Background: As acting interns (or sub-interns), fourth-year medical students are placed in the intern role to develop skills important for internship. At our institution, this has traditionally occurred on inpatient teaching teams that also include residents, interns, and third-year medical students. Because teaching teams are at times crowded with learners, our acting interns have often reported limited patient contacts. In addition, the demand for an internal medicine acting intern experience among fourth-year students was increasing. Also, with rapid expansion of our institution’s hospital medicine division the number of non-resident teams has significantly increased while resident teaching services have remained unchanged, leading many hospitalists desiring more teaching opportunities. For these reasons, we created a non-resident acting intern team composed of one attending and two acting interns. To determine whether similar goals were being achieved in this new model, we compared student comfort level with various intern skills between acting interns on resident and non-resident teams.

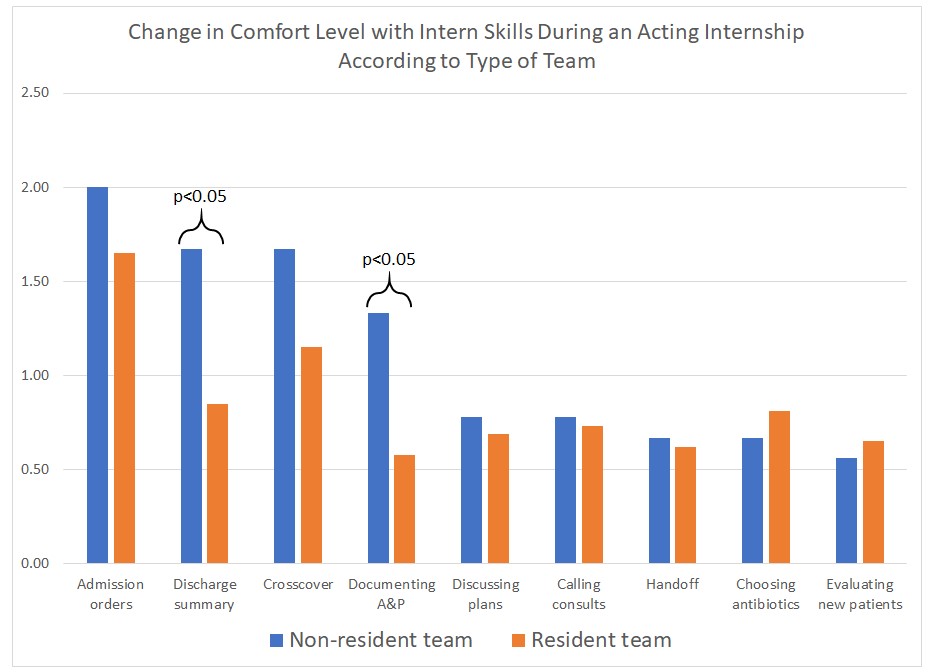

Methods: A pre- and post-rotation assessment tool asked students to rate their comfort level with nine core intern skills: calling consults, documenting assessment and plan, choosing appropriate antibiotics, writing discharge summaries, performing cross-cover, writing admission orders, performing hand-off, evaluating new patients, and discussing plans with patients. All are skills formally expected in the curriculum. Students rated their comfort level with these skills on a five-point Likert scale with 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, and 5=strongly agree. All students enrolled in the course were invited to participate in the surveys anonymously. Pre- and post- responses were paired with a unique identifier to determine the change in each skill for each student. Results from resident and non-resident teams were compared with a t-test.

Results: We surveyed 58 students in the 2018-19 academic year. We excluded 14 surveys due to inability to pair pre- and post- responses or lacking an answer on the team type, leaving 35 (60.3%) paired surveys for analysis. Nine (25.7%) students were on the non-resident team and 26 (74.3%) the resident team. All intern skills improved after completion of the four-week acting internship. Non-resident teams had greater mean improvement in their comfort level with developing an assessment and plan (non-resident 1.33, resident 0.58; p<0.05) and with writing a discharge summary (non-resident 1.67, resident 0.85; p<0.05). Other skills were similar between resident and non-resident teams.

Conclusions: Acting interns on non-resident teams reported greater skill development in two skills and were no worse in any skill compared to acting interns on traditional resident teams. This study supports a non-resident team model as an effective option for acting interns. This model can help offload crowded teaching teams, add additional acting intern experiences, and add teaching opportunities for hospital medicine attendings. Review of narrative comments on student evaluations shows strong support for this model. Since this pilot, we have expanded to a second non-resident team for the 2019-20 academic year.