with a history of bilateral adrenalectomy for Cushing’s disease, who received hydrocortisone replacement (hydrocortisone 20 mg/day; 15 mg after breakfast and 5 mg in the afternoon) for 50 years, visited our emergency department with epigastric pain and palpitations. The symptoms manifested without any obvious cause when the patient was at rest and lasted for 1 min. The pain radiated to the left shoulder, accompanied by severe fatigue. Because physical examination, electrocardiogram (ECG), and laboratory tests revealed no abnormalities, he was discharged from hospital. However, his transient palpitations and severe fatigue continued, and he re-visited the outpatient clinic on the following day; he was subsequently admitted to our department. After admission, from midnight to early morning, the patient complained of similar repeated episodes of chest pain that radiated to his left shoulder. Holter ECG showed ST elevation, while the patient experienced chest pain in the early morning. As coronary spastic angina (CSA) was suspected, coronary angiography was performed. Although there was no significant visible stenosis, diffuse spasm of the left anterior descending artery, ST elevations on ECG, and chest pain were provoked after ergometrine administration (Figure 1). Nifedipine and nicorandil were administered, but chest pain and fatigue persisted. Additional tests revealed that the early-morning cortisol level was below detection sensitivity although adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion was increased (Figure 2). As temporal adrenal insufficiency was suspected, dexamethasone 0.25 mg/day was administered, whereupon the early-morning symptoms totally resolved.

Discussion: In patients with adrenal insufficiency, glucocorticoid replacement therapy is mainly administered with hydrocortisone. However, it is very difficult to completely mimic the in vivo circadian rhythm of glucocorticoid levels, and it is known that not only overtreatment but also temporary adrenal insufficiency increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. We presented a case of refractory CSA simultaneously with low early-morning serum cortisol levels. CSA and its attacks are usually well treated and controlled with drugs such as nitrates, calcium channel blockers, or nicorandil; however, 14% of CSA cases are refractory as observed in our patient. Although there have been no reports of CSA associated with adrenal insufficiency, steroids are reported to be one of the available treatment options for refractory CSA. Previous reports showed that the symptoms exhibited by six patients with CSA were relieved after corticosteroid administration. These reports suggest that the CSA spasm may be induced by arterial hyperactivity or allergic angiitis caused by local inflammation, and corticosteroids can suppress the spasm by alleviating inflammation in the vessel wall. Dexamethasone is a potent long-acting corticosteroid that exerts 25-times the potency of glucocorticoid action, compared to hydrocortisone, which could have been effective in suppressing the spastic attacks in our case.

Conclusions: We experienced a novel case of CSA associated with temporary steroid deficiency. Our case intimates that temporal and relative adrenal insufficiency may contribute to the development of coronary vasospasm. Allergic mechanisms may play an important role in spasm development, for which the administration of long-acting steroids is an effective treatment option.