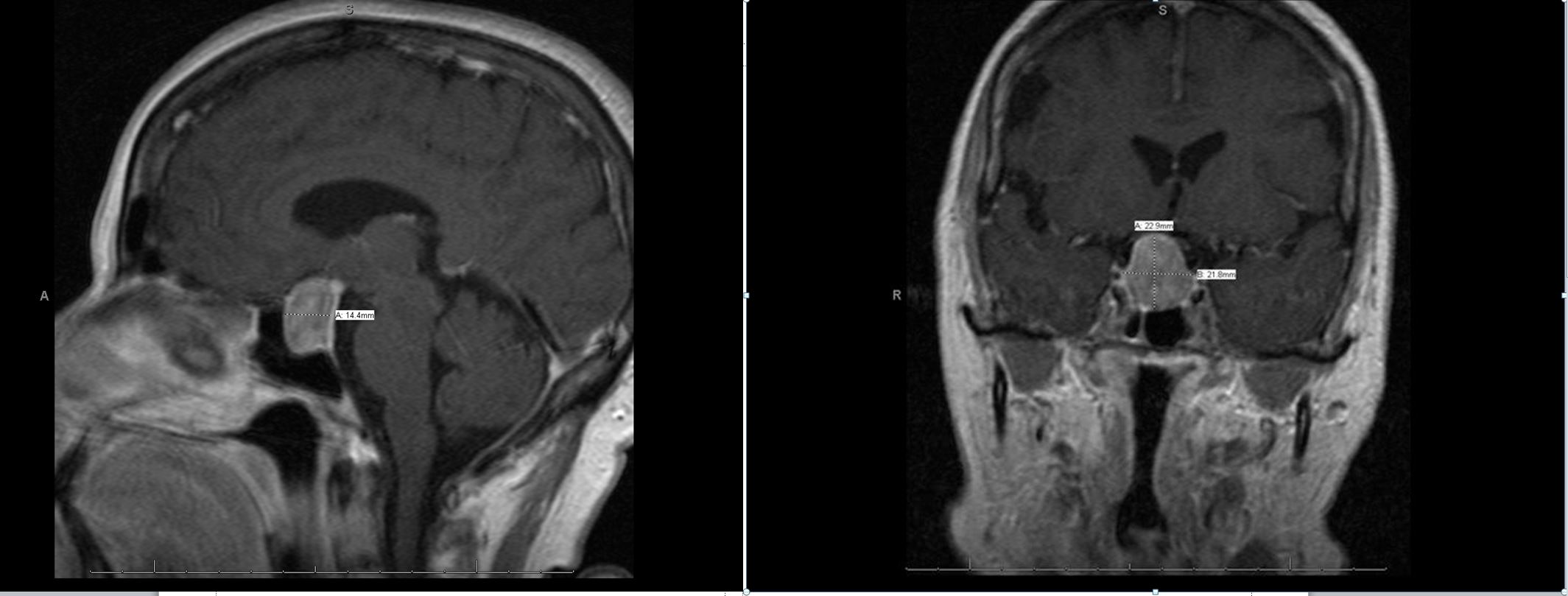

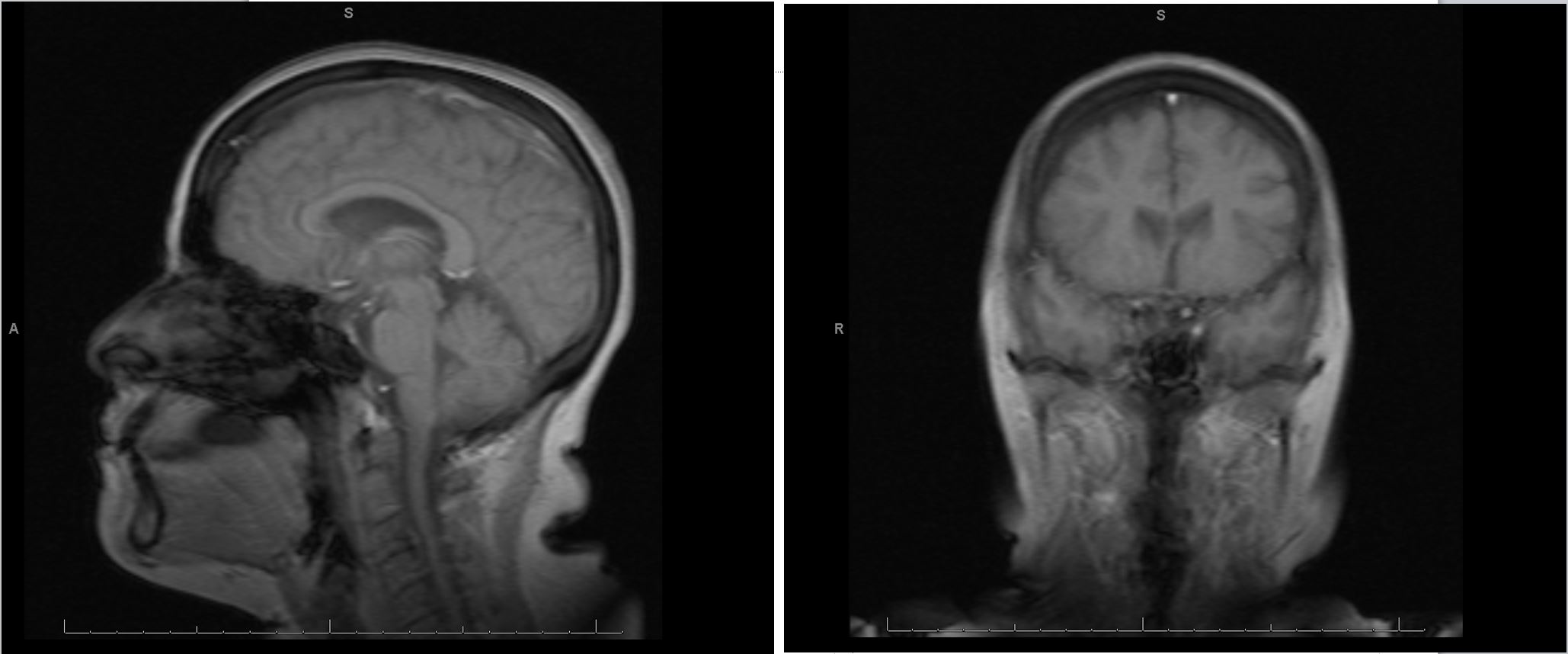

Case Presentation: A 60 year old female with past medical history of chronic migraines presents with chief complaint of nausea and vomiting, with associated headache and malaise. She reports recent emergency room visit two weeks prior at an outside hospital for a “cold” with stomach pain. She was told she had a urinary tract infection and prescribed metronidazole, clarithromycin, lansoprazole, ondansetron, nitrofurantoin, and dicyclomine. She took one dose of each medication and then experienced worsening nausea and vomiting that lead to inability to tolerate oral intake. She appeared to be a poor historian, but a language barrier complicated communication. The patient was afebrile with stable vital signs, and had an unremarkable physical exam. She was admitted for severe hyponatremia (119 mmol/L) and hypokalemia (3.1 mmol/L). She was treated with a normal saline infusion. Her sodium corrected and maintained at 122mmol/L for 24 hours. She then received a total of 60mEq of oral potassium. After additional IV hydration and improved oral intake, her sodium normalized within two days. Her symptoms improved but she had a lingering headache that was worse in the mornings, which she reported was similar to her longstanding migraines. The cause of her hypovolemic hyponatremia was attributed to dehydration due to an acute viral illness.The patient appeared medically ready for discharge but her initial workup noted a low TSH and low T4. A subsequent T3 was within normal limits. A morning cortisol level was indeterminate for adrenal insufficiency. Via interpreters, the patient originally denied vision changes with her headaches but when asked by a physician fluent in her primary language, the patient specifically reported peripheral vision loss. An MRI brain found a pituitary macroadenoma pressing on the optic apparatus. Neurosurgery, endocrinology, and ophthalmology evaluated the patient. She was started on levothyroxine for secondary hypothyroidism, and her workup found the patient had a non-secretory pituitary adenoma. The patient was discharged, and had an outpatient transsphenoidal adenomectomy. On follow-up, she had no apparent complications with return of normal vision.

Discussion: Pituitary adenomas occur in 10% of the population, most are incidentally found on imaging. Only one in 1000 is clinically significant to require treatment. Non-secretory adenomas destroy normal pituitary tissue as they grow leading to hypopituitarism. Transsphenoidal surgery is first line treatment for most pituitary adenomas. For this patient, her pituitary macroadenoma was nearly missed. Common signs and symptoms of pituitary adenomas are similar to viral illnesses—stomach pain, poor appetite, nausea/vomiting, headache, dizziness, and fatigue. While this patient felt better after treatment for hyponatremia, it was important not to anchor the diagnosis to poor oral intake from a viral illness. Adding to the diagnostic confusion was inconsistent communication attributed to language and cultural barriers. Even when using certified medical interpreters, context can be lost in translation. Miscommunication can be deadly. Careful attention to phrasing, cultural cues, and health literacy improves communication and trust between providers and non-English speaking patients.

Conclusions: Miscommunication can be deadly. Overcoming language and cultural barriers increases communication and patient trust in providers. Clinical symptoms of pituitary adenomas are similar to other conditions, so adequate communication is key.