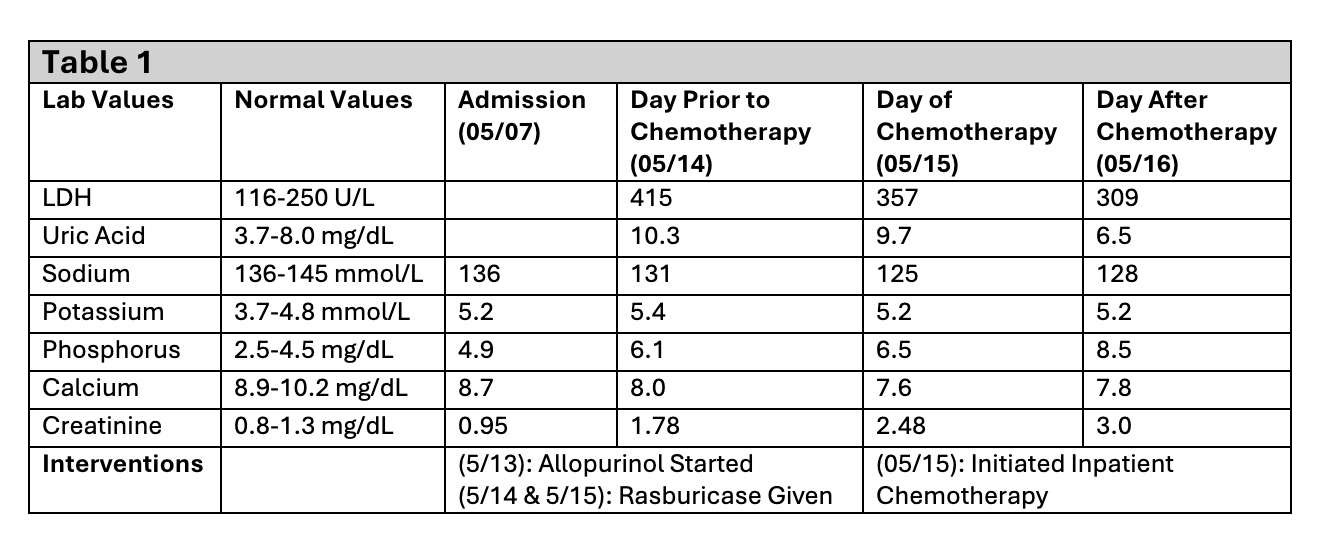

Case Presentation: A 39-year-old male presented with persistent abdominal pain and was found to have a large, left-sided renal mass measuring 15 x 11 x 23 cm. Initial biopsy results were inconclusive, demonstrating nonspecific necrosis and inflammation. Two weeks later the patient developed worsening abdominal distention and acute kidney injury. He was found to have lung and liver nodules concerning for metastases on computer tomography (CT) imaging. Imaging also demonstrated significant rapid interval development of numerous soft tissue nodules ranging from 12 to 22 mm in size consistent with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Repeat biopsy was consistent with sarcoma. During work up for his renal mass the patient was noted to have increasing creatinine levels as well as hyperphosphatemia, hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia, hyperuricemia and elevated lactate dehydrogenase. Given that the lab values and findings were consistent with tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) and rapid mass enlargement with peritoneal spread, chemotherapy was initiated urgently with doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and mesna. He was further treated with allopurinol and rasburicase. Notable labs and interventions noted in Table 1. The patient was diagnosed with rapidly progressing retroperitoneal sarcoma and developed spontaneous tumor lysis syndrome prior to chemotherapy. Multiple services were involved in the patient’s care throughout their admission.

Discussion: TLS is an oncological emergency caused by massive lysis of malignant cells and release of intracellular components into the blood stream which can result in multiple electrolyte abnormalities as well as secondary complications including cardiac arrhythmia, seizures, and death. Due to the life-threatening complications TLS requires immediate recognition and management. TLS typically occurs in hematological malignancies and less commonly in cases of solid tumors. In cases with solid tumors, TLS is frequently observed after initiation of anti-cancer therapies. In rare cases, spontaneous TLS occurs in patients with solid tumors without exposure to anti-cancer therapies. The incidence of spontaneous TLS in solid tumors is unknown but in prior reviews of TLS in patients with solid tumors 24% of cases occurred spontaneously. Spontaneous TLS in sarcoma is an extremely rare event with only cases reported in the literature.This case highlights the critical role of the hospitalist as the central coordinator of care for complex patients requiring multidisciplinary management. Hospitalists frequently care for hospitalized patients with cancer, whether due to initial diagnosis, complications of anti-cancer therapies, or due to an acute illness. Managing a patient with advanced cancer demands heightened vigilance for the malignancy’s progression and associated complications. These patients often have intricate medical and psychosocial needs, necessitating seamless coordination among oncologists, consulting specialists, nursing staff, and social workers. The hospitalist’s ability to integrate and synchronize these efforts is crucial in delivering comprehensive, patient-centered care.

Conclusions: This case emphasizes the importance of rapid recognition of TLS as a potential complication of a possible malignancy and the necessity of an urgent oncological consult in setting of rapidly enlarging mass, even without conclusive tissue biopsy. It highlights how hospitalists are essential in recognition of complications, coordinating care and timely interventions.