Background: Pediatric venous thromboembolism (VTE), although less common than in adults, is increasingly recognized as a significant and preventable cause of morbidity and mortality. There are no universal pediatric VTE guidelines, although the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) limits prophylaxis recommendations to a limited set of risk factors. Multiple centers have published institutional guidelines based on available data and expert opinion. Our objectives were: (1) to determine risk factors for hospital acquired VTE (HA-VTE) in pediatric patients from 2008 to 2017 at Baystate Children’s Hospital (2) to determine whether ACCP guideline or Cincinnati Children’s published guideline would have recommended VTE prophylaxis in these patients

Methods: A retrospective chart review was conducted seeking to identify HA-VTE in hospitalized pediatric patients at our institution, an urban, tertiary-care children’s hospital. Inclusion criteria were patients ≤21 years of age from 2008 to 2017 with VTE, as identified using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes. HA-VTE was defined as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) including clots in deep veins in the upper and lower extremities, cerebral sinuses, right atrium, abdominal veins and pulmonary embolism (PE) after 48 hours of admission. Subsequently, we applied (1) the ACCP guidelines for VTEP and (2) Cincinnati Children’s Medical Center (CCMC) guidelines for VTE prophylaxis to determine which of these cases would have been treated with VTE prophylaxis based on these guidelines.

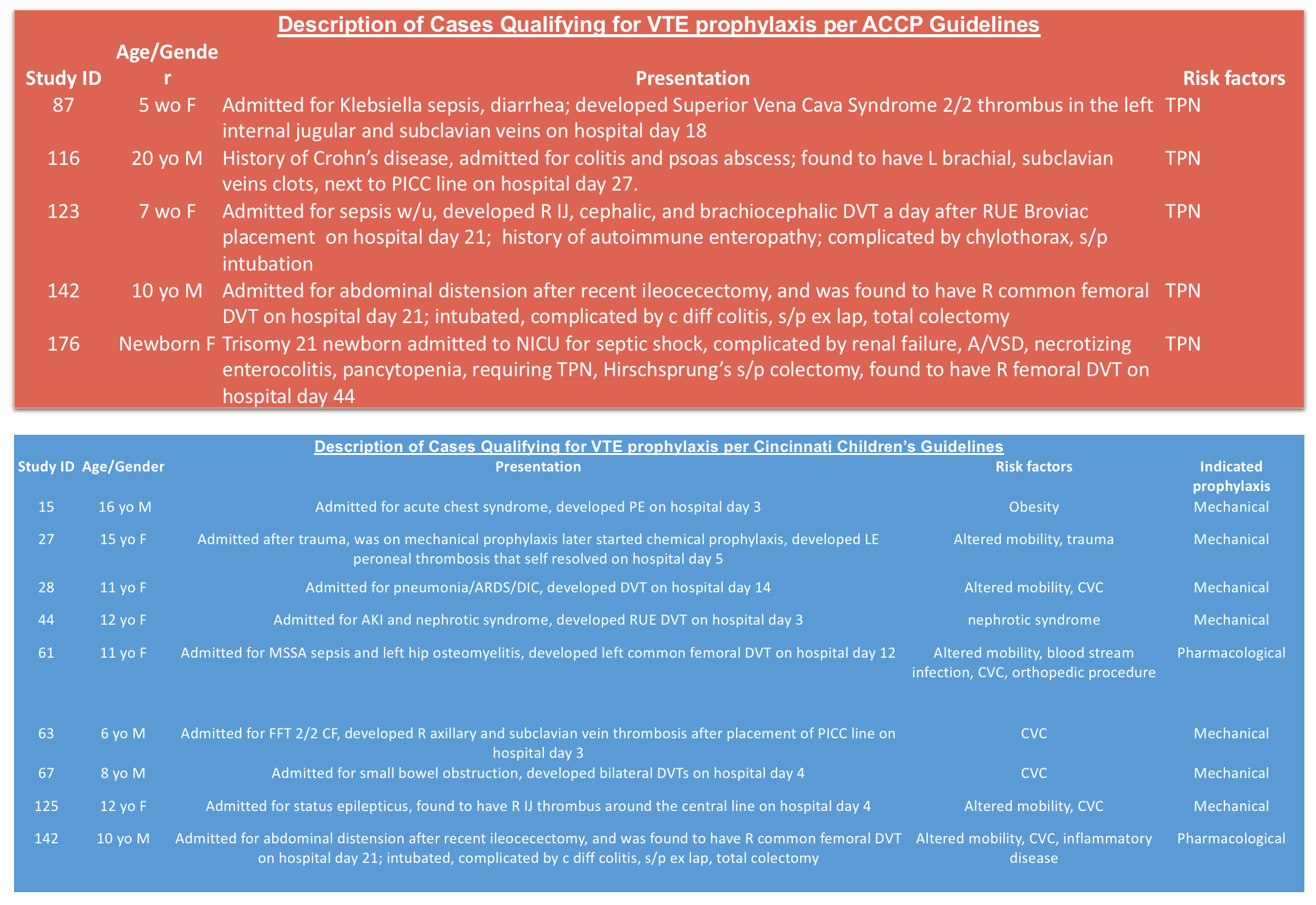

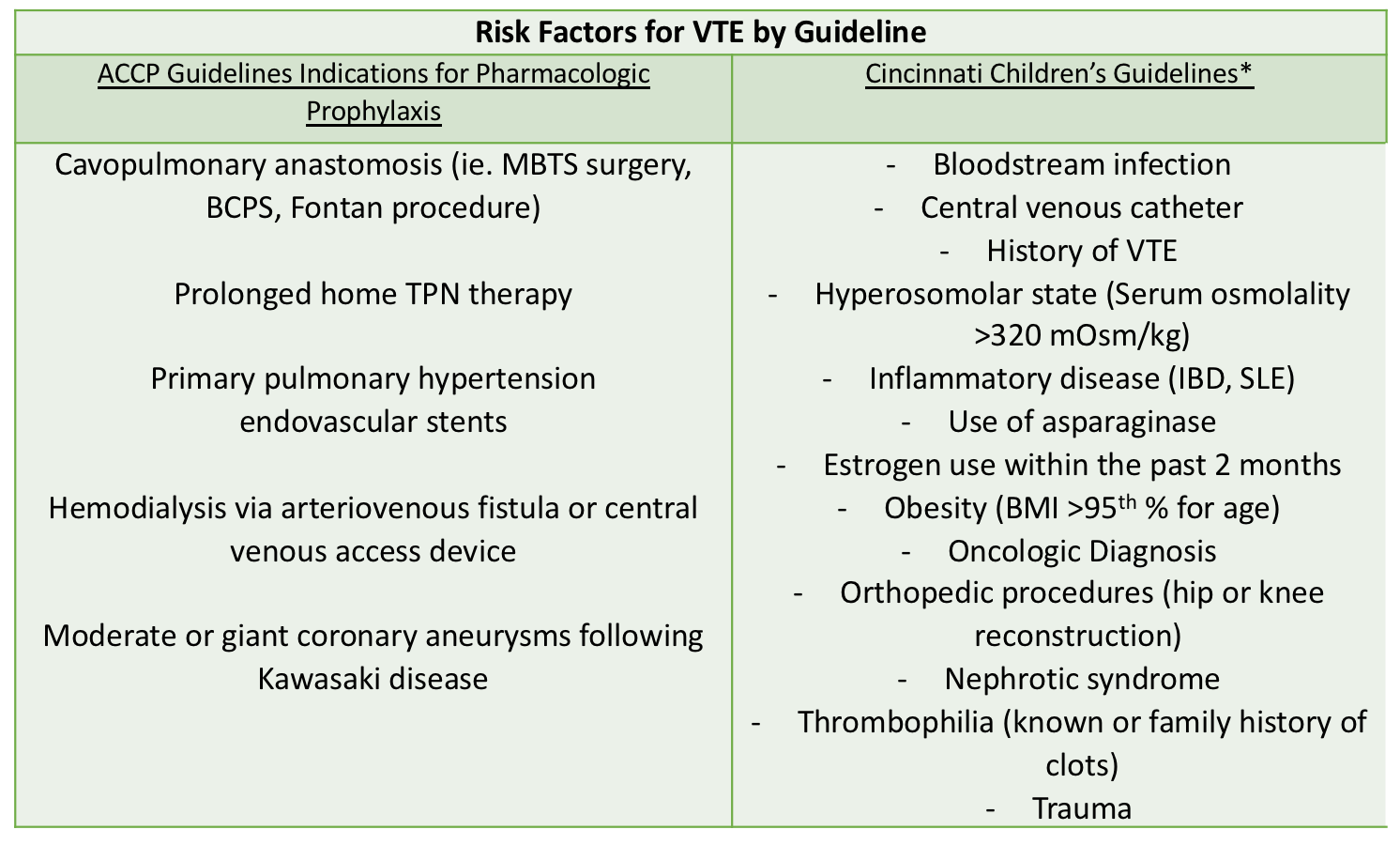

Results: Out of 98477 hospital admissions, 178 VTE cases were identified (18 cases per 10,000 admissions). 19% of the VTE cases are hospital-acquired and 41% of the HA-VTE patients were under 1 year of age. The most common risk factor for HA-VTE (82%) was the presence of a central venous catheter (CVC). 16% (5/34) of the HA-VTE cases would qualify for ACCP guideline prophylaxis, with all 5 cases are associated with prolonged total parenteral nutrition (TPN) requirement. 27% (9/34) of the HA-VTE cases would qualify for Cincinnati’s guideline prophylaxis, with all 9 cases are associated with the presence of a CVC. All of the cases that did not qualify for Cincinnati’s prophylaxis were due to patient’s age being outside of the guideline rangeAll patients that are ≥ 18 years qualify for prophylaxis per our institution’s adult VTEP guidelines.

Conclusions: HA-VTE carries increased morbidity and mortality for hospitalized adults and children. Although recognition and prevention of HA-VTE in adult populations are routine, prophylaxis for pediatric HA-VTE is not commonly practiced. This may be due to the rarity of the disease and the challenge of identifying risk factors for HA-VTE. Our results suggest that published guidelines recommend prophylaxis in only a minority of pediatric patients who would have subsequently developed HA-VTE at our institution. Further modification and validation of current guidelines are needed to effectively prevent pediatric HA-VTE.