Background: One in five Americans (64 million) speak a language other than English, and one in twelve Americans (26 million) speak English less than “very well”, classifying them as having limited English proficiency (LEP). LEP patients have difficulty navigating the healthcare system due to language barriers in understanding their treatment plans, communicating with providers and other challenges resulting in lower quality care and disparate health outcomes. Using professional interpreters when communicating with patients with LEP has been shown to improve outcomes. In this study we sought to determine barriers for hospitalists in accessing and consistently using professional interpreters.

Methods: Baseline data was collected from our 600-bed academic medical center’s Interpreter Services vendor as well as from the electronic medical record from July 2018-April 2019 on the daily census of patients with LEP on the hospital medicine service. LEP was defined as patients reporting needing an interpreter or whose preferred language was not English. We also extracted data on video interpreter use, the only form of interpretation reliably documented and tied to individual patients and providers. We sent an electronic survey to faculty hospitalists asking about use and barriers of using professional interpretation.

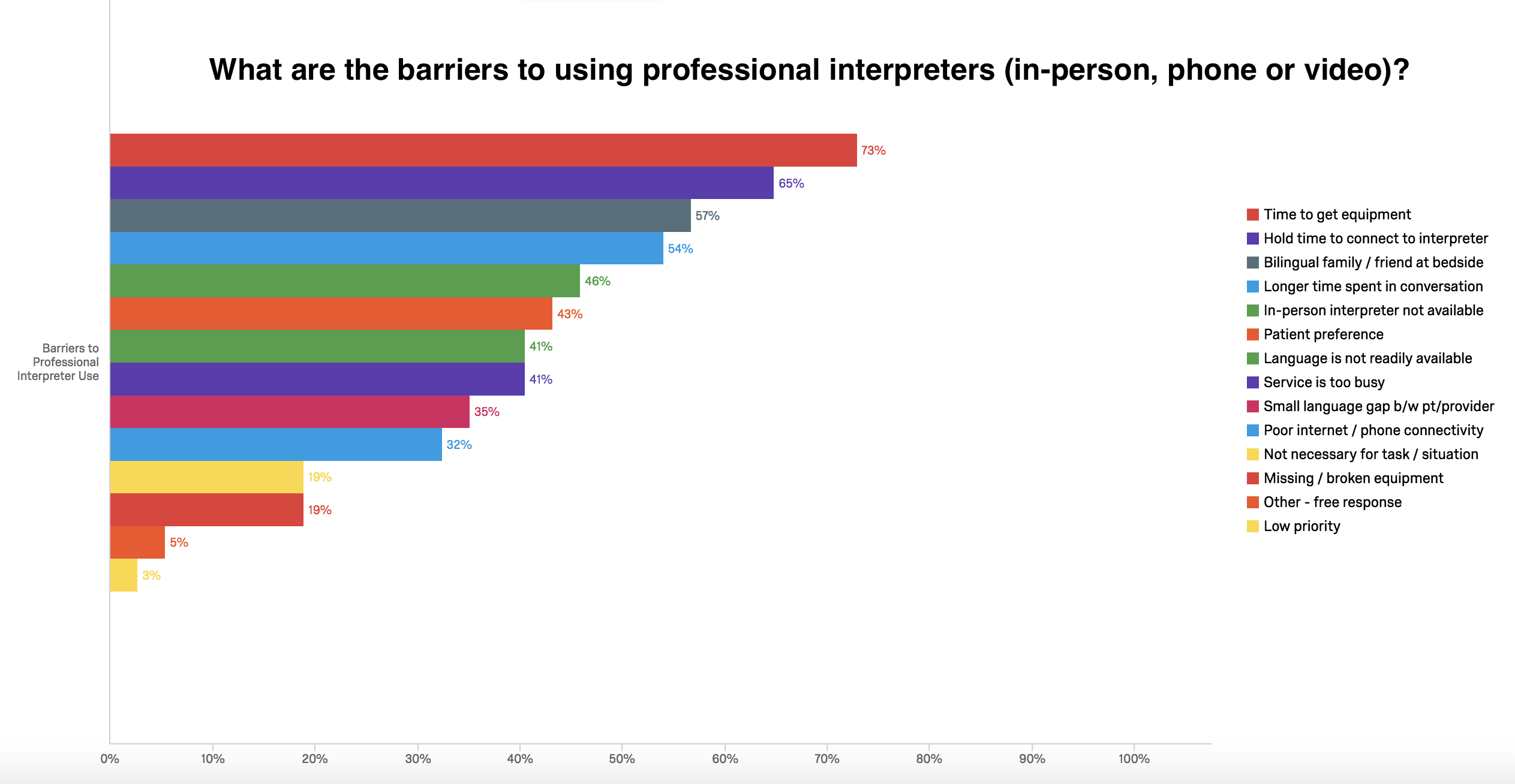

Results: Out of 112 admitted patients that qualified as LEP during August 2018, 23 (20.5%) of patients were on the hospital medicine service. A previous study captured a baseline of 18% for hospitalized patients that qualified as LEP. During the time period of the study, among the 8635 hospitalization days of LEP patients, physicians on the general medicine service used video interpreters on only 2321 (26.9%) of hospital days. We sent 74 surveys to hospitalists and 48 were completed (65% response rate). Out of the various interpreter services available (video, telephone, and in-person), hospitalists reported using video the most commonly. Seventy-nine percent of hospitalists reported barriers in speaking with their LEP patients and 74% described their care of LEP patients as worse than their care of English-speaking patients. The most commonly reported barrier to using professional interpreter services was the time required to arrange interpreting services (Figure 1).

Conclusions: Our study found that patients with LEP communicated with their primary hospital medicine physician using a video interpreter on only 26.9% of hospital days. The amount of time required to obtain an interpreter was the most commonly reported barrier. These data can help inform future interventions designed to improve communication with patients with LEP.