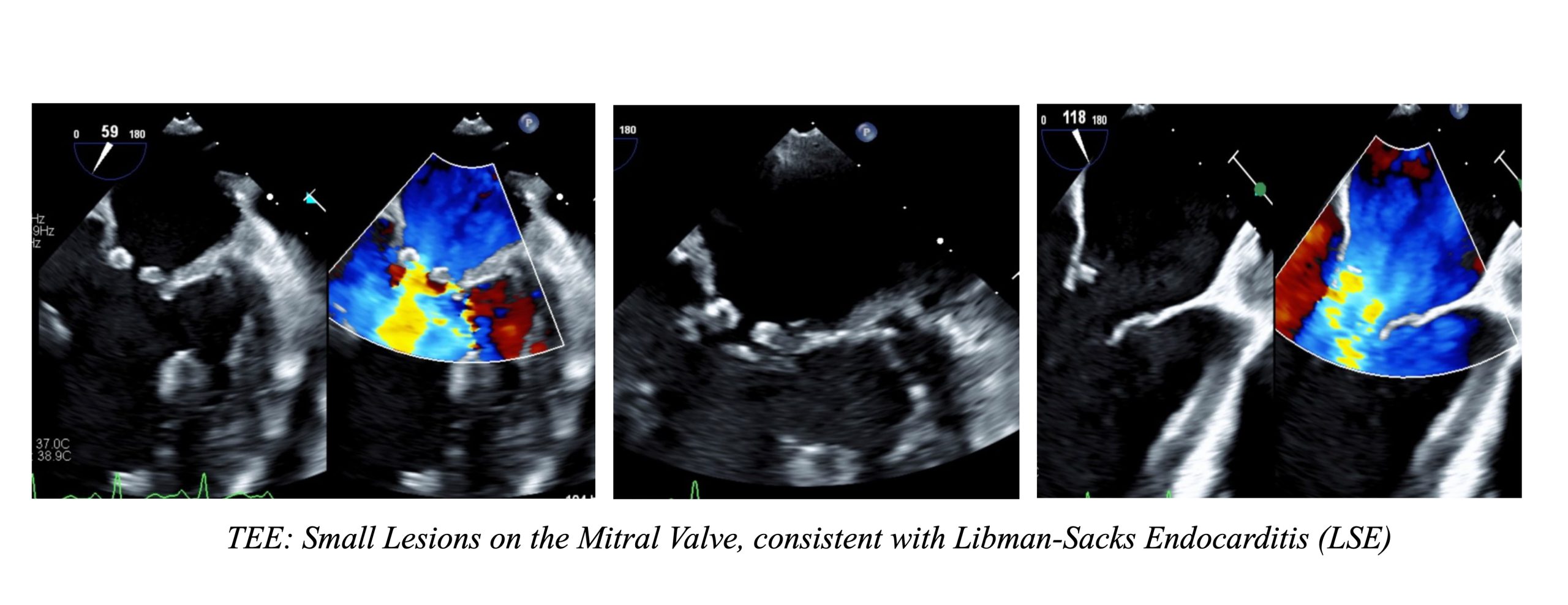

Case Presentation: A 25-year-old female with a history of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), lupus nephritis, cardiomyopathy, transient ischemic attack, and epilepsy presented as an ICU transfer for Altered Mental Status (AMS). The patient initially presented to an outside hospital for this complaint, which was attributed to seizures. Her course was complicated by severe hypotension, again believed to be precipitated by seizures, leading to cardiac arrest. Following the return of spontaneous circulation, she was transferred to our institution due to undifferentiated shock and ongoing encephalopathy. At the time of admission, CT head and EEG were negative. MRI brain showed multifocal punctate lesions. Cardiac MRI and Transthoracic Echocardiogram (TTE) revealed no valvular vegetation. An infectious workup came back negative. Meanwhile, the patient’s AMS continued to improve, and she was transferred to the general medical floor under hospitalist care. A repeat MRI after five days showed persistent Diffusion-Weighted Imaging hyperintensities in bilateral border zones and bilateral cerebellar hemispheres. At this point, neurology was consulted given concern for stroke. Transesophageal Echocardiogram (TEE) was recommended to rule out endocarditis. TEE showed small, fixed masses on the mitral valve consistent with Libman-Sacks Endocarditis (LSE). Cardiology was consulted and the patient was started on heparin for anticoagulation.

Discussion: This case highlights the rare occurrence of LSE and the essence of a multidisciplinary approach in patient care. It also emphasizes the need for hospital medicine providers to be vigilant of anchoring bias, continually reassessing initial diagnoses and pursuing additional workup if warranted. LSE is a non-infectious endocarditis characterized by the deposition of sterile platelet thrombi on heart valves. It is a rare condition that is often discovered during autopsies, with prevalence rates from 0.9% to 1.6%. Vegetations associated with LSE can dislodge, posing a high risk of systemic embolism. TEE is the most sensitive imaging for detecting small lesions related to LSE. Treatment involves systemic anticoagulation and addressing the underlying cause, such as malignancy or SLE itself. For our patient, a key diagnostic challenge was distinguishing between the various mechanisms contributing to the patient’s condition. Her presentation was initially attributed to postictal changes after seizures. Even the initial MRI results were attributed to hypoxic brain injury following cardiac arrest, and neurology has signed off. However, a repeat MRI five days later showed persistent multifocal infarcts, raising concern for embolic phenomena. This finding prompted further evaluation for other causes of multifocal stroke, including a second neurology consultation and an ischemic workup. TEE was obtained due to its higher sensitivity compared to TTE and cardiac MRI, both of which already resulted negative. TEE revealed small lesions on the mitral valve, which confirmed the diagnosis of LSE in the setting of multifocal infarcts and negative blood cultures.

Conclusions: In complex multi-organ cases, rare diagnosis can be easily overlooked. With multiple care teams involved in a patient’s long hospitalization, anchoring bias can lead providers astray. However, by maintaining a broad differential and adopting a stepwise and critical approach, we were able to identify a rare condition like LSE.