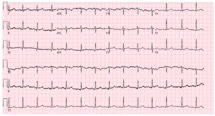

Case Presentation: A 48-year-old female with an unremarkable past medical history presented with intermittent, dull, substernal chest pain for several hours, associated with diaphoresis and bilateral arm paresthesia, worse with exertion. Patient’s symptoms improved with sublingual nitroglycerin in the Emergency Department. EKG showed subtle ST-segment elevations inferiorly. Troponin was initially negative at 0.01, trended to 0.02 and 0.06, and she was admitted to hospital for further management of possible acute myocardial infarction (MI). Repeat EKG showed no acute changes. Patient’s cardiac enzymes continued to rise, and she was started on a standard protocol including heparin drip. Patient underwent cardiac catheterization which was positive for spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), with significantly tortuous vessels at the terminal portion of the LAD. Due to the size of the distal vessel, patient was managed with appropriate medical therapy. Patient clinically improved and was discharged with outpatient cardiology follow-up within a week for further outpatient management and monitoring.

Discussion: Chest pain is one of the most common chief complaint seen in the emergency department. Although acute coronary syndrome (ACS) secondary to thrombus occlusion should always be considered initially, a broad differential to include other non-thrombotic causes of chest pain such as SCAD is vital, especially in patient with limited risk factors, to assure prompt diagnosis and appropriate early intervention. SCAD often present with ST-segment elevations, elevated cardiac biomarkers, and angina, especially in women, especially post-partum or with collagen disorder. Our patient presented with classical symptoms for ACS. However, she had no risk factors for ACS and very low cardiac risk (such as TIMI) score on calculations. Many times, chest pain with negative cardiac enzymes is often associated with muscular or gastrointestinal dysfunction. As an internist, it is important to be cognizant of how SCAD can present and how it is treated. In the acute setting of SCAD, management is dictated by the location and severity of the distal vessels and the hemodynamic stability of the patient. Invasive therapies such as CABG and PCI have been tried for patients with SCAD, but neither is the treatment of choice. Since revascularization in patients with SCAD is challenging and associated with higher risks of complications, a conservative approach is recommended especially in patients with non-critical angiography imaging, normal TIMI scores, and hemodynamic stability. It is recommended by experts that patients should take aspirin daily. Other medications such as beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and nitrates are used more for patients with comorbidities. Statins are advised for primary prevention. Follow-up post-discharge is also vital as SCAD is known to reoccur over time.

Conclusions: After acute coronary syndrome is ruled out, chest pain is often attributed to muscular or gastrointestinal symptoms. However, an internist should be aware of other cardiac causes of chest pain especially given the risk factors of SCAD.