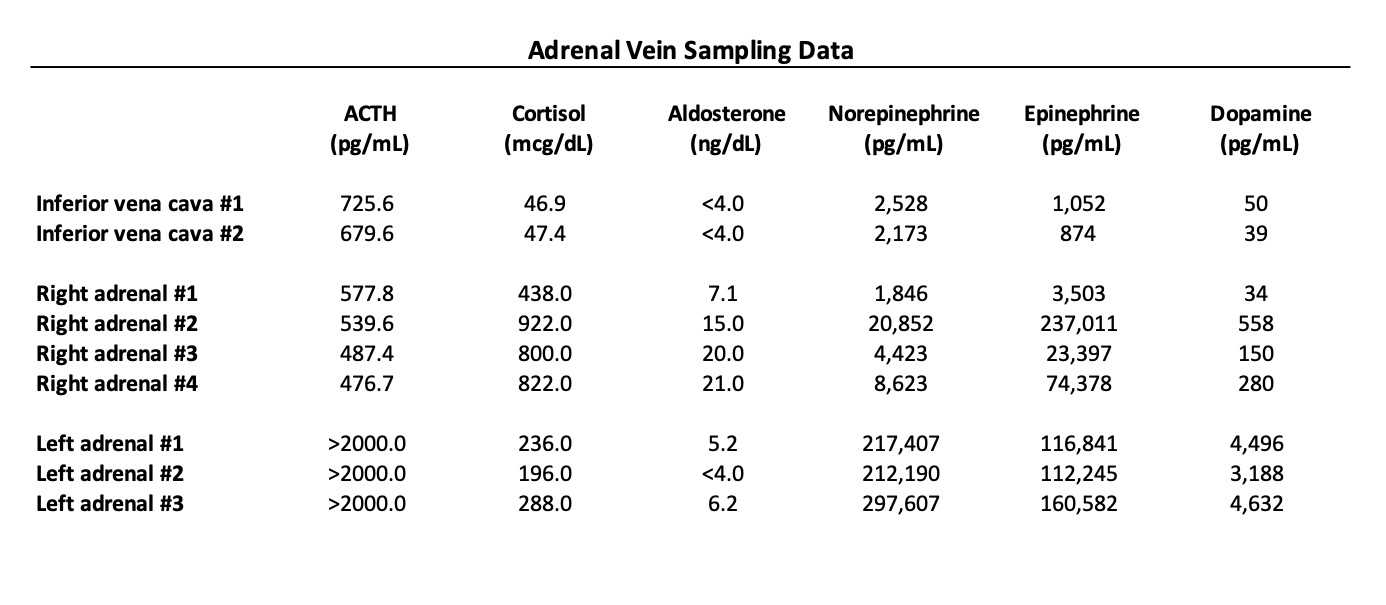

Case Presentation: A 62-year-old male with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, incidental left adrenal adenoma (3 cm), and resistant hypertension presented to the hospital with diffuse weakness, refractory hypokalemia, and hyperglycemia. Evaluation of his adrenal adenoma about a year prior had shown low serum aldosterone levels (in the setting of lisinopril use) and a normal 24-hour urine free cortisol. More recently, he had been admitted to other facilities for hypertensive urgency, hypokalemia, and hyperglycemia. The issues with hypokalemia had been ongoing for months despite supplementation and potassium-sparing diuretics. Given electrolyte abnormalities, hormone secretion of his adrenal adenoma was reassessed. Serum aldosterone was again low. Late night salivary cortisol and 24-hour urine free cortisol (6669 mcg/dL, range 3.5-45 mcg/dL) were newly elevated. Serum adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) was also elevated (682.9 pg/mL, range 7.0-63.0 pg/mL) consistent with an ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. Serum cortisol levels were not suppressed by low or high dose dexamethasone. An MRI pituitary showed a possible 4 mm microadenoma. Inferior petrosal sinus sampling was not concerning for ACTH overproduction by the pituitary. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed the known left adrenal adenoma but no other potential ectopic source of ACTH. Plasma fractionated metanephrines were also elevated to greater than two times the upper limit of normal. A literature review revealed case reports of ACTH-secreting pheochromocytomas. Interventional radiology performed bilateral adrenal vein sampling of ACTH, cortisol, aldosterone, and catecholamines that was consistent with ACTH hypersecretion by the left adrenal gland. The patient underwent a left adrenalectomy with pathology confirming a pheochromocytoma. Serum cortisol and ACTH and plasma metanephrine levels normalized post-operatively. The patient’s insulin requirements declined, his issues with hypokalemia resolved, and his weakness improved. He was weaned off of all anti-hypertensive medications.

Discussion: The presentation of Cushing’s syndrome is highly variable. In this case, high cortisol levels presented as a steroid-induced myopathy and an excess mineralocorticoid activity state that resulted in a prolonged hospitalization. In the evaluation of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, the source of ACTH is most commonly outside of the adrenal gland (e.g. the pituitary or malignant tumor). This case illustrates a rarer ectopic source of ACTH production – pheochromocytomas. Interestingly, this patient’s high cortisol levels and associated Cushing’s syndrome were not present at the time of initial recognition of the left adrenal adenoma. Prior case reports of ACTH-secreting pheochromocytomas present immunohistochemical and in vitro evidence of a positive feedback loop involving glucocorticoid-induced ACTH secretion, which may explain why this patient developed progressive hypercortisolism with time.

Conclusions: Adrenal tumors are a relatively common incidental imaging finding. Practitioners should have a low threshold to repeat testing for hormone secretion of these tumors as it can evolve over time. Recognizing hormonal syndromes and understanding diagnostic algorithms associated with hormone-secreting adrenal tumors are important skills for hospitalists as resection of these tumors is associated with significant reduction in morbidity and improved quality of life.