Background:

Many patients would like “indication” or diagnosis information included on their prescription labels. Such labeling may increase patient adherence, potentially improving important health outcomes. Additionally, many skilled nursing facilities require that a diagnosis be associated with each medication order before accepting patients discharged from the hospital. Finally, improved communication with patients about their medications may impact favorably on hospital payments through Value Based Purchasing.

Purpose:

To lead a 50+ member Hospital Medicine group at an urban teaching hospital to voluntarily add “indications” to the majority of the new or modified medications they prescribe at hospital discharge. This information attaches to prescription labels as well as to discharge instructions, and persists in the electronic health record (EHR) throughout the life of the prescription.

Description:

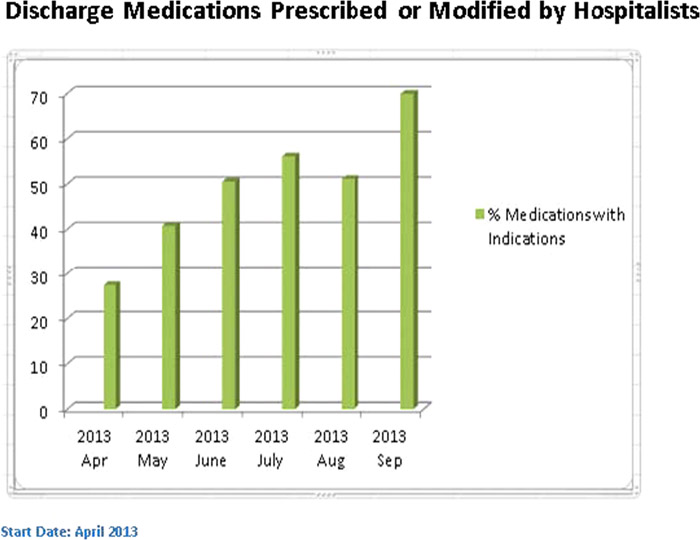

Principal goal was, within 3 months of the start of the campaign, to have indications on 50% of all new or modified medications ordered at discharge by hospitalists. This was achieved, and after 6 months, the rate reached 70%.

The campaign followed Kotter’s 8 step change model.

- 1. We created a sense of urgency at monthly departmental meetings and via email communications. We reviewed: relevant literature; survey results showing that our hospital’s nurses and affiliated‐clinic pharmacists strongly favored indications labeling; and poor “communication about medications” scores on post‐discharge surveys.

- 2. We formed a guiding coalition that included: departmental and hospital leaders; key multidisciplinary hospital committees; and EHR support team.

- 3. We created a vision of change in which Hospital Medicine would take the lead in developing a new, patient‐centered work habit. Typically, this requires two additional mouse‐clicks for each new med ordered at discharge.

- 4. We communicated the vision via monthly email updates to all in the group and to members of the guiding coalition, and in one‐on ‐one communication s with reluctant colleagues.

- 5. We removed obstacles by reminding colleagues that the extra work “up front” creates permanent, accessible information for patients and caregivers; and by engaging EHR support to reduce clutter and simplify choices in the ordering process.

- 6.

Short term wins were documented in monthly email updates, including: graphs displaying team progress; listings of top performers by name; tips for simplifying ordering; and updates on engagement with primary care and EHR Support leaders. - 7.

Building on the change will include: increased advertising of the project; feedback to low performers; and further simplification of orders (to include pre‐selected “default” indications for commonly prescribed medications). - 8.

Anchoring the changes in corporate structure will require continued engagement of primary care and specialty leadership and rank‐and‐file staff, to increase their participation. We will continue to monitor and report hospitalist performance, and the potential exists to “throw the switch” and make the “indications” step a mandatory forcing function in the medication ordering process.

Conclusions:

Through the use of Kotter’s 8 step change model, a large hospitalist group voluntarily improved its communication about medications to patients, colleagues and coworkers, through the addition of indications to the majority of medications they prescribed or modified at hospital discharge.