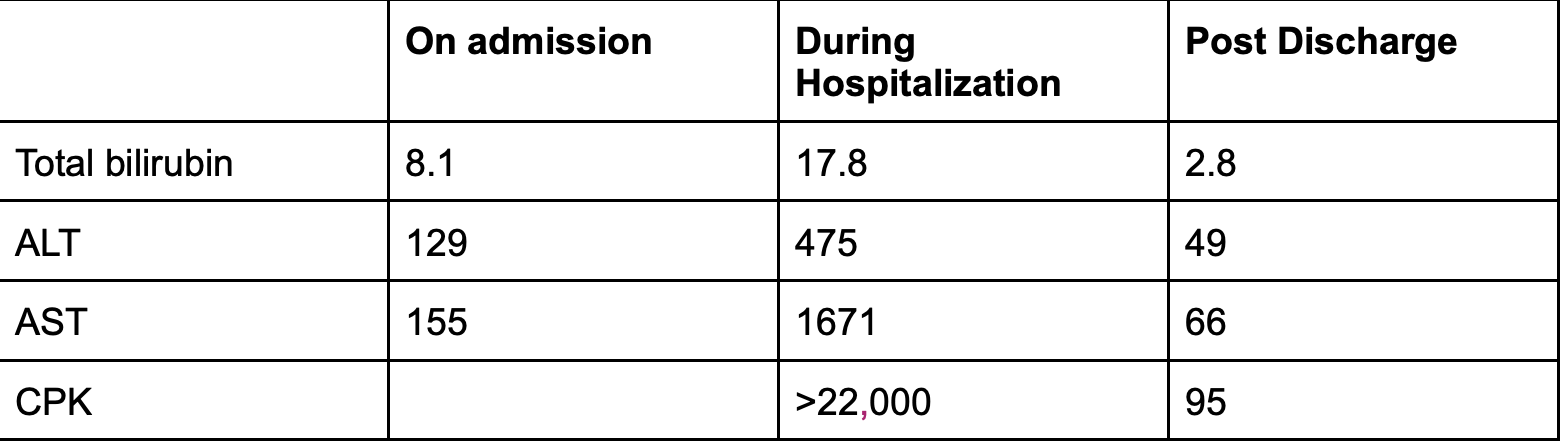

Case Presentation: A 40-year-old man with history of hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and alcohol-induced liver cirrhosis complicated by portal hypertension, ascites and esophageal varices presented with three weeks of epigastric abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. The Physical Exam was unremarkable. Lab results showed elevated Lipase 1854 U/L, Tbili 8.1 mg/dL, Dbili 5.5 mg/dL, ALT 141 U/L, AST 164 U/L, and AKP 305 U/L consistent with pancreatitis and worsening liver injury. He was admitted with resumption of his home medications including atorvastatin 40 mg daily (initiated one month prior). During his hospital course he had progressive increase in bilirubin level up to 14.5 mg/dl. However, Imaging was not consistent with choledocholithiasis or CBD dilation.On day six, the patient reported bilateral thigh pain and weakness. Physical examination revealed bilateral muscle tenderness with reduced strength throughout. Labs were notable for creatine phosphokinase over 22,000 U/L and ALT of 475 U/L. Despite severe rhabdomyolysis, renal function remained stable. Patient also reported he was unsure whether he was taking his statin at home. Statin therapy was discontinued, and the patient received intravenous fluids. CPK level began to decline within 8 days of discontinuing statin therapy.

Discussion: Liver injury and rhabdomyolysis are known sequels of statin therapy. Patients with existing liver impairment may be at elevated risk with statin use, due in part to impaired metabolism of statins by CYP3A4 enzymes. Previous guidelines have therefore recommended approaching statin therapy in patients with liver disease with caution. Agents not primarily metabolized by the liver, such as pravastatin and rosuvastatin, are generally preferred over atorvastatin due to lower theoretical risk of elevated levels of circulating statin and injury.Recent literature however, including multiple RCTs have shown various benefits of statin in patients with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Specifically reducing the risk of cirrhosis in patients with chronic liver disease, preventing decompensation in cirrhotics, and reducing all-cause mortality. This is likely mediated by non lipid lowering effects of statins including reduction of oxidative stress injury, beneficial effects on endothelial function via a nitric-oxide synthase pathway, and reduced inflammatory cell activation.

Conclusions: Although, patients with cirrhosis may be at increased risk for statin-induced liver injury, evidence suggests benefits from statins beyond lipid-lowering effects. These non-lipid-lowering mechanisms may slow or prevent disease progression. While caution is advised, statin therapy should be considered for these patient populations. To minimize risk, gradual initiation, close monitoring, and the preference for non-hepatically metabolized statins are recommended.