Background: Microaggressions, defined as verbal or non-verbal communications that convey hostility, invalidation or insult based on an individual’s marginalized status in society, are ubiquitous and harmful in health care and medical training. They occur between and among patients, families, and interprofessional providers of all levels. Prior work has shown that microaggressions can pollute the clinical learning environment by increasing depression and anxiety, lowering self-esteem, impeding productivity and problem-solving, and creating a hostile work environment. Microaggressions are difficult to respond to, especially for medical trainees who are trying to maintain a therapeutic alliance, balance principles of medical ethics, and negotiate professional hierarchies.

Purpose: To provide internal medicine residents with practical training on how to recognize and respond to microaggressions from patients and other clinical care team members.

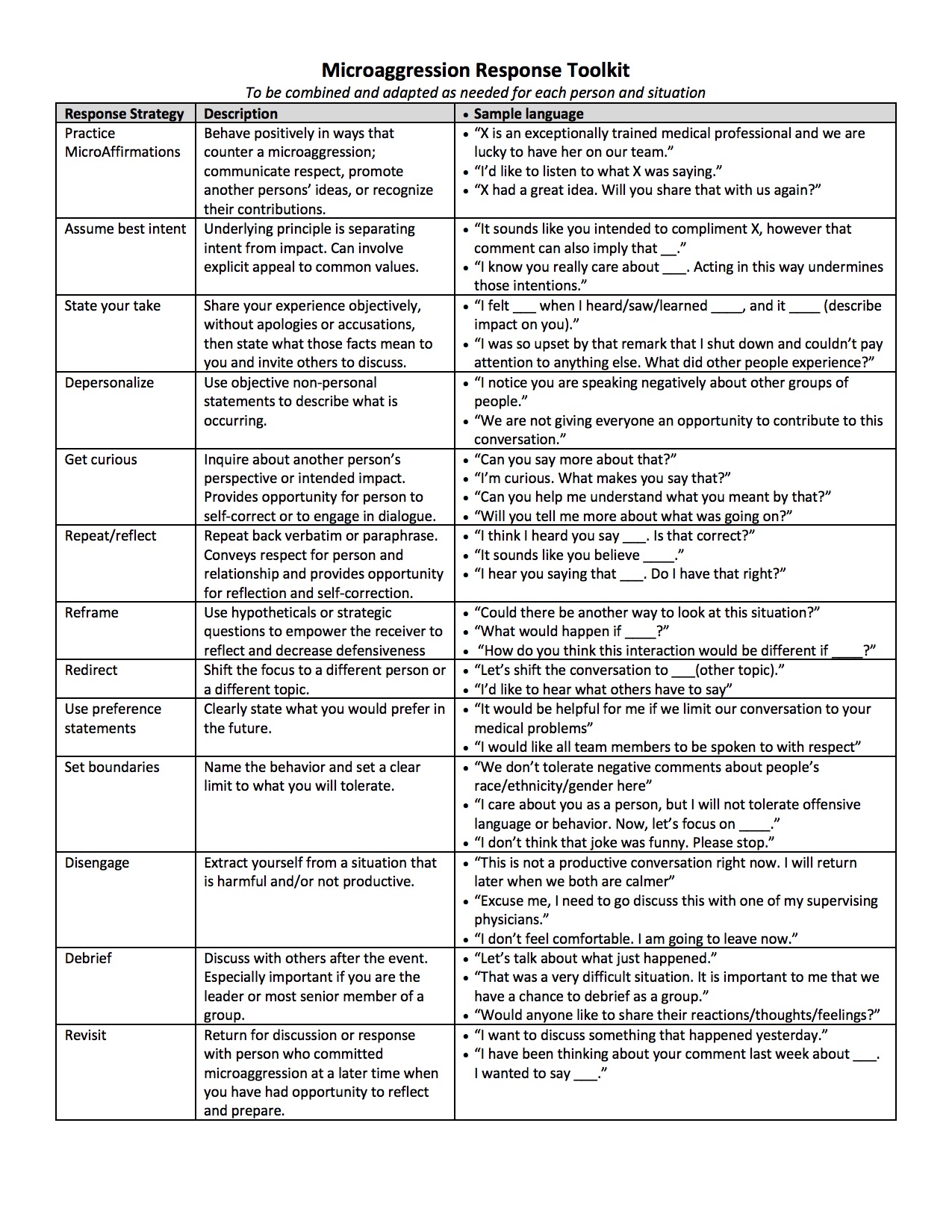

Description: We developed a Microaggression Response Toolkit based on a literature review and in consultation with a resident working group that describes various strategies individuals can adopt when they experience a microaggression as a target or as a witness (Figure 1). We designed a fifty-minute interactive workshop for internal medicine residents based on the Toolkit with the goals of: identifying microaggressions using case scenarios; describing the impact of microaggressions on provider wellbeing and the learning environment; and practicing various response strategies. Case scenarios used in the workshop were developed from examples in published works and from resident-reported microaggressions in our hospital. The workshop was led by a PGY3 resident (HF), and participants had access to the toolkit in print and electronically after the workshop. The workshop was delivered three times to approximately 85 residents (15 to 40 residents per session) of mixed post-graduate years (PGY1-PGY3) during April and May 2019, with brief and optional electronic pre- and post-surveys. Response rates varied between workshops, with a total of 55 responses to the pre-workshop (65% response rate, N = 85) and 37 responses to the post-workshop surveys (44% response rate). On the pre-survey, 75% of residents agreed or strongly agreed that training on microaggressions should be part of the residency curriculum (rated as 4 or 5 on a 1-5 Likert scale). In comparing pre- and post-survey responses, we found that residents reported increased comfort with identifying microaggressions (mean 4.1 post-survey vs 3.1 pre-survey), improved understanding of the impact of microaggressions (mean 4.3 post-survey vs 3.6 pre-survey), and increased confidence in responding to microaggressions (mean 3.7 post-survey vs 2.5 pre-survey). On the post-survey, 97% of residents agreed or strongly agreed that the workshop was a worthwhile use of their time (rated as 4 or 5 on a 1-5 Likert scale).

Conclusions: Participation in this brief, practical workshop using a Microaggression Response Toolkit was associated with improvements in residents’ self-reported comfort in identifying microaggressions, understanding of their impacts, and confidence in responding to them. Participants found the workshop valuable and wanted such training in the residency curriculum. Future work is needed to determine the durability of these benefits and whether reported comfort with addressing microaggressions translates into real-world experiences.