Case Presentation:

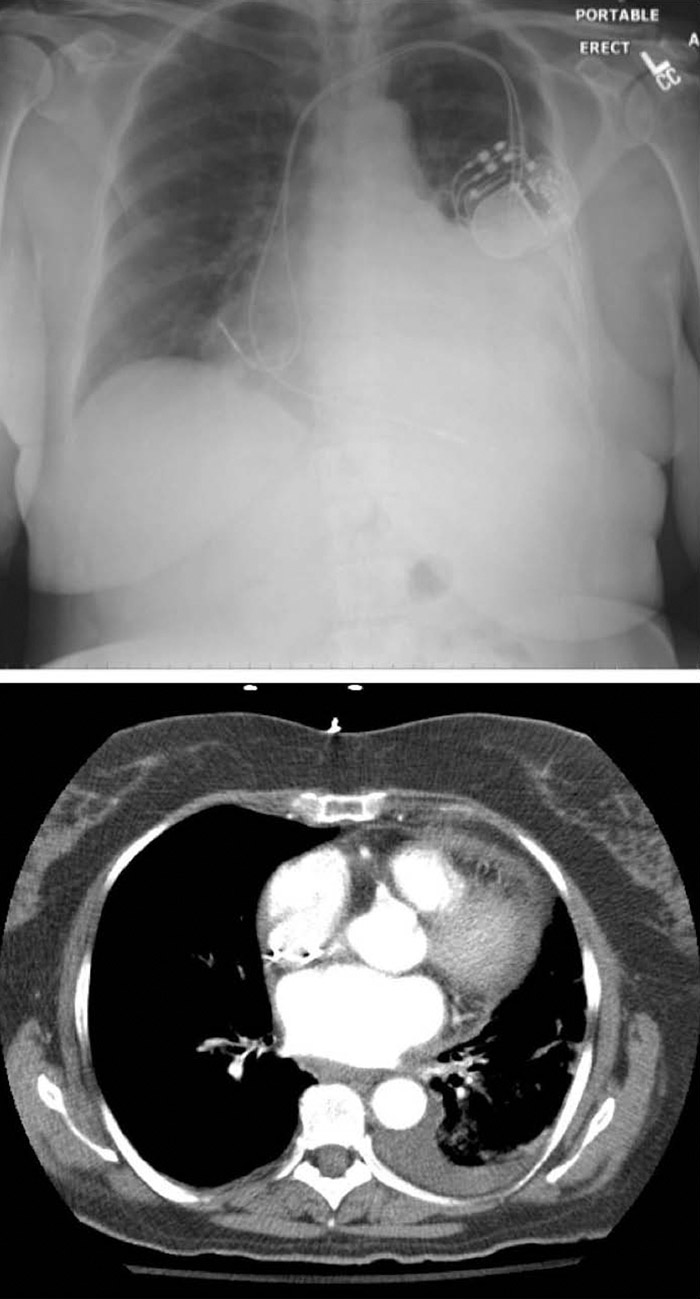

A 72‐year‐old woman with successful implantation of dual‐chamber permanent pacemaker presents two months after pacemaker placement with progressive shortness of breath. She was recently hospitalized one‐month prior for idiopathic pericarditis with hemorrhagic pericardial effusion, treated with colchicine and high‐dose aspirin. On current presentation, she was tachycardic to heart rate 120s, but vital signs were otherwise normal. Physical exam revealed irregular heart rhythm without rub, and decreased breath sounds on her left side. Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 26,800 cells/mm2 with a normal differential, lactate of 2.4, LDH 903. CXR and CT scan showed a large left sided pleural effusion and resolving pericardial effusion. Thoracentesis was performed with removal of 1.2L of dark‐amber fluid consistent with an exudative process. Analysis of pleural fluid revealed WBC 656 (lymphocyte 30%, macrophages 16%, mesothelial cells 29%, PMN 25%), glucose 97, protein 4.0, LDH 157. The fluid was negative for cytology, AFB, bacteria, and fungi. Given an initial suspicion of a parapneumonic pleural effusion, she was started on antibiotics for possible community‐acquired pneumonia, however, these were discontinued after infection had been excluded. As she was recently started on amiodarone for refractory atrial fibrillation, studies for drug‐induced lupus were sent. She was placed on prednisone 60 mg daily for possible drug‐induced lupus with immediate benefit. Complement levels and anti‐histone antibodies were negative, leading to a clinical diagnosis of post‐pericardiotomy syndrome. She was discharged with marked symptom relief on a prednisone taper.

Discussion:

Post‐pericardiotomy syndrome (PPS) is a relatively common complication following cardiac surgery, occurring in 10‐40% of patients, days to several weeks after a surgical procedure. Placement of pacemaker electrode leads can lead to damage of the pericardial cells, and blood in the pericardial space is believed to release cardiac antigens which stimulate an inflammatory response in the pericardium, pleura and lung, despite the absence of a perforation. Criteria for diagnosis of PPS is based on the presence of at least 2 criteria: fever without evidence of systemic or local infection, pleuritic chest pain, friction rub, evidence of pleural effusion, evidence of new or worsening pericardial effusion.

Conclusions:

Though the prevalence of postpericardiotomy syndrome following cardiac surgery is known, there have only been few case reports describing PPS following permanent pacemaker implantation. The nonspecific and mild symptoms and low index of suspicion may be reasons that cases are unrecognized. Awareness of the potential for pericardial complications following pacemaker implantation, even in the absence of perforation, may prevent prolonged hospitalization, serious complications like tamponade and constrictive pericarditis. Early treatment with anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS, colchicine), and/or prednisone have been shown to be effective in reducing morbidity and mortality, and avoid further surgical intervention