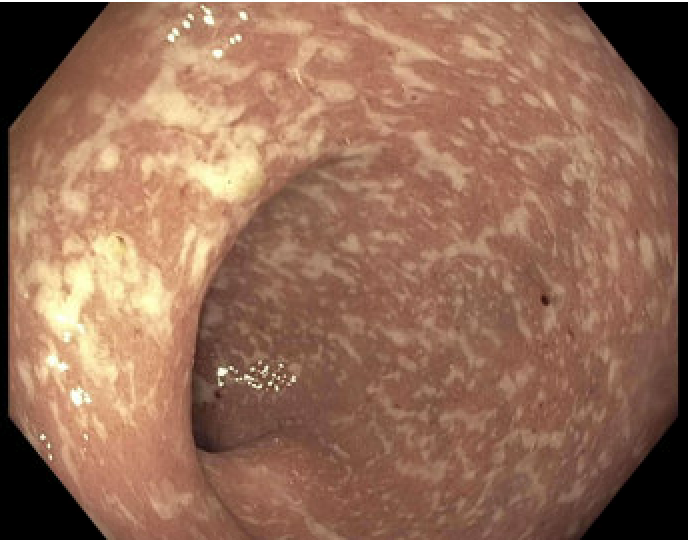

Case Presentation: A 37-year-old female presented to urgent care for one month of bloody bowel movements, approximately 30 each day with accompanying tenesmus, night time accidents, urgency, mild weight loss, and some fatigue. She had no extra-intestinal inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) symptoms, recent travel, antibiotic use, or dietary changes. The labs obtained during the urgent care visit were all within normal limits, including CBC, CMP, ESR and CRP. A plan was made to monitor and manage the patient outpatient. However, one week later, her bloody bowel movements increased in frequency and severity to the point that she was unable to leave her home. Her primary care provider coordinated a direct hospital admission. During the admission, her CT A/P demonstrated significant inflammation in the rectosigmoid colon (Figure 1). Colonoscopy demonstrated 45 cm of Mayo 2 ulcerative colitis (UC) (Figure 2). Pathology demonstrated acute colitis without chronicity. Ulcerative colitis treatment was initiated with prednisone, mesalamine enemas, and PO mesalamine. Patient’s symptoms improved significantly within two weeks. Fecal calprotectin (which resulted after the colonoscopy) decreased from 3000 to 50 μg/g. Patient has a future sigmoidoscopy scheduled to confirm ulcerative colitis pathologically.

Discussion: CRP is an affordable and easily accessible systemic inflammatory marker frequently used in the monitoring and management of IBD. It has also been used in prior studies as a surrogate marker for deep ulcers in ulcerative colitis, and is associated with clinical and endoscopic disease activity (1,2). However, as highlighted by the above case, it may be negative even when patients have true ongoing inflammation. For instance, in a pediatric cohort, approximately 20% of patients with moderate UC disease activity had normal CRP, and approximately 5% had normal CRP and ESR levels (3). Of note, CRP levels are more elevated in Crohn’s disease as compared with UC (4). Finally, CRP levels can be influenced by medications, age, lifestyle factors, and genetic polymorphisms. It is estimated that 15% of health individuals do not mount a CRP response even in the face of inflammation. Our case illustrates that while CRP and ESR values are accessible and affordable first pass indications of inflammation in IBD, they can be misleading and should only be utilized as a piece of a comprehensive IBD work up. With a high clinical suspicion, remarkably unremarkable labs should not delay prompt evaluation.

Conclusions: While CRP is frequently used to monitor IBD, normal CRP levels do not rule out disease. If the clinical picture is consistent with IBD, normal inflammatory markers should not postpone endoscopic investigation as this may result in worsened quality of life and delayed diagnosis for the patient.