Background: Patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) often face frequent emergency department (ED) visits and hospital readmissions, primarily driven by challenges in pain management, stigma, and system-level barriers. Existing interventions at the CU Division of Hospital Medicine, such as cohorting patients with specific teams, multidisciplinary care conferences, and implementing care plans for high-utilizer patients, have provided some relief but lacked direct patient engagement in their design. Integrating patient perspectives is essential for fostering trust, addressing personhood, and creating care strategies that are both effective and compassionate.

Purpose: The aim of this project was to employ a design-thinking approach to integrate patient perspectives into the creation of individualized care plans for patients with SCD. By leveraging this innovative, human-centered framework, the project sought to develop tools and processes that would promote collaboration between patients and providers, improve trust, and address systemic barriers to quality care.

Description: Design thinking, a structured, iterative process, was used to ensure that patient needs and experiences informed every stage of development. This process consists of five phases: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test. During the empathize phase, we conducted five in-depth interviews with hospitalized patients experiencing SCD pain crises. Empathy and journey maps were created from these interviews, leading to the development of a representative patient avatar. This avatar reflected key themes in patient experiences: trust vs. distrust, control, stigma, perceptions of pain, burden, connection, and dismissal.In the define phase, central challenges were identified using “why-how laddering” and “how might we” statements, which revealed core issues related to establishing trust and recognizing the patient as a whole person. During the ideate phase, potential solutions were brainstormed and analyzed through affinity mapping, which prioritized interventions based on feasibility and impact. Prototypes were then developed, including personalized care plans for outpatient and inpatient settings and an interactive communication tool to enhance dialogue between patients and providers. Testing with two hospitalized patients provided initial feedback, which guided further refinement of the prototypes.

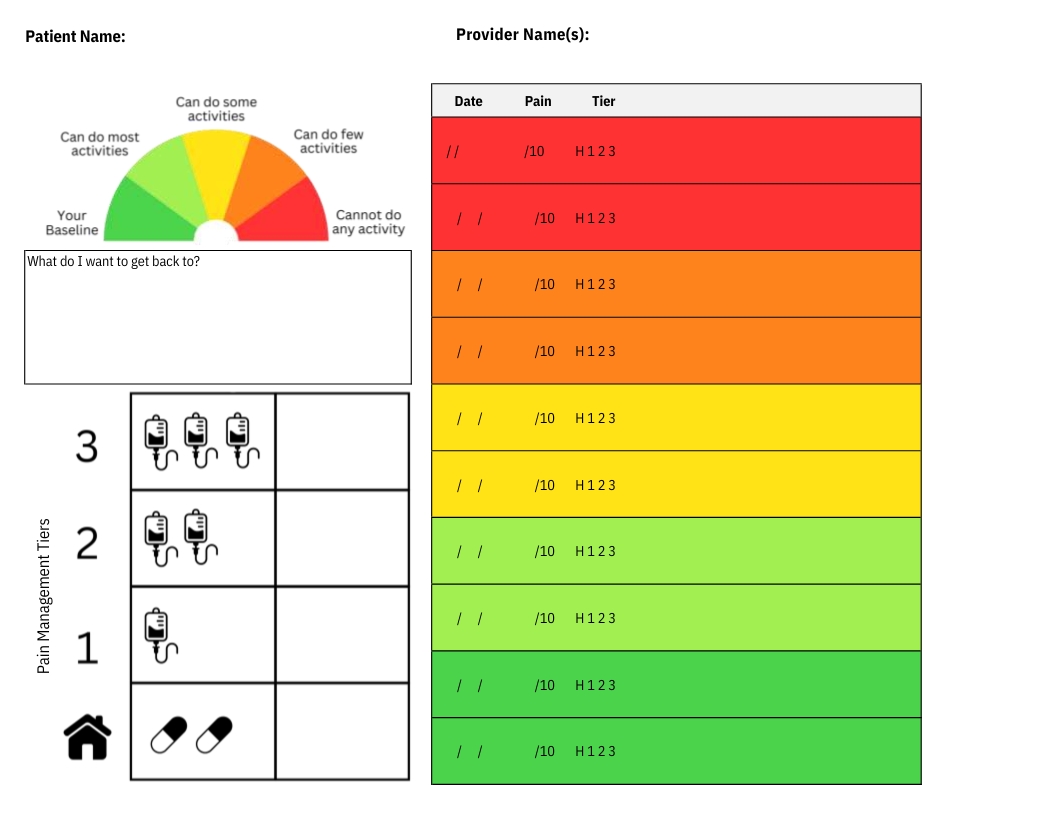

Conclusions: The final product includes a daily collaboration tool designed to improve patient-provider communication. This tool features a pain log, an activity ability meter with goal-setting options, and a visual pain management tier system outlining dosages and frequencies of interventions. These components are consolidated into a physical care binder, which also includes detailed care plans for home, ED, and inpatient use. While the limited number of patients involved in testing represents a constraint, the project highlights the transformative potential of design thinking in healthcare. By systematically incorporating patient experiences into the development process, healthcare providers can create tools and strategies that enhance trust, improve outcomes, and provide more compassionate care. Future iterations of this project will expand testing to include a broader patient and provider population to ensure scalability and long-term effectiveness.