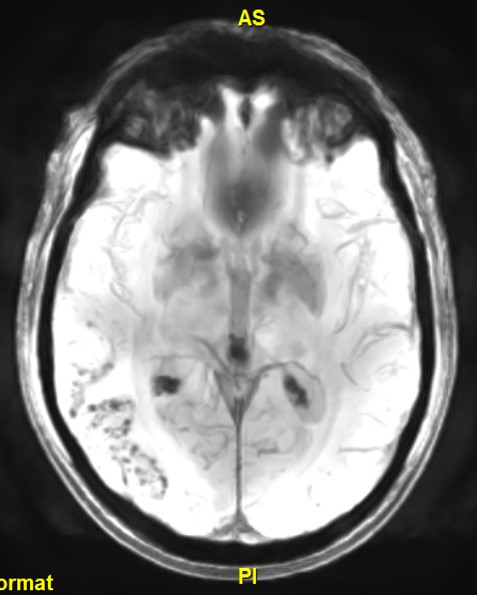

Case Presentation: A 57-year-old male comorbid with hypertension and benign prostatic hyperplasia presented to the emergency department with a 1-month history of worsening bifrontal headaches and progressive cognitive decline. The headaches were increasing in both frequency and severity, occurring throughout the day and night. He also endorsed nausea, light sensitivity, word-finding difficulty, and new memory impairments. Prior to this, he denied any history of headaches. His wife noted he was speaking more slowly with frequent pauses. Examination was significant for blood pressure of 195/130 and delayed speech initiation, but was otherwise normal, including high level cognitive functions. Serum chemistries, liver function tests, and complete blood count were within normal limits. CRP was mildly elevated at 5.5 (nl < 5) but erythrocyte sedimentation rate was normal. Lyme disease testing was negative. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed 2 total nucleated cells (54% lymphocytes), glucose 63 mg/dL, protein 38 mg/dL (normal < 35). Brain MRI with and without contrast demonstrated extensive T2 hyperintensity in the right temporal parieto-occipital region and underlying cerebral microhemorrhages on SWAN with vascular and leptomeningeal enhancement. Vessel wall imaging did not demonstrate evidence of angiitis. A diagnosis of CAA-ri was made by clinical manifestations and MRI findings. The patient was prescribed IV methylprednisone 1000 mg daily for three days and was to complete a 6-week oral prednisone taper, however, steroids were discontinued after 7 days of therapy due to significant steroid-induced mania. Antihypertensives were titrated to a systolic blood pressure goal of < 140 mm Hg. A follow-up MRI 2 months later demonstrated markedly improved T2 hyperintensity in the right temporal parieto-occipital region. His clinical outcome at follow-up was improved.

Discussion: CAA-ri is a rare and aggressive small-vessel disease characterized by an inflammatory response to deposits of amyloid protein in the cortical or leptomeningeal vessel walls. Clinical presentation includes acute or subacute onset progressive headaches, memory impairment, multidomain cognitive decline, behavioral changes, and seizures. Although gold standard for diagnosis is brain biopsy, this is often deferred given the invasive nature of this testing. The diagnosis is often made clinically based on symptoms and suggestive brain MRI findings, which classically reveal asymmetric, patchy white matter hyperintensities on T2-weighted sequences, leptomeningeal enhancement, and scattered microbleeds on gradient echo sequences. A set of clinical diagnostic criteria have also been proposed that have high sensitivity and specificity (82% and 97% respectively).1 The mainstay of treatment is an initial burst of high-dose steroids followed by a taper over 6-12 weeks with interval MRI brain and clinical examination to evaluate recovery. Imaging is completed 4-6 weeks post-treatment to monitor for treatment response. Relapses can occur and some patients are therefore transitioned to long term immunosuppressants. Although still rare in clinical practice, it is encountered with increasing frequency and will be particularly important to recognize as the novel amyloid targeting therapies can result in a similar inflammatory response.

Conclusions: Cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation (CAA-ri) is a rare clinical entity that is important to recognize as it has a favorable prognosis if diagnosed and treated early.