Case Presentation: A 60-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus presented to the emergency department with a progressive lower extremity rash, abdominal discomfort, and diarrhea. The patient was hospitalized five days prior for lower extremity cellulitis and was discharged on clindamycin. After discharge, he developed a bilateral lower extremity rash, which migrated to his back and face.Laboratory investigations revealed elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), along with elevated complement component three (C3). Liver function tests demonstrated elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), with a negative hepatitis panel. Skin biopsy was performed with a histopathology report of folliculitis and a small focus of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV). Immunological assays indicated positive antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody, and antimitochondrial antibody, with negative results for anti-SCL 70, anti-Smith, anti-SSA, anti-SSB, anti-histone, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA).The patient was initiated on methylprednisolone 40 mg inpatient and discharged with a rheumatology outpatient follow-up. A repeat immunological panel was negative for ANA, anti-dsDNA, and antimitochondrial antibody, further supporting the diagnosis of clindamycin-induced LCV.

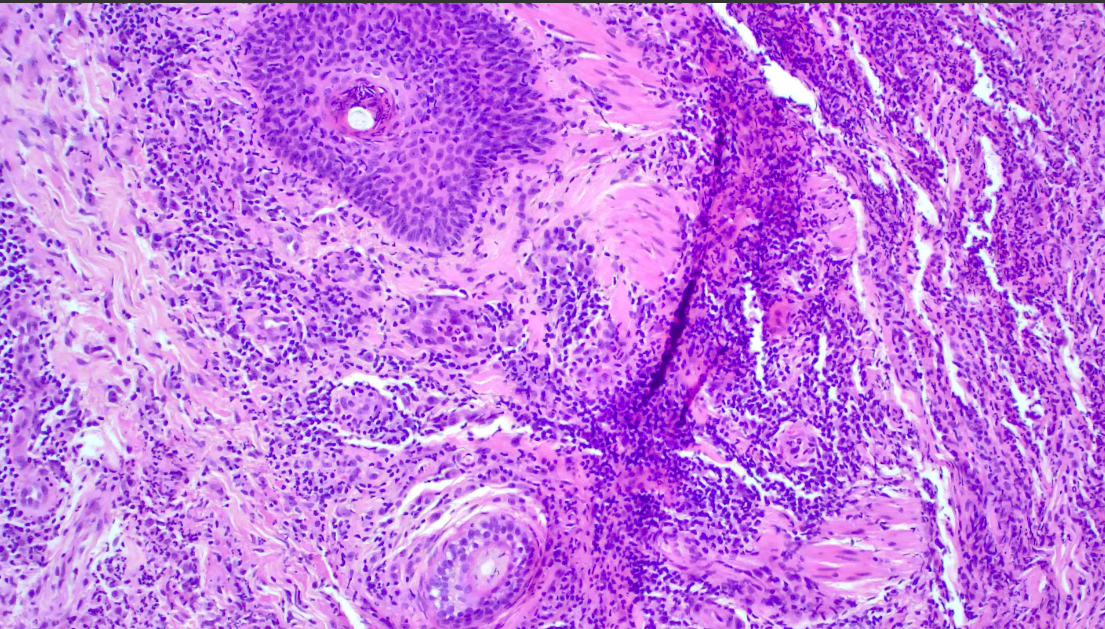

Discussion: LCV is an immune complex-mediated vasculitis of the dermal arterioles, capillaries, and venules in which neutrophils infiltrate vessel walls and surrounding structures. Annually, the incidence of biopsy-confirmed LCV is about 45 per million people. About 10% of vasculitis are drug-induced and cutaneous manifestation onset occurs 1-3 weeks after drug initiation. Antibiotics are one of the biggest culprits of secondary LCV, with beta-lactams being the most common. Recently, researchers have reported the induction of LCV from Oxacillin, ceftriaxone, and cefazolin use. Clindamycin-induced LCV is uncommon as there appears to be a singular reported case of clindamycin-induced leukocytoclastic angiitis within the last 50 years. As clindamycin is frequently used in an inpatient setting to cover for MRSA infections, awareness of LCV in the setting of clindamycin is valuable for guiding patient care.The severity and progression of LCV are often assessed using cutaneous biopsy findings. In early stages, the histopathological presentation of LCV may include focal damage of capillary vessel walls as well as mild granulocytic infiltrates. As part of the work-up for patients with suspected LCV, a cutaneous biopsy should always be performed as it will give insight into disease prognosis and systemic complication risk.

Conclusions: The patient in this report exhibited cutaneous changes of bilateral legs, abdomen, and face. The localization of LCV in this patient is uncommon, and so it elucidates the possibility of under diagnosis of LCV if it presents outside the typical anatomical predilection.There is limited access to dermatologists in rural areas, specifically within the inpatient setting. Tele dermatology should be expanded and implemented in rural hospital systems as it would assist in timely diagnosis of cutaneous disorders and foster interdisciplinary collaboration.