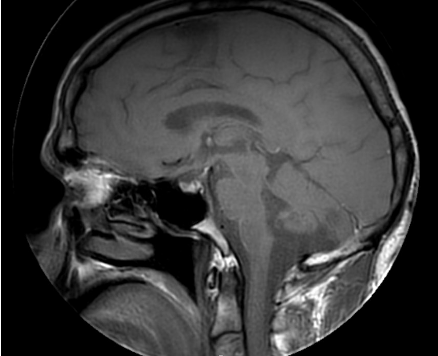

Case Presentation: 47 year old male with left temporal meningioma s/p resection, and recent immigration from India presented with fevers and worsening encephalopathy. CTH was unremarkable however MRI showed leptomeningeal hemispheric, brain stem, and cord signal with perivascular enhancement concerning for CNS TB however included a broad differential. He was started on empiric antibiotics for meningitis and possible TB. Extensive infectious workup with lumbar puncture was negative for infection, including negative AFB for TB. CSF showed mild pleocytosis of 24 and high protein of 285, suggestive of inflammatory process. CSF autoimmune panel resulted positive for anti-glial fibrillary acidic antibody suggestive of GFAP astrocytopathy. He was started on pulse dose steriods. He initially had poor mental status despite multiple days of antimicrobrial therapy however had rapid improvement with high dose steroids.

Discussion: The pathophysiology of GFAP encephalitis is not fully understood but is mainly associated with acute and subacute meningoencephalomyelitis. It is thought that paraneoplastic and autoimmune conditions with T cell dysfunction are frequent triggers. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is a intermediate filament protein in astrocytes, and antibodies targeting GFAP have been identified as a biomarker in autoimmune GFAP astrocytopathy. CNS inflammation is seen with T1 post gadolinium enhancement of GFAP enriched regions with lymphocytic CSF WBC elevation. It presents with heterogenic symptoms thus there are no uniform diagnostic criteria but common clinical manifestations include brainstem symptoms, headaches, encephalopathy, inflammatory myelitis and cerebellar ataxia. GFAP astrocytopathy is described as a monophasic illness with improvement on IV steroids. Treatment usually consists of high dose IV steroids with potential rituximab if no improvement, however steriod-responsiveness is a hallmark of the disease. In these cases, nearly a third of patients have other autoimmune conditions, so further rheumatological and neoplastic screening is recommended. The disease can mimic many other conditions, namely CNS TB. Both of these conditions can present with contrast enhancement, with T2 white matter hypersensitivity. However, the subtle features to compare is the location of enhancement on post-contrast imaging in which radial periventricular involvement can be a key finding in GFAP Encephalopathy compared to more extensive basilar leptomeningeal enhancement in TB. Hydrocephalus can also help differentiate as it is seen more often in CNS TB compared to GFAP Encephalopathy. The GFAP antibody positivity is a strong indicator towards the autoimmune condition, however its absence and a low CSF glucose can point more towards TB and other infectious causes.

Conclusions: GFAP encephalitis remains a challenging diagnosis due to its rarity and similarity in presentation with TB encephalitis. Although the MRI features of GFAP encephalitis may overlap with TB, it is imperative to consider imaging findings in a broader context taking into account symptoms, medical history, and diagnostic findings. The diagnosis and treatment of GFAP encephalitis remains less developed relative to other etiologies of encephalitis however it is paramount to consider this clinical syndrome in the differential as many patients respond to treatment with steroid therapy.