Background: Clinicians often diagnose bacterial infections such as urinary tract infection (UTI) and pneumonia in patients who are asymptomatic or have non-bacterial causes of their symptoms. Misdiagnosis of infection leads to unnecessary antibiotic use and potentially delays correct diagnoses. Interventions to improve diagnosis often focus on infections separately. However, if misdiagnosis is linked at the hospital level, broader interventions to improve diagnosis may be more effective. Thus, we assessed whether hospital rates of misdiagnosis of UTI and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) were correlated.

Methods: From 7/2017-7/2019, abstractors at 46 Michigan hospitals collected data on a sample of adult, non-intensive care, hospitalized patients with bacteriuria (positive urine culture) or who were treated for presumed CAP (discharge diagnosis plus antibiotics). Patients with concomitant bacterial infections were excluded. Using a previously described method,1,2 patients were assessed for UTI or CAP based on symptoms, signs, and laboratory/radiology findings. Misdiagnosis of UTI was defined as number of patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) treated with antibiotics /number of patients with bacteriuria. Misdiagnosis of CAP was defined as number of patients treated for presumed CAP who did not have CAP /number of patients treated for presumed CAP. Hospital-level correlation was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient between misdiagnosis of UTI and CAP. For patients with prescriber data (N=3,293), we also assessed ED-level correlation.

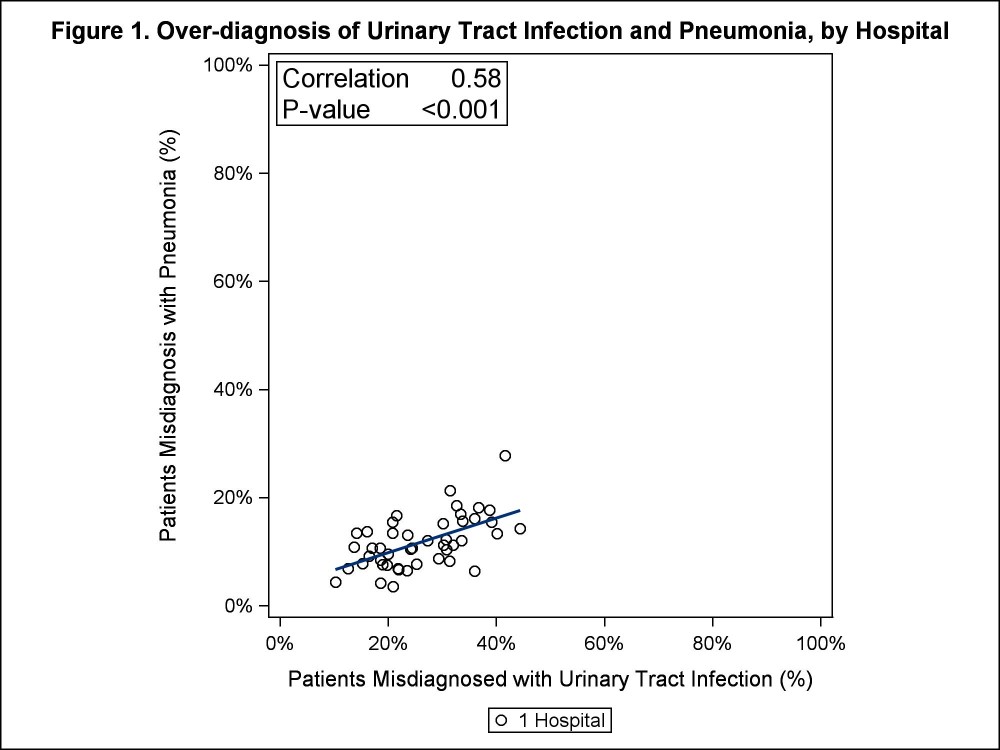

Results: Of 11,914 patients with bacteriuria, 31.9% (3796) had ASB. Of those, 78.3% (2973/3796) received antibiotics. Of 14,085 patients treated for CAP, 11.4% (1602) did not have CAP. Incidence of misdiagnosis varied by hospital—those with high rates of misdiagnosis of UTI were more likely to have high rates of misdiagnosis of CAP (Pearson’s correlation coefficient=0.58, P=<0.001; Figure 1).Of patients misdiagnosed with UTI, 54.2% (1159/2137) had antibiotic treatment started in the emergency department (ED); of those, 81.3% (942/1159) remained on antibiotics on day 3 of hospitalization. Of patients misdiagnosed with CAP, 75.3% (871/1156) had antibiotic therapy started in the ED with 90.6% (789/871) still on antibiotics day 3 of hospitalization. Hospitals with high rates of UTI misdiagnosis in the ED were more likely to have high rates of CAP misdiagnosis in the ED (Pearson’s correlation coefficient=0.33, P=<0.001).

Conclusions: Misdiagnosis of two unrelated infections was moderately correlated by hospital and weakly correlated by hospital ED. Potential causes include differences in organizational culture (e.g., low tolerance for diagnostic uncertainty, emergency department culture), organizational initiatives (e.g., sepsis, stewardship), or coordination between emergency and hospital medicine. Additionally, antibiotics initiated in the ED were typically continued following admission, potentially reflecting diagnosis momentum.