Background: Hypoglycemia occurs frequently in hospitalized adults with diabetes, and is associated with adverse clinical events, increased use of rapid response teams, prolonged hospital length of stay, and higher healthcare costs (1). Identifying risk of hypoglycemia in hospitalized adults is vital to preventing adverse events and maximizing patient safety. However, there are no tools/models to predict risk of hypoglycemia. To address this major clinical gap, we sought to develop a machine learning model to predict hypoglycemia in hospitalized adults with diabetes.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective analysis across a tertiary healthcare center’s 19 hospitals across the United States, from July 2017 to March 2024. The cohort included 179,495 adults (age ≥18 years) with diabetes admitted to medical and surgical services, of which, 121,262 had blood glucose readings. Hypoglycemia was defined as having ≥1 blood glucose ≤70 mg/dL (2). We extracted 33 individual-level features from the electronic health record, encompassing demographics, comorbidities, medications, laboratory data, and clinical characteristics. Rurality was determined using Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes for patient residence, and laboratory data temporal trends (i.e., slopes) were calculated using linear mixed-effect models. An XGBoost model was developed with an 80/20 train-test split, employing SMOTE (3) oversampling to address class imbalance (75% without and 25% with hypoglycemia). Model interpretability was assessed using SHAP scores (4) to identify key predictive features, with higher SHAP scores indicating a greater contribution to the model’s predictive power. Analyses were conducted using Python programming Language within our institution’s Google Cloud Platform (5).

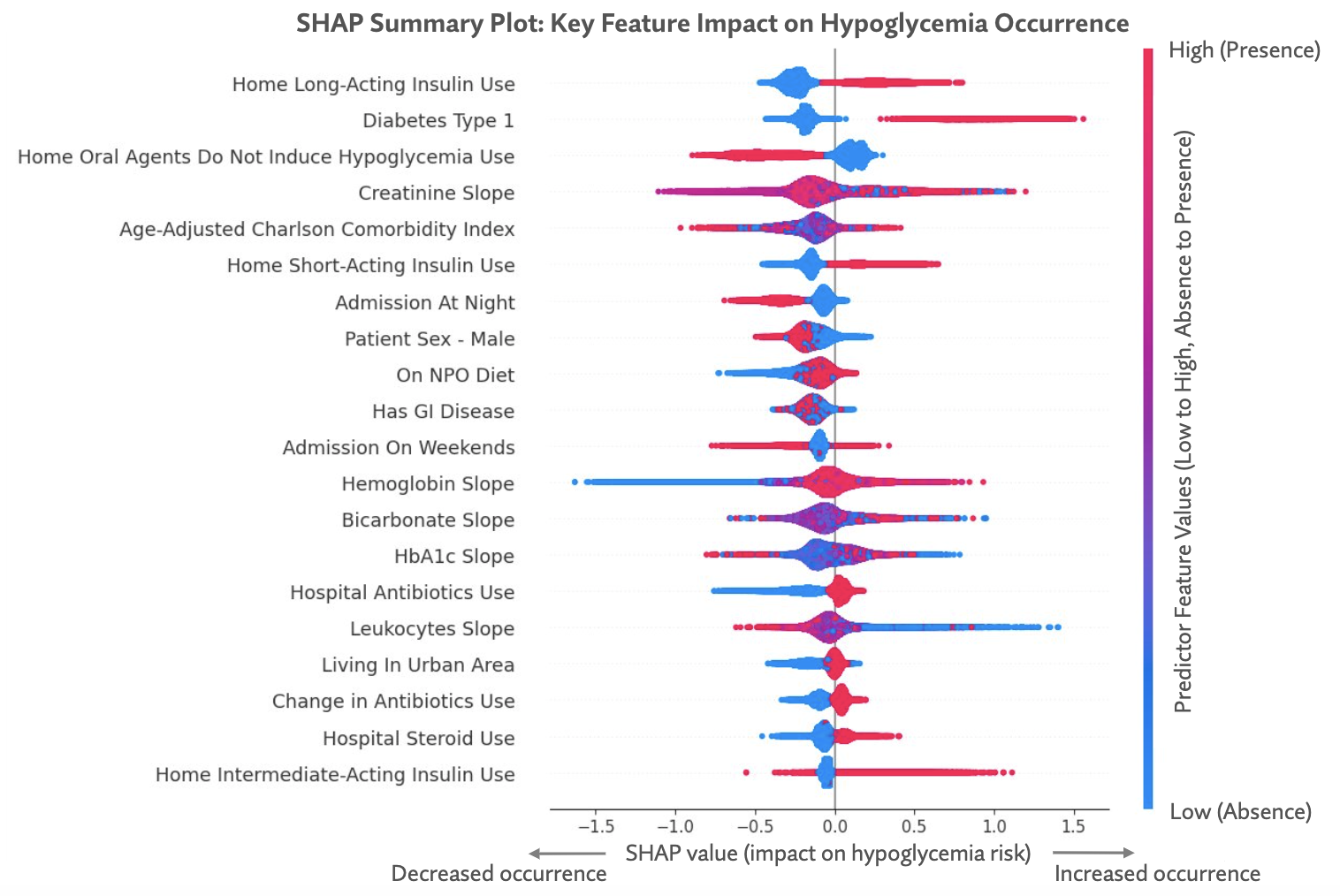

Results: The cohort of 121,262 admissions had a mean (SD) age of 64.3 (14.6) years and included 56.9% men (n = 69,050), 87.9% adults of white race (n = 106,666), and 63.3% adults of urban residence (n = 76,732). Among the admissions, 13.8% had ≥1 episode of hypoglycemia, 12.6% had type 1 hypoglycemia (glucose 54–70 mg/dL) and 4.8% had type 2 hypoglycemia (glucose < 54 mg/dL). The model had high accuracy (0.86), specificity (0.88), and sensitivity (0.97) to predict absence of hypoglycemia during hospitalization (Table). Key model predictors of higher hypoglycemia risk were use of long- or short-acting insulin at home (SHAP score: 0.25), type 1 diabetes (SHAP score: 0.25), and receiving steroids (SHAP score: 0.07) or antibiotics (SHAP score: 0.06) in the hospital. In contrast, key predictors of lower risk of hypoglycemia were taking oral non-hypoglycemic diabetes medications at home (SHAP score: 0.23), being admitted to the hospital at night (SHAP score: 0.16), and being of male sex (SHAP score: 0.14). (Figure)

Conclusions: In this large multisite analysis of adults hospitalized with diabetes, hypoglycemia type 1 and type 2 occurred frequently. A model to predict hypoglycemia included modifiable factors associated with higher and lower risk of hypoglycemia. The model had high sensitivity and may guide strategies to match hypoglycemia risk with frequency of glucose testing. Tailored management in the hospital may reduce the burden on nurses and hospitalists and improve patient experience. To our knowledge, this is the largest study of hypoglycemia in the hospital, and further studies are required to evaluate the model in relation to clinical outcomes and to validate it in other healthcare centers.