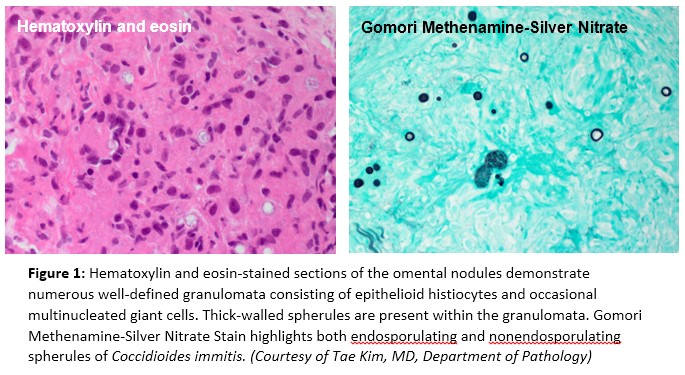

Case Presentation: A previously healthy 50-year-old man presented with 4 days of abdominal distension and subjective fevers at home. He was from rural Guatemala originally, now moved to Irvine, California. He denied any noxious habits including alcohol consumption, other travel history, or occupational exposures. On presentation, vital signs were stable except for slight tachycardia to 110s, and low grade fever to 37.9 C. Physical exam was notable for a distended abdomen with fluid wave, but was otherwise unremarkable. Paracentesis showed ascitic fluid with a low serum-ascites albumin gradient (0.7 g/dL), and somewhat elevated adenosine deaminase (22.6 U/L), with no growth on culture. CT Thorax showed evidence of granulomatous disease, and upon further inquiry, the patient recalled being treated for “pneumonia” in the past, but never for tuberculosis. Other imaging, including CT Abdomen/Pelvis and chest x-ray, and abdominal ultrasound were largely unremarkable. Tuberculosis IGRA assay was positive, and in the setting of an elevated ascitic ADA and findings on CT Thorax, RIPE therapy was empirically. Given his constellation of symptoms, paracentesis findings, but equivocal ascitic fluid ADA level, a peritoneal biopsy was obtained to confirm the diagnosis of peritoneal tuberculosis; however, pathological examination was negative for acid-fast bacilli. Instead, his peritoneal biopsy revealed the presence of Coccidioides immitis. Serum Cocci Ag titer was then obtained which was elevated (1:32). RIPE therapy was stopped and patient was started on high dose fluconazole, with plans to treat until a resolution of serum Cocci Ag titer, likely 3-6 months. Latent tuberculosis treatment was deferred to a later time.

Discussion: Coccidioides immitis is a fungus classically associated with the Southwestern US, though it is also found in parts of Central America. Infected patients are typically asymptomatic or have a self-limiting flu-like illness, but in rare cases the disease disseminates. The uncommon peritoneal disease is not well studied, but there is growing evidence for use of the well tolerated drug fluconazole for its successful treatment. The key to treating peritoneal Coccidioides thus is early definitive diagnosis. In this case, we were initially led astray by the patient’s latent TB and positive ADA, deciding to treat instead for the more common disseminated tuberculosis. This patient had few other clues that would have led us to the correct diagnosis – there was no eosinophilia and he was immunocompetent. A peritoneal biopsy was pursued to establish a definitive diagnosis, which ultimately led to the correct diagnosis and treatment.

Conclusions: This case illustrates the importance of biopsy and histologic examination in the diagnosis of low SAAG ascites. When peritoneal tuberculosis is considered in the differential, hospitalists must always consider and evaluate for other fungal etiologies as well, including Coccidioides, particularly if the patient comes from an endemic region. This is especially imperative in light of effective, well tolerated treatment for peritoneal Coccidioides.