Case Presentation:

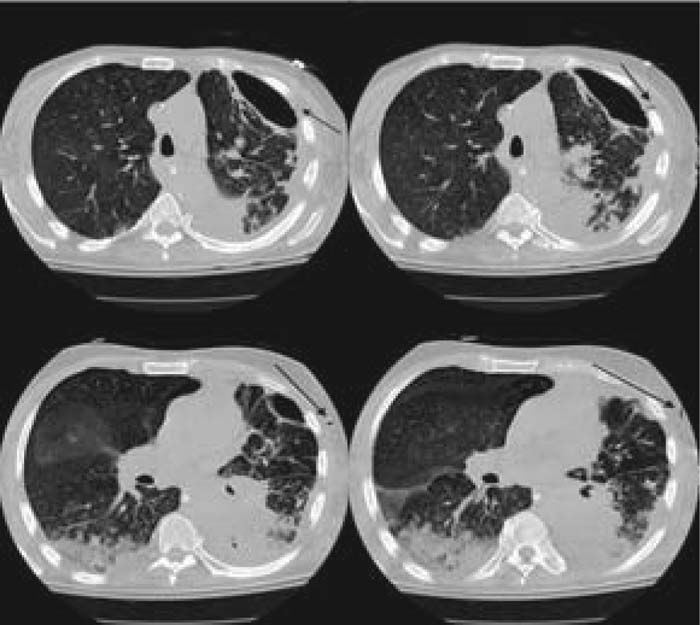

An 88‐year‐old man presented to the emergency room with respiratory distress, severe leukocytosis, and a large loculated effusion with an air‐fluid level in the left hemithorax. He was intubated and started on broad‐spectrum antibiotics. A pigtail catheter was inserted, yielding purulent material. Fluid cultures were positive for Prevotella oralis. Drainage decreased, and the catheter was removed. CT scan of the chest demonstrated a loculated anterior pneumothorax in the space formerly filled with empyema and a communication between the pleural space and the skin. The pathway of this pleurocutaneous fistula approximated that of the initial chest tube. A second chest tube was placed and removed after drainage of the pneumothorax, with no evidence of an ongoing air leak. Repeated imaging revealed recurrence of the loculated pneumothorax and persistence of the fistula. Examination of the chest wall identified cyclical escape of air through the chest wall via the fistulous tract. The patient's clinical status deteriorated, and comfort care measures were instituted per family wishes.

Figure 1. CT of the chest demonstrating a communication between the pleural space and the skin, representing a pleurocutaneous fistula.

Discussion:

A series of events can explain the formation of the fistula. First, Prevotella oralis pneumonia developed, presumably from aspiration of the organism and an impaired defense system. Then there was rupture into the pleural space, causing a hydropneumothorax, which became infected and loculated. There was persistence of a bronchopleural fistula, leaving a loculated pneumothorax. Finally, there was formation of a tract through the chest wall with air escape, cyclically replenished via a ball‐valve‐type bronchopleural fistula (the entire system functioning akin to a bellows). The air flow maintained patency of the fistula. Prevotella oralis colonizes the mouth but rarely causes extraoral infection. The term pleurocutaneous fistula in the literature most commonly refers to a communication between the pleura and the subcutaneous tissues, not a tract that extends from the pleura to outside air. Apart from surgical (intentional) etiologies, we were able to find only 4 reports of relevant cases due to other causes: chronic empyema, thoracoscopy, and radiation for breast cancer.

Conclusions:

True pleurocutaneous fistula is exceedingly rare. Ours is a case in which empyema, loculated pneumothorax, and a ball‐valve mechanism in a compromised host appear to have combined to create this phenomenon

Author Disclosure:

H. Ghanem, none.