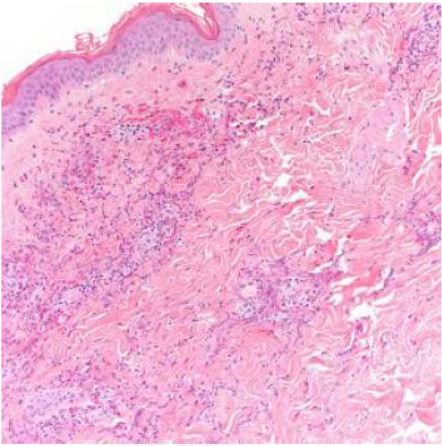

Case Presentation: A 63-year-old man with asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis, and fifty-pound weight loss in the past seven months, was admitted to the hospital for left parietal and right occipital stroke. Asthma was diagnosed in childhood and was well-controlled without recent exacerbation. Patient had focal right hand weakness of 4/5 strength, petechiae on the left lateral thigh, and violaceous plaque on the right lateral thigh that was non-blanching. Work-up for stroke revealed hypereosinophilia and a new non-dilated cardiomyopathy with ejection fraction of 25% and left atrial appendage thrombus. His white blood cell count was 21,600/UL on admission, with an eosinophil count of 12,410/UL (57.5%). Duration of hypereosinophilia was unknown as patient had not seen a doctor for many years. Cardiac MRI was highly suggestive of eosinophilic myocarditis, later confirmed with endomyocardial biopsy. Imaging and labs were not suggestive for other organ involvement. Skin biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with numerous eosinophils but no granulomas. Flow cytometry, genetic mutation analysis, and bone marrow biopsy were all negative for myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms. Immunologic studies were non-diagnostic. Nasal polyp pathology revealed chronic inflammation with numerous eosinophils. Fungal, viral, and parasitic infectious workup were negative. During the hospital course, patient was transferred to the medical intensive care unit for hypotension from cardiogenic shock, complicated by acute kidney injury. Patient was started on high dose pulse intravenous corticosteroids with subsequent decline of hypereosinophilia and near normalization of ejection fraction. However, patient had recurrence of hypereosinophilia with steroid taper. Prednisone was increased to a higher dose and given that patient developed perforated gastric ulcer requiring surgical management as a complication of steroid use, after multidisciplinary discussion, a decision was made to start cyclophosphamide. After the first infusion of cyclophosphamide, patient was discharged home with outpatient hematology, rheumatology, and cardiology follow-up.

Discussion: Hypereosinophilic syndromes (HES) are a rare group of disorders caused by sustained overproduction of eosinophils, leading to eosinophil infiltration and mediator release causing multi-organ damage[1]. Non-neoplastic HES can be difficult to differentiate from disease entities associated with hypereosinophilia (HE) such as eosinophilic granulomatosis and polyangiitis (EGPA).

Conclusions: This case illustrates the difficulty in differentiating the etiology of hypereosinophilia and organ involvement between idiopathic HES and EGPA[2]. Unlike in HES, the precise role of eosinophils in disease complications and clinical manifestations in EGPA remains unknown. Both disorders usually respond to glucocorticoids initially but subsequent treatment strategies can differ. Documented eosinophilic vasculitis on tissue biopsy is helpful in diagnosing EGPA, although early in disease, pathology usually reveals eosinophil tissue infiltration without the distinguishing granulomas and frank vasculitis of late-stage EGPA[3]. For patients with HES and features of EGPA and severe organ involvement who are unresponsive to glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide would be the preferred next agent[4].