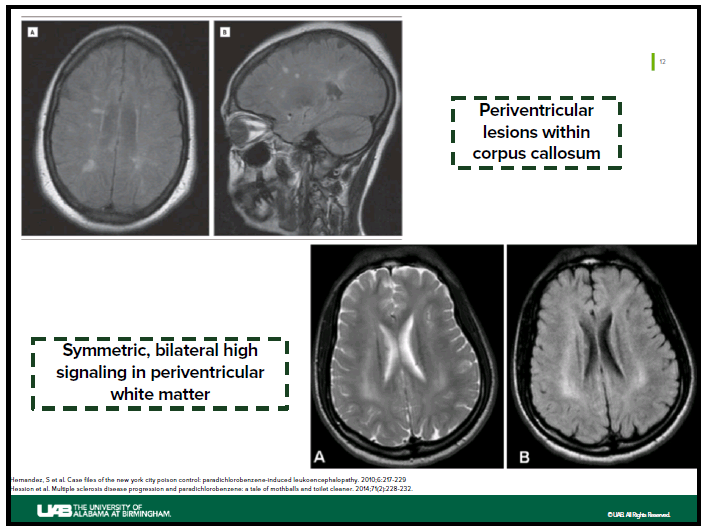

Case Presentation: A 31 year old female with a history of polysubstance abuse was brought to the Emergency Department by family after they noted confusion, weakness, hallucinations, ataxia, vision loss, and bizarre behaviors for 2 weeks along with the patient emitting a pungent odor. Physical exam was notable for a strong odor permeating from her skin, global weakness, confusion, excoriations to the chest and neck, and mydriasis. Ancillary studies demonstrated hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia and microcytic anemia. MRI brain showed cytotoxic lesions of the corpus callosum. After further history, the patient’s family reported that she had been “eating toilet bowl cleaners” for several months. Aggressive fluid hydration, dextrose therapy, 72 hours of n-acetylcysteine, and TPN was started; however, on hospital day 4 the patient was no longer following commands and a repeat MRI brain revealed worsening leukoencephalopathy. EEG monitoring did not demonstrate epileptic seizures. A urine paradichlorobenzene concentration ultimately returned at 1000mg/L (ref: <25mg/L)

Discussion: Paradichlorobenzene (PDCB), an aromatic hydrocarbon, is a common ingredient in mothballs and urinal deodorizer cakes. PDCB can be absorbed via inhalation, ingestion, or dermal exposure, and is stored in adipose tissue due to its high lipophilicity. PDCB is further metabolized by the CYP450 systems to an inactive metabolite. Both neurotoxicity and withdrawal symptoms have been described in case reports. Other clinical manifestations include hemolytic anemia, acute hepatitis, dermatitis, renal failure, and pulmonary granulomatosis. Neurotoxicity after PDCB exposure may manifest as psychomotor slowing, dysarthria, ataxia, amnesia, vision loss, peripheral neuropathy, cognitive decline, and coma. Of note, a “coasting” phenomenon has also been documented presumably due to the lipophilic nature of PDCB causing it to be slowly released from adipose tissues, which may prolong clinical improvement after cessation of initial exposure. This is particularly notable when starvation is present, as faster mobilization of fat reserves occurs – suggesting that both acute and chronic toxicities can occur. Another case report hypothesized that abrupt withdrawal from PDCB can also manifest with severe neurologic decline with catatonia and MRI findings of demyelination and axonal loss. Management of neurotoxicity secondary to PDCB exposure is limited. All case reports note some degree of cognitive decline although time courses for symptom manifestations and clinical improvement were variable. Most patients had complete resolution of symptoms within 3 to 6 months, while for some patients symptoms persisted. It remains unclear if time to recovery and severity of neurotoxicity depends upon duration of exposure or total body burden of PDCB. Reducing agents such as n-acetylcysteine, dextrose to prevent adipose tissue mobilization, and lipid therapy to bind up PDCB have been theorized but no current high level evidence supports their use.

Conclusions: With the increased incidence of creative drug use, physicians should be adept in identifying PDCB toxicity. Exposure to high concentrations of PDCB can cause a variety of symptoms, most notably neurotoxicity. The time courses for symptom manifestation and clinical improvement can be variable. There are no known proven effective antidotes for PDCB neurotoxicity. The goal of treatment is reduction of exposure along with supportive care.