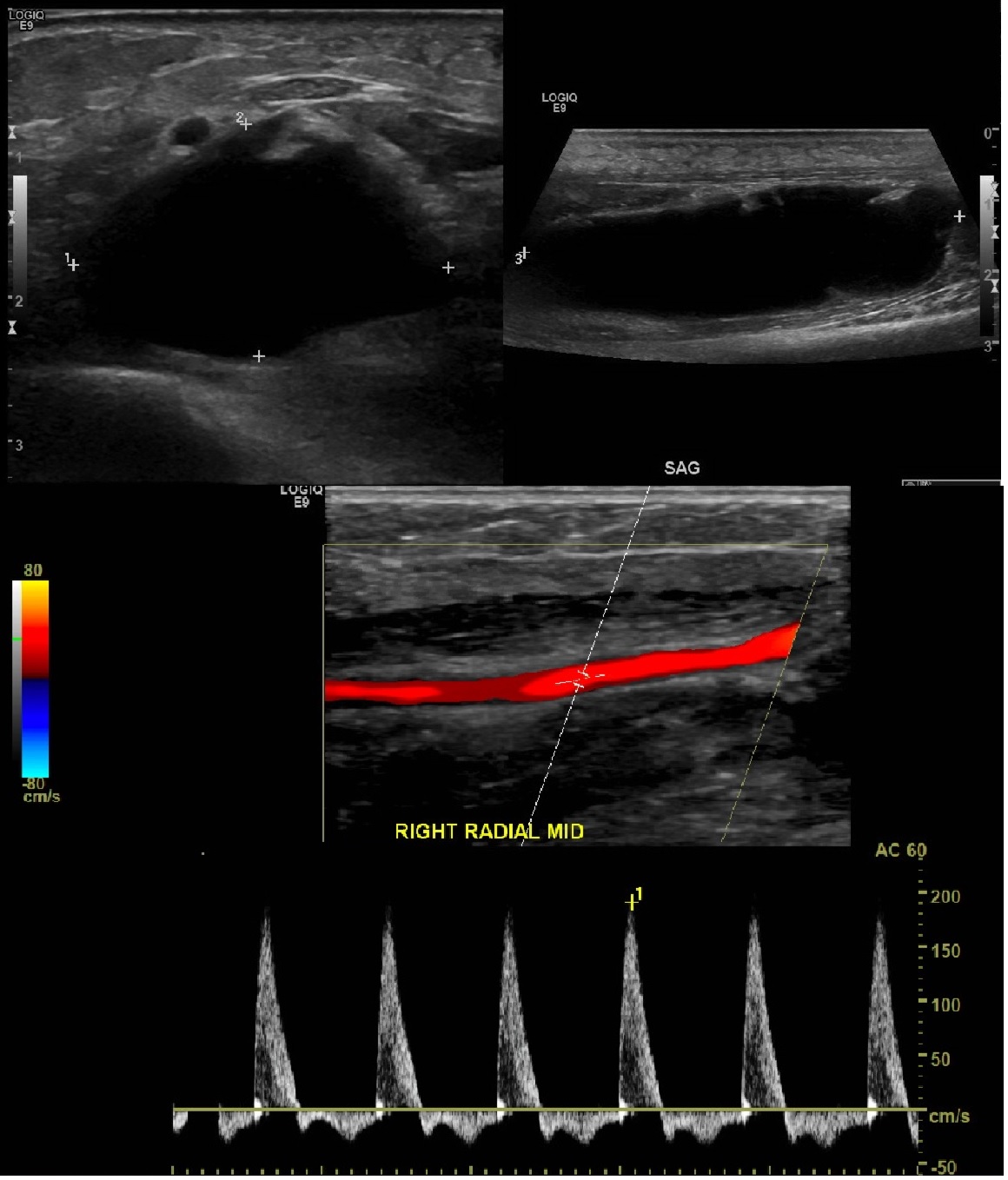

Case Presentation: A 75-year old female with controlled Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Stage 3 Chronic Kidney Disease was admitted to our hospital for anginal symptoms secondary to hypertensive emergency and subsequently diagnosed with NSTEMI. Blood pressure was 206/90 on admission and labs significant for troponin of 0.043 ng/mL that downtrended afterwards. Her symptoms resolved with adequate blood pressure control. Aspirin 81 mg PO daily and heparin drip were started. Right radial angiography was performed with a 6 French catheter sheath without complication. Hemostasis was achieved and TR band was applied. Pulse remained intact afterwards. On the day of angiogram aPTT was at 94.5-96.8 seconds. aPTT maintained at around 73s for the next 3 days. During this time patient also had blood draws from the dorsal surface of the right hand as the heparin drip was infused through the left arm. Daily physical exam only revealed minor bruising on the skin at sites of blood draws and catheterization site. On the third day after the angiogram the patient reported that her right arm felt sore in the morning and warm compresses were applied for comfort. By the afternoon however the right forearm had swollen and the skin was taut on palpation. Patient complained of paralysis, paresthesia, pale color, and increasing pain of the fingers and wrist. Radial pulse was still intact. Heparin drip was stopped. Ultrasound of the right upper extremity was ordered immediately which revealed high velocities in the forearm arteries and a relatively large 6.1 x 1.6 x 2.6 cm predominantly anechoic fluid collection suggestive in the distal forearm/wrist thought to be a hematoma. Vascular surgery was consulted and patient received right arm fasciotomy. Patient was able to have primary wound closure 6 days after fasciotomy with recovery of motor and sensory function of the right forearm. During the recovery process the patient became anemic due to oozing from the wound and due to religious beliefs could not accept transfusion. As an alternative therapy she received ferrous sulfate and epoietin alfa to maintain her hemoglobin level. She was then discharged in stable condition.

Discussion: Radial access for coronary angiography has become preferred because of fewer vascular complications such as major bleeding and ischemic events (1-2). The incidence of compartment syndrome following radial access angiography is 0.004%-0.4% (3). Compartment syndrome after transradial catheterization has been reported mainly as a result of radial artery laceration with presentation beginning hours after the procedure. There is one case where onset of symptoms occurred after four days but were progressive in nature (4). For our patient the onset of symptoms occurred suddenly on the morning of the third day post-catheterization and rapidly progressed within 6 hours. With regards to risk factors, as fitting with Tizon-Marcos et al’s cases, our patient also had reduced creatinine clearance from chronic kidney disease and low BSA at 1.7 m(2) (3).

Conclusions: Compartment syndrome after transradial cardiac catheterization can manifest the same day after the procedure or progress insidiously or in our patient’s case, have rapid onset. Continued vigilance by the patient’s care team and quick intervention is key to keep the disease from causing permanent deficit to motor and sensory functions. It would also be useful to see in the future if aPTT is proportionally associated with the severity of and chance of developing compartment syndrome after transradial cardiac catheterization.