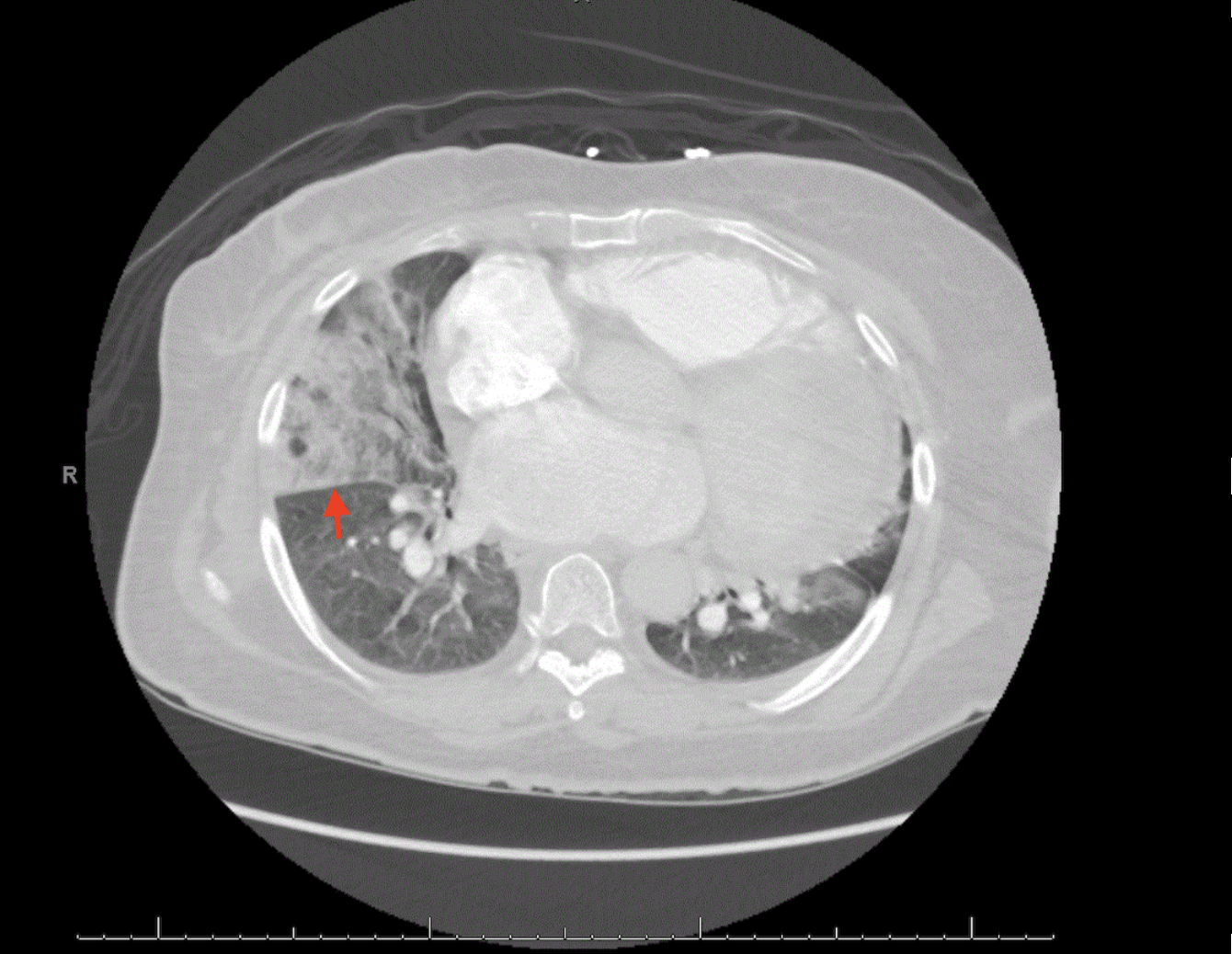

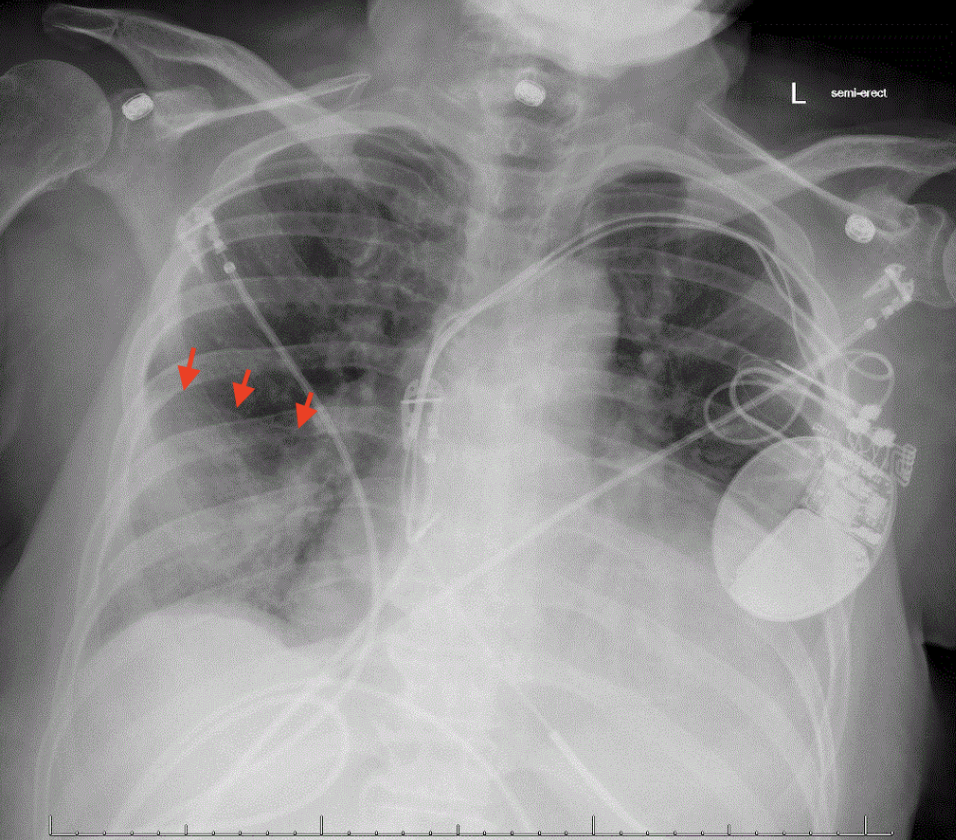

Case Presentation: A 61-year-old female with a medical history of heart failure, hypertension, asthma, and prior history of stroke presented to the emergency department with progressive dyspnea, right-sided chest pain, and increased bilateral lower extremity edema. On presentation, she was hemodynamically stable with blood pressure 138/86 mm Hg, pulse 99 bpm, saturating 98% on room air. Chest x-ray was remarkable for increased infiltrate in the right lung base. Chest CT demonstrated acute right pulmonary emboli involving the right upper and right middle lobe with right middle lobe pulmonary infarction. The patient was consequently started on intravenous heparin. She was not a candidate for thrombolytic therapy or embolectomy as she remained hemodynamically stable and did not have evidence of right ventricular dysfunction or right-sided heart strain on transthoracic echocardiogram. Throughout the patient’s hospital admission, she intermittently required supplemental oxygen (maximum 2 liters) with her lowest oxygen saturation on room air being 91%. The patient was subsequently transitioned to oral anticoagulation and discharged home in fair condition, saturating appropriately on room air.

Discussion: Rapid diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) is critical, and morbidity and mortality decrease with early treatment. PE can lead to pulmonary infarction, which causes tissue ischemia and necrosis. Clinical signs and radiologic features of pulmonary infarction can be nonspecific, making the acute diagnosis a challenge. Chest radiography is often obtained in the work-up of chest pain or dyspnea but has low sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of PE. However, Hampton’s hump, a rare finding on chest radiography, can be a clue that increases suspicion for PE. This finding is characterized by a wedge-shaped opacity in the peripheral lung field associated with pulmonary infarction. This case demonstrated Hampton’s hump, a unique finding on CXR and chest CT associated with pulmonary infarction and PE, first described by Aubrey Hampton in 1940. It has a high specificity (82%), but a low sensitivity (22%) for a PE. Due to collateral blood supply of the bronchial and pulmonary arteries, the lung parenchyma is typically protected from infarction and therefore Hampton’s Hump is uncommon. While pulmonary infarction is not associated with worse outcomes such as hospital readmissions, PE is associated with high mortality if left untreated. Thus, prompt diagnosis and treatment are critical. This case demonstrates how chest radiography, an inexpensive and widely available test, can increase physicians’ suspicion for PE and warrants further evaluation in the appropriate clinical context.

Conclusions: Hampton’s Hump is an uncommon radiological sign of pulmonary embolism that results from a wedge-shaped infarction of the pulmonary parenchyma. It is uncommonly observed due to the collateral blood supply of the lungs. Rapid diagnosis and treatment are critical. Chest radiography is an inexpensive, rapid, and widely available study that can increase practitioners’ suspicion for pulmonary embolism.