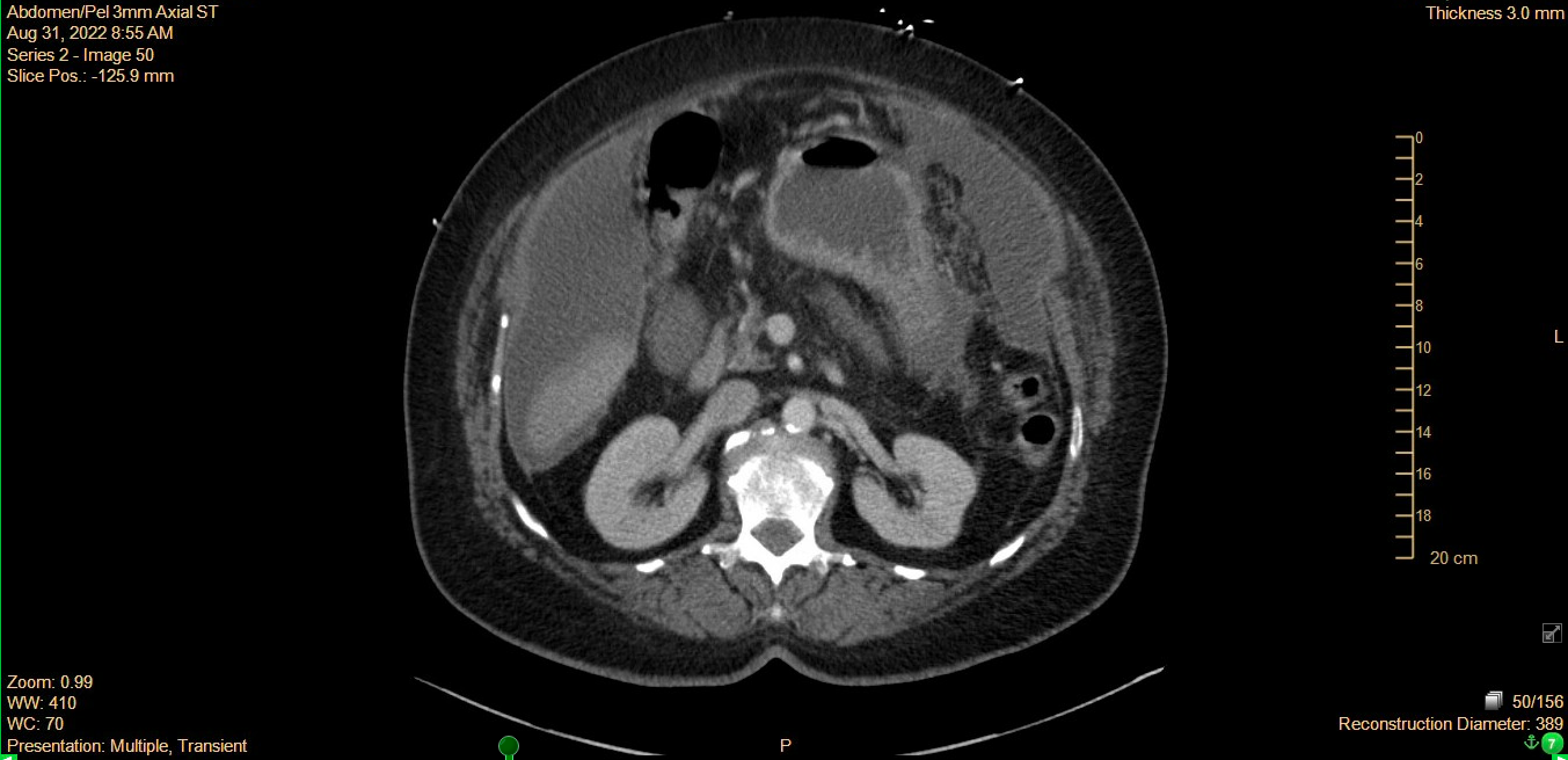

Case Presentation: We present the case of a 67-year-old female with a history of GERD, diabetes, and remote breast cancer treated with lumpectomy, radiation, and tamoxifen who presented with one-month of persistent abdominal distension associated with anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and shortness of breath. In addition, she had one episode of severe epigastric pain that radiated throughout her chest and into her jaw prompting her to call 911. She denied changes in weight, fevers, chills, cough, constipation, or lower extremity swelling. Her breast cancer had been in complete remission for eight years and she was up-to-date her annual mammogram and screening colonoscopies. She was a non-smoker and had no significant alcohol intake. Family history was notable for stomach cancer in her paternal grandfather and grandmother and thyroid cancer in her twin sister. At the time of admission, she was afebrile and her vital signs were stable. Initial workup was remarkable for a microcytic anemia, mild hyponatremia, hypoalbuminemia, and negative troponin. Her electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with occasional premature atrial beats. A CT scan of her abdomen and pelvis revealed moderate volume ascites and haziness and nodularity of omentum concerning for peritoneal carcinomatosis (Figure 1). She had a diagnostic paracentesis with 4 liters of clear, yellow-green fluid removed. Ascitic fluid studies were remarkable for malignant cells differentiated as adenocarcinoma of primary peritoneal or gynecologic origin. CA 19-9 and CA-125 tumor markers were elevated. No ovarian or uterine masses were detected on pelvic ultrasound. The patient was established with a gynecologic oncologist and started on neoadjuvant therapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin.

Discussion: The sensitivity of ascitic fluid cytology in detecting cancer in the peritoneum ranges from 67% to 95% percent.[1,2,3] Even when a paracentesis yields malignant cells, it can be difficult to ascertain the primary tumor in ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal cancers due to their common origin in the embryonic Mullerian system.[4] Oncologists often consider these diagnoses collectively given this overlap.[5] Among these cancer types, primary peritoneal cancer is the rarest with the annual incidence estimated to be 6.78 cases per million.[6]This patient’s cancer was treated with a neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen typically used for advanced stage ovarian cancers. Increasingly, chemotherapy prior to surgical debulking has been used and shown to be non-inferior to adjuvant chemotherapy following surgery in terms of mortality.[5]

Conclusions: Primary peritoneal cancer is a rare disease that can be clinically and histologically indistinguishable from ovarian or fallopian tube cancers. Hospitalists are often the first physicians to evaluate a patient with a new diagnosis of cancer and may be the first to perform a paracentesis on patients with malignant ascites. In these cases, a bedside ultrasound-assisted paracentesis may be sufficient for the diagnosis and should be considered when availability of laparoscopic or imaging-guided biopsy is limited. Importantly, proceduralists should consider the small but potential risk of tumor seeding into the abdominal wall and minimize incision site exposure to needle contents.[7]