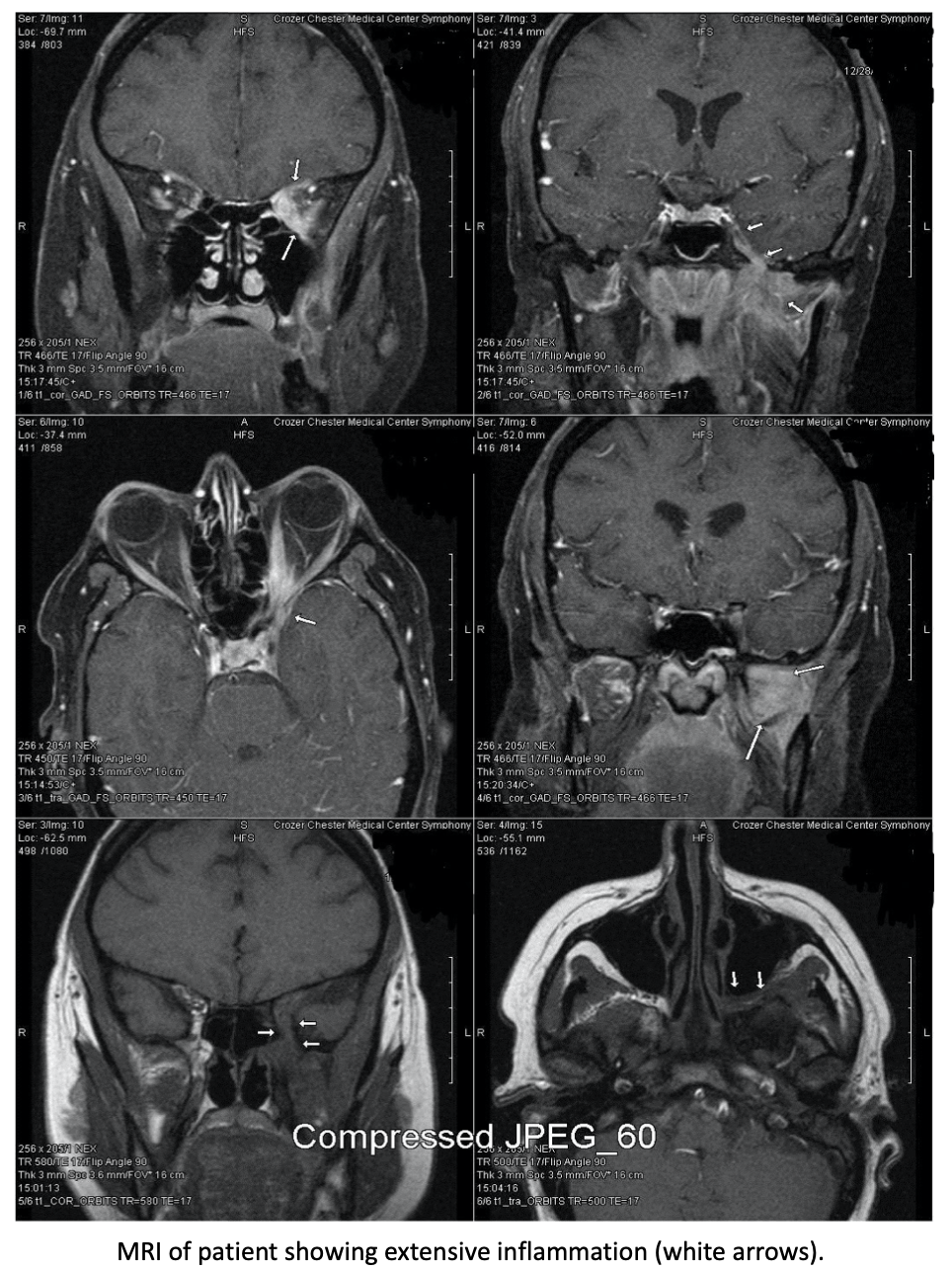

Case Presentation: Gradenigo’s Syndrome, an extremely rare complication of untreated otitis media, is characterized by suppurative otitis media, pain in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve, and abducens nerve palsy (1). Its pathophysiology involves spread of bacterial infection from the middle ear to the petrous apex of the temporal bone and surrounding structures. Untreated, it can progress to meningitis, intracranial abscess, empyema, and so on (1). We describe a rare instance of Gradenigo’s Syndrome leading to unusual complications involving the optic nerve. Our patient, a 50 year old female with type 2 diabetes, fibromyalgia and migraine presented to the Emergency department with 3 months of otalgia, 2 months of hearing loss, 1 month of left-sided blurry vision loss and diplopia, and 3 weeks of deep left-sided facial pain and headaches, all following an episode of otitis media 3 months prior which was treated with Augmentin. Physical exam findings were a significant for visual acuity of 20/20 in right eye and hand motion detection on the left, pupils 6 mm bilaterally, positive afferent pupillary defect on the left, no cherry red spot, no disc pallor, left lateral rectus palsy with double vision and moderate bulge in the left tympanic membrane with moderate effusion. Laboratory findings included leukocytosis of 11.6 x 10^9/L (N:4.8-10.8 g/dl) with 85% granulocytes and elevated CRP of 16.5 mg/dl (N: <5 mg/dl). HbA1c was 6. MRI showed extensive inflammation extending from the left pterygoid musculature to Meckel's cave and left orbital apex with no visible focal drainable fluid collection. She was diagnosed with Gradenigo’s Syndrome, started on IV antibiotics and high dose IV steroids, and her vision gradually improved over the hospital course.

Discussion: Gradenigo’s Syndrome is not seen often in modern medicine since the advent of antibiotics, and more commonly arises in pediatric populations from inadequately managed otitis media (1,2). In this extremely rare adult case, the petrous apicitis spread to involve the left optic nerve, causing visual acuity defects in addition to the classic symptoms. Our patient’s pathologic inflammation may represent a potential consequence of diabetic immunocompromise, as Gradenigo’s Syndrome has been previously described in diabetic patients (3). This case demonstrates the importance of thorough history, physical exam and quick recognition of this symptomatic triad in the hospital setting, especially in the context of additional symptoms such as visual involvement. While rare, the intracranial complications are serious; thus, hospitalists should have a low threshold for MRI, hospital admission, IV antibiotics and steroids, and consultation with both ophthalmology and otolaryngology in a patient with similar presentation. Additionally, this demonstrates the importance of complete history regarding recent primary care visits, as these symptoms may arise in the setting of recent otitis media.

Conclusions: Overall, this case of Gradenigo’s Syndrome represents a rare complication of an even rarer syndrome, but one that is treatable with prompt recognition and action, including but not limited to: admission, low threshold for IV antibiotics and steroids, prompt imaging and specialist consultation.